How the Budget can help India's nascent space tech startups

Beyond tax cuts and incentives, the government could support private enterprises in the sector by becoming a bigger consumer of new space solutions

India’s Department of Space’s budget for the current fiscal year, as proposed in the interim Budget presented in February, is Rs 13,042.75 crore. On July 23, we’ll get to know the new government’s revisions, if any, for the year that ends March 31, 2025. The current figure compares with Rs 12,543.91 crore for FY23 and Rs 10,139.43 crore for FY22, according to the space department’s notes on grants for the current fiscal year.

In recent years, these budgets have seen modest, incremental increases, even as the Government of India has taken important steps to open the sector to private enterprise. Experts say that Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro), the space department’s main constituent that carries out the national space programme, should be getting significantly more money, given its outstanding achievements with frugal resources.

And, as a proportion of national GDP, India spends much less on space exploration than most other major space-faring economies, they point out. For example, reflecting the difference in the size of the two economies, plus higher spending, China has roughly 10X more active satellites in orbit today, and launches about 10 times more than India.

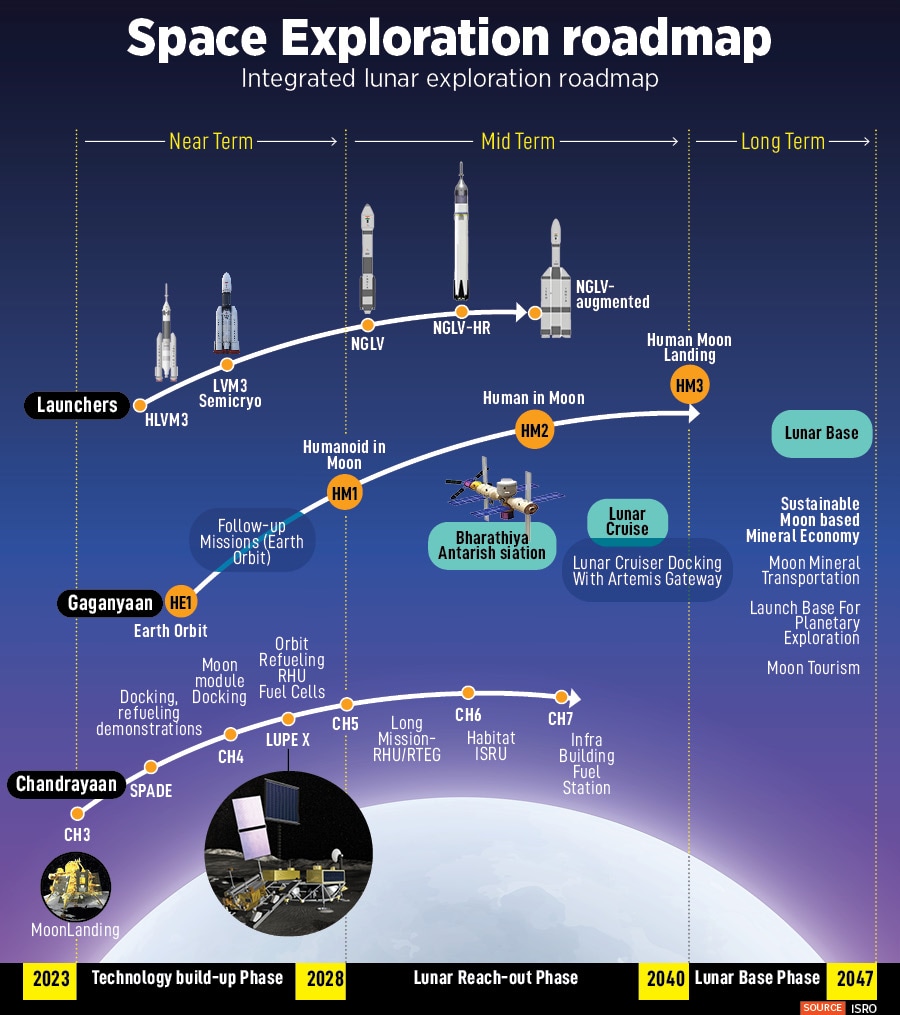

If one anticipates the day when India’s economy is twice as big as it is today, and in tandem “if we increase Isro’s budget and get to double it, then we may end up doing a lot more missions than what we do today," Narayan Prasad, co-founder of Satsearch, a space-tech marketplace, and co-founder of Spaceport Sarabhai, a Delhi-based think tank had told Forbes India in an interview, after India joined the US-led Artemis Accords last year. These accords are a series of non-binding multilateral agreements to return humans to the Moon by 2025, and eventually going to Mars and beyond.

In addition to boosting its international standing in space exploration, India also has established the institutional infrastructure and policies to foster private investment in the sector. The Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) is tasked with expanding the commercialisation of India’s space tech capabilities.

In April last year, the government also released India’s space policy, to promote a comprehensive approach to the space economy opportunity ahead. In February this year, it amended foreign direct investment (FDI) rules to allow as much as 100 percent investments via automatic route in certain categories such as satellite subsystem and components manufacturing.

The government’s estimate projects India’s space market to be worth $40 billion in 2030. This could go as high as $100 billion, the consultancy Arthur D Little says, if investments and efforts in certain focus areas are stepped up.

Indian space tech startups have gone from raising only $35 million in funding between 2010 and 2019, to $28 million in 2020 to $96 million in 2021 and $112 million in 2022, according to Tracxn, a private markets intelligence provider. Even though the venture capital (VC) funding landscape shrank last year, the sector in India attracted $62 million in funding as of August 2023. They are developing a range of technologies and products, including hyperspectral imaging, 3D-printed rocket engines, satellite propulsion systems and sustainable green rocket fuels.

Today there are several Indian space startups that are looking for growth capital of as much as $50 million each, having demonstrated the provenance of their technologies. “We are trying to expand globally, and we are in search of new capital," says Rohan Ganapathy, co-founder and CEO at Bellatrix Aerospace in Bengaluru. “Considering the global scenario, getting capital today is a little bit trickier." He is hopeful of raising the new investment by the end of this year, as Bellatrix looks to build a state-of-the-art, vertically integrated manufacturing facility for its satellite propulsion systems.

With the development of a nascent private space-tech ecosystem in India, there are two perspectives on future funding in the sector. First, of course Isro should get more money, because in the foreseeable future, it will continue to execute all of India’s national space missions by itself and occasionally use launch and services and other tech from the advanced providers in the US and Europe.

And India’s private space-tech ecosystem owes its very existence to Isro, says Rajan Anandan, managing director at VC firm Peak XV Partners. “Isro is the reason we have a space tech sector. For a long period of time, for many decades, you had talent that was trained at Isro, you had world-class, affordable infrastructure, launch technologies that were developed there. So, without Isro, we wouldn"t have a space tech sector," he points out. “But I think what has changed is deregulation," which allowed new space-tech startups to come up in India. The founders of Skyroot Aerospace, for example, are former Isro scientists and engineers. They are building space launch vehicles.

Ganapathy, at Bellatrix, echoes this sentiment. “First, let us take the simple route. We hope they increase the budget of Isro so that the industry gets benefited," he says. However, going forward, “Isro as an organisation has its own goals. They have the national missions, which they have to first deliver." Now, with the opportunity to foster a global private industry in space tech in India, the government should continue to support the growth of space-tech startups, he says.

Today, there is also an overlap between the broader deep tech ecosystem in the country and the space sector he says. In this context, the government should also encourage institutional investors such as the Small Industries Development Bank of India (Sidbi) and other government-led fund of funds to become limited partners in VC firms, he says.

And there is need for a multi-disciplinary approach to policy making. For example, “now we are talking about certain cancer-curing drugs that can be brewed in microgravity conditions, some antibiotic strains which grow better in microgravity conditions." But the health care regulations in the country don"t allow this, he says.

Another related, and critical factor is manufacturing of specific components and sub-systems that go into satellites and other systems currently this is absent in India and startups such as Bellatrix have no option but to either import the components they need or develop and make the devices themselves. Therefore, one specific move could be to lower the tariff imposed on the importation of such components.

From a financial perspective, reductions in taxes across space-tech activities, including more support for ‘greenfield’ projects, and a dedicated production-linked incentive (PLI) plan for manufacture of space-grade components will help the sector, Deloitte, a multinational accounting firm and consultancy, said in a recent note on budget expectations.

Deloitte also echoes a sentiment prevalent across tech startups in India. If the government itself became a bigger consumer of the “new space" solutions coming out of India’s space startups, that would also significantly boost the private space sector in the country.

First Published: Jul 18, 2024, 14:40

Subscribe Now