How the coding craze, led by WhiteHat Jr, lost its magic

Kids are back to school, and parents are getting disenchanted with this expensive extracurricular activity, which they once thought was the X-factor that would help their children shine

It was an immensely proud moment for Gunjan Kar. And why wouldn’t it be? Last year, the marketing professional at an advertising agency in Gurugram got a congratulatory mail from coding startup WhiteHat Jr, which narrated the achievement of her 14-year-old son. “We are delighted to share that your son is now one of the youngest kids in the world to become a certified android developer," underlined the mail from the startup, which was bought by Byju’s for $300 million in August 2020. For a startup that was just a little under two-years-old and had raised $11 million in venture capital, being valued at Rs2,250 crore by Byju’s, India’s largest edtech company, was staggering.

For Kar, too, it was overwhelming. At such a young age, her son had emerged as one of the youngest creators of mobile applications—he had built a mobile game—and had received an official WhiteHat Jr android developer certificate. The letter also asked Kar to share a picture of her son holding the certificate with the hashtag #WhiteHatJr in order to get featured in their community and to ‘make a mark among our millions of followers’.

The same year in Mumbai, Snehanshu Mandal enrolled his 10-year-old daughter in a coding course. A software consultant for over two decades, he had related to the benefits of coding that was propounded by WhiteHat Jr in one of its advertisements. Coding, the startup stressed in its sanitised site after expunging the preposterous claims of coding that it had carried for long, will help your child learn logic, structure, creative thinking, sequencing, and algorithmic thinking. Mandal was in sync, and bought a course for his daughter.

In Bengaluru in 2021, Neha Gupta enrolled her daughter Advika into WhiteHat Jr. Most of her daughter’s friends had signed up, and she had wanted to join too. Thought reluctant, a demo session convinced Gupta that Advika, who is 8.5 years old, had an appetite for coding.

In Bengaluru in 2021, Neha Gupta enrolled her daughter Advika into WhiteHat Jr. Most of her daughter’s friends had signed up, and she had wanted to join too. Thought reluctant, a demo session convinced Gupta that Advika, who is 8.5 years old, had an appetite for coding.

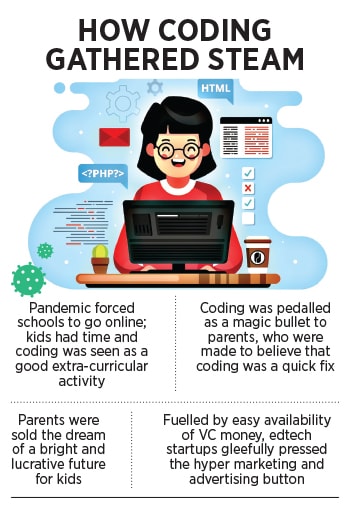

What had fanned the demand for coding, which started to swell in the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, was a combination of a few factors. First was the promise of a bright future made by most coding startups. This promise was built on the foundation of FOMO (fear of missing out). Coding was pedalled as the next big thing to happen in India. The funding boom and news of edtech unicorns was already grabbing the attention of everyone inside and outside the startup world and insecure parents were desperate to find a secure future for their kids. The imagery created by coding startups—from ‘the next billion-dollar idea can come from your kids’ to ‘Silicon Valley is waiting for the tech geniuses’ to ‘make your child a TedX speaker’ or ‘an app developer’—got the parents hooked.

The second factor that led to more kids—as young as four and five years old—take up coding was the pandemic. Schools went online, extra-curricular activities and outdoor games came to a screeching stop, and coding was born to fill the gap. Though most of the courses were expensive–Kar spent over Rs 70,000 in a year or so—it didn’t bother parents who started displaying a herd mentality. Coding was seen as an X-factor that would equip kids to shine in life.

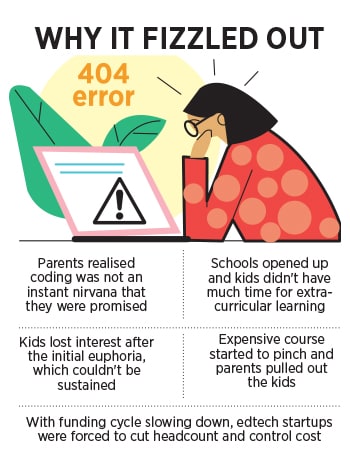

Fast forward to July 2022. A lot has changed over the last few months. Let’s start with coding consumers. Kar’s son doesn’t know what to do after making a ‘mobile gaming app.’ Now, in class 10, he has quit coding. “He has lost all interest," Kar says. There was not enough blueprint for his future. In one of the TV advertisements by WhiteHat Jr in 2020, which drew massive flak and ridicule on social media, a boy was shown making an app and investors are fighting outside his home to buy his revolutionary idea. Though Kar never got influenced by the commercial, now she knows the ‘commercial’ side and the ‘reality’ of coding. “My son did learn something, but it’s definitely nothing compared to what he learnt at his school," she reckons. After a year of coding classes, she underlines, there was a strong need of missing out (NOMO).

Mandal narrates a similar story. "Lack of basics and copycat coding killed the kid"s creative approach towards problem solving," rues the 49-year-old father. He explains what went wrong. Coding startups, according to him, served instant food, which parents did not realise were devoid of vegetables and nutrition. “There was no real learning," he says. To show gratification in the shortest possible time, tutors skipped the basics, and kids made some apps mostly with tutored steps from teachers. “Kids didn’t solve any problem. They just replicated certain steps," Mandal says.

Gupta in Bengaluru is also a disillusioned mother. After eight sessions, her kid lost interest. Gupta puts the blame on the format and the manner in which coding was taught. As a new activity, kids got interested but an increase in familiarity with the subject and the speed of teaching killed the interest. “It fizzled out after sometime," she says.

Gupta, Mandal and Kar are not the only parents to pull their kids out of coding classes. Forbes India spoke with over dozens of parents over the last two weeks. It’s the same story of misleading promises of a lucrative future turning into ugly reality that there is no short cut to learning, fame and success. And the final nail in the coffin is the re-opening of schools, which has killed the ‘extra’ that coding offered.

The new reality also gets reflected in the way edtech startups have been behaving. Recently, WhiteHat Jr laid off close to 300 employees, and in a recent interview to Forbes India, Byju Raveendran, founder of Byju"s, maintained that WhiteHat Jr is now more focused on overseas market. While revenue from operations jumped to Rs483.9 crore in FY21 from Rs19 crore in FY20, the losses leapfrogged to Rs1,690.5 crore from Rs48.95 crore during the same period.

The new reality also gets reflected in the way edtech startups have been behaving. Recently, WhiteHat Jr laid off close to 300 employees, and in a recent interview to Forbes India, Byju Raveendran, founder of Byju"s, maintained that WhiteHat Jr is now more focused on overseas market. While revenue from operations jumped to Rs483.9 crore in FY21 from Rs19 crore in FY20, the losses leapfrogged to Rs1,690.5 crore from Rs48.95 crore during the same period.

Byju’s, however, is upbeat about its operations and plays down the layoffs. "In order to reduce redundancies across our organisation after multiple acquisitions, we had to let go of nearly one percent of our 50,000+ strong workforce, which included less than 300 people from WhiteHat Jr," says a Byju’s spokesperson in an email reply. The coding segment, the spokesperson underlines, continues to remain bullish across geographies, including India. “Over the last two years, we have successfully introduced courses in other disciplines such as math, music and art," the spokesperson adds. In short, WhiteHat Jr has been diversifying by offering more courses in diverse streams.

The move, though, doesn’t find many takers. “You started with coding. You identified yourself as coding and now you are teaching maths, music and arts," says an edtech founder requesting anonymity. “It’s like Haldiram’s offering Chinese and South Indian cuisine as well." The move, however, the founder explains, makes sense for the startup. With coding for kids losing steam in India, they would need to add more subjects.

Avneet Makkar, a former Infosys engineer, concedes that while coding is an essential skill for kids to learn, the issue was with the way startups designed their products and curriculum. “The objective was wrong," says the edtech entrepreneur, who co-founded CarveNiche in 2010, and AI-based math learning programme beGalileo in 2016. “It was more about what students can do that parents can showcase to others and feel proud about," she reckons. In education, unless students and acquisition of knowledge are kept as primary objective, results can’t be delivered. “Education cannot be sold as a commodity," she says.

Image: Arpit Jain for Forbes India

Image: Arpit Jain for Forbes India

Explosion of social media also did its share of damage. Many edtech companies, Makkar sayss, designed curriculum where kids gained very little knowledge but were able to show [that they developed] an app or a game, which parents were more than happy to share. It yielded good results for some time, but every trend has a shelf life and such demand cannot be sustained because the audience would always need new things to showcase.

Over the last few years, Makkar has focused on global markets at the cost of domestic play. She explains why the Indian edtech market had little juice for players like her. “We would have got lost in the marketing hype of players with huge ad spends," she says. It was prudent, she adds, to focus on markets where we she could talk about results, outcomes, superior product and deliver value to customers, rather than fight out for low margins by targeting the customers who are already tired of seeing so many edtech products. Commenting on how a bunch of edtech startups are closing down—all putting the blame on opening up of schools—Makkar reckons that the startups should have done some introspection. “They never gave themselves time to even see if their product worked, and did the students got what they were looking for when they signed up?" she says.

Saumya Yadav, who shut down her edtech startup Udayy early this year, says that demand for faster outcomes, high course costs and the inability to keep the course interesting for a long period of time, and the children losing interest combined to the demand in the coding industry. “False advertising by some companies further increased parent expectations about outcomes," she says. A limited market in India to pay for a high-priced one-on-one class also played a role. “The target market is already limited for this model," she says, adding that though short curriculums are good for introducing coding, they need to be supplemented with a longer duration study for tangible outcomes. “Let’s get this right. Coding is here to stay. It’s a long term thing," she underlines.

Meanwhile in Gurugram, Kar feels sorry for parents and kids who got singed by reckless coding fire. To a large extent, it was a pandemic baby. The greed and haste of edtech companies, though, made it an unwanted child. Parents too, Kar says, are to be blamed. “Kids are growing on instant food and parents want instant results," she says. Over the last two years, coding had been what the doctor ordered. But the doctor also always emphasises chewing over swallowing food. “Coding is a long-term thing. It has to be chewed," she adds.

But can the edtech startups, now looking for instant ways to survive a funding freeze, change their way of life? And can parents, who now seem to be disenchanted with coding, think beyond magical nirvana solutions for their kids? The picture will get decoded over the next few years.

First Published: Jul 11, 2022, 16:39

Subscribe Now