Inside Sanjay Mehta's ambition to build India's Y Combinator at 100X.VC

Entrepreneur-turned-investor Mehta is making life easier for early-stage startups, helping them to focus on their ideas, while handholding them to raise money

Image: Mexy Xavier

Image: Mexy Xavier

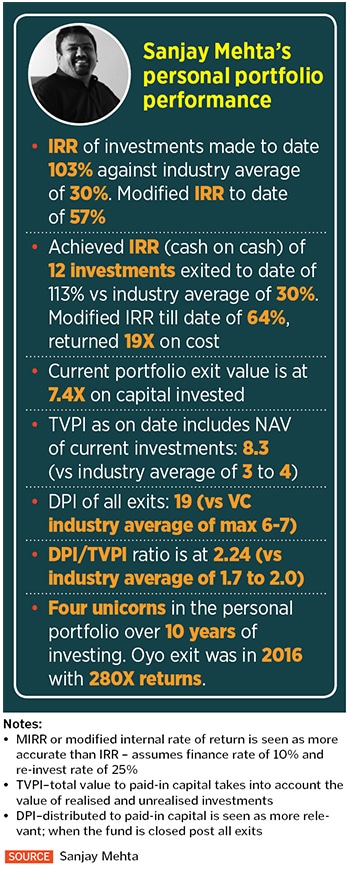

A spectacular 280x exit from Oyo Rooms in 2016 made Sanjay Mehta a celebrity in India’s venture capital circles. It hasn’t been a one-off either, even though Mehta is the first to insist that no one can predict these things. Other notable deals he made include a partial exit at Block.One, a blockchain company backed by Peter Thiel, Silicon Valley billionaire co-founder of PayPal, and, more recently, Indian logistics intelligence startup Loginext, where Mehta got a 16x return.

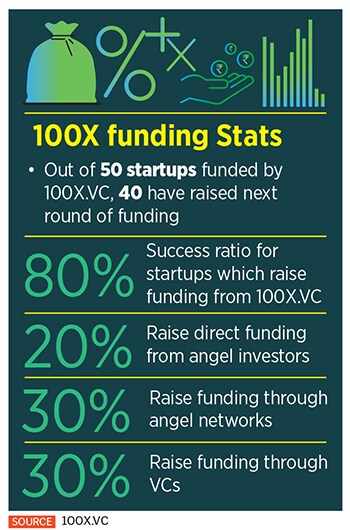

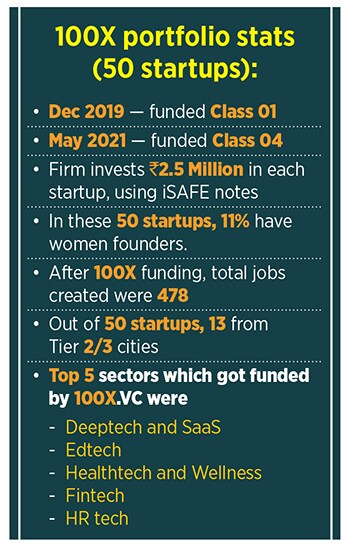

While Mehta (50) has invested his personal wealth in over a hundred startups through his family office, Mehta Ventures, his most interesting innings might have started only two years ago. In December 2019, 100X.VC, which Mehta started with like-minded partners, took in its first ‘class’ of startups—20 of them. Today Class 05 is open, and the first four classes add up to a portfolio of 50 startups.

“The mission is to invest in a 100 startups every year," says Mehta in an interview with Forbes India. And the idea behind that is to showcase startups by committing his own money to them, he says. This brings both visibility and credibility to those startups, which helps them in raising larger, subsequent rounds of funding as they grow.

“The mission is to invest in a 100 startups every year," says Mehta in an interview with Forbes India. And the idea behind that is to showcase startups by committing his own money to them, he says. This brings both visibility and credibility to those startups, which helps them in raising larger, subsequent rounds of funding as they grow.

Eventually 100X will become a place where other investors and investment firms looking to fund promising startups can discover such ventures, Shashank Randev, founder VC at the firm says. Other prominent colleagues of Mehta include Ninad Karpe, partner Yagnesh Sanghrajka, founder and CFO and Vatsal Kanakiya, a computer science engineer, who is CTO and also happens to be Mehta’s nephew.

Karpe was previously CEO and MD at computer education company Aptech. Randev was the founding member and vice president at financial research platform VC Circle Edge, and Sanghrajka has been an investor, advisor and mentor at multiple companies.

Over the last 10 years, Mehta has had a ringside view of the challenges India’s nascent startup ecosystem faces. One problem in particular was the time it took for a startup to get money in the bank even when investors had reached an agreement to fund the venture.

To Mehta, who had also invested in Silicon Valley startups, this contrast was stark. “The time it took for deal closures was a big pain in India," he says. “Typically, a term sheet to money in the bank would take three to four months. That was crazy."

Second, most of the deals at the angel funding stage were being marketed. Meaning, “there was no skin in the game … they were just peddling deals". Then there were all kinds of ways in which others were sucking away precious money from the founders, in the name of deal sourcing, investment banking fees and so on.

Mehta wanted to build a transparent platform that took on some of the risk—investing Rs 2.5 million as the first investment in each of the 100 startups every year. He also wanted to eliminate the friction in the process of fundraising, especially for early-stage startups, when founders often had little more than an idea, making things like valuation tricky.

On the funding front, Mehta decided to take a cookie-cutter approach and simplify the seed funding process. It became a motto: “Funding simplified". And then, 100X became the “social proof" for its portfolio companies. Both the VC firm and the startups could say they already have skin in the game in approaching other investors. Then it isn’t shallow marketing anymore, but a proclamation that “we believe in this startup and in these founders", he says.

The next stage was about helping the startups get off the ground and grow. This became the “mentoring unlimited" motto of the firm. From the time a startup becomes a portfolio company of the VC firm, there is continuous engagement between the two on various aspects beyond funding raising—from hiring the right recruits to pricing products, developing the right business models also supporting founders who’ve reached the point where they know they have to make course corrections or even drastically change their business models—a process popularly called ‘pivoting’ in startup parlance.

iSAFE notes

To give simplified funding a formal structure, Mehta created a simple document not very different from a convertible note, called the iSAFE note, an abbreviation for India simple agreement for future equity. The advantage is it doesn’t reflect a debt on the books of the startup, so if the venture doesn’t work out, there’s no loan to pay back, Mehta says.

Second, the VC firm doesn’t decide on a valuation of the company right away, but typically invests about Rs 2.5 million in each portfolio company to start with, securing a right for some future equity whenever the startups do subsequent pricing rounds of funding.

This simplifies the transaction significantly, and also enables bringing on other angel investors as and when they are ready. A conventional shareholder agreement that multiple investors agree on would require getting them all on to the ‘cap table’ of the startup by signing on to that one agreement. The iSAFE note, on the other hand, allows angel investors to strike one-on-one deals with the startup, so the founders can focus on starting work sooner.

Therefore, investors who are ready can jump in and others can take more time, Mehta says, making it an everybody-wins process. Further, with the rights secured for equity in a future pricing round, it also saves investors from at least one round of valuation-driven dilution of their stake.

Team 100X: (from left) Vatsal Kanakia, Yagnesh Sanghrajka, Shashank Randev, Sanjay Mehta, Ninad Karpe

Team 100X: (from left) Vatsal Kanakia, Yagnesh Sanghrajka, Shashank Randev, Sanjay Mehta, Ninad Karpe

It also does away with a host of other potential burdens like board seats, the need to set aside an Esop pool or agreeing to provide investors a certain rate of return and other such “stupid clauses" he says. “In early stage, you need to focus on nurturing the idea and the startup," he says.

Mehta also open-sourced the iSAFE document, meaning anyone can download and use it as a template for striking an investment deal with a startup. “It has been a boon to many startups," he says. In the absence of such notes, Mehta says he has come across ventures where the founders ended up losing as much as 10 percent of their funding to legal and other fees.

The iSAFE note is about five to six pages and a typical shareholder agreement can easily run into 60 or more. 100X has a primer on these notes on its website and the idea is to make this simple enough for founders, without financial jargon.

Kinner Sacchdev, co-founder and CEO of Knorish, recalls meeting Mehta at the speakers lounge at an event organised by The Indus Entrepreneurs, a network of entrepreneurs, in 2019. Knorish is a do-it-yourself platform for creators to take their talent online and monetise it. Sacchdev sent Mehta a pitch deck the same day and was invited to Mumbai to meet others at 100X. “Within a week, we had the money." Says Sacchdev, who became part of the firm’s Class 01.

“I had heard about 100X with their Y Combinator style model. I just sent them a cold email with my pitch deck and no introductions," Snigdha Kumar, a former Flipkart executive, who is now CEO of her own startup, Cora Health, tells Forbes India. 100X invested in her startup last December.

These notes were first introduced in late 2013 by Y Combinator, the famous Silicon Valley venture capital firm, for companies in the US. Since then, other firms have used them too. Indian startups compete to be on Y Combinator’s annual batches, and notable alumni include fintech company Razorpay and social commerce startup Meesho.

Mehta’s iSAFE notes are customised to Indian rules. And like Y Combinator, 100X has now been doing two batches a year.

Entrepreneur first

“I was always an entrepreneur. Even today I’m more of an entrepreneur than an investor," Mehta says. “I love to get my hands dirty and that’s where I enjoy my work. I’ve been through these journeys myself." He started with a bespoke software company Globalware Systems and Solutions around 1993. It didn’t scale, he told CampdenFB in December 2019. A couple of dotcom failures followed and took a big chunk of his personal wealth.

“Those were tough times, I had difficulties meeting salaries, and it was the rollercoaster ride of an entrepreneur," he says. “I’d manage by figuring out my zero-cash dates—one of the most important things I learnt in the early 2000s."

Then followed two good exits of companies he built. Udyog Software India, which became the largest selling excise software company in packaged software in India, was bought by US-based Adeaquare. Mehta then started business software and analytics company MAIA Intelligence, which was bought by Datamatics in 2015.

“Yes, I made money on those exits but they were not the kind of thumping exits you see today in the news," Mehta says.

The switch to venture investing happened by accident, he says. Harish Mehta, one of the founders of Nasscom and chairman of Onward Technologies roped in Sanjay—who was on Nasscom’s regional council in Mumbai—to help him with developing the Indian Angel Network. “He brought me into investing."

Sanjay Mehta started out as a limited partner in private equity funds such as the Aditya Birla PE fund. As a tech-oriented entrepreneur, he saw a lot of deals in 2010-11 in Mumbai, as many financial investors saw him as the go-to person on tech startup deals.

“It grew on me," he says. “When you have experienced that yourself, you can empathise with the founders." The process is a big high because it gives one a chance to foster many ideas, he says. “My day is made when I hear a great idea and I’m able to invest in it. And founders’ enthusiasm is contagious—when you meet good founders, you are inspired by them."

That way, “I’m fortunate to have four unicorns in the portfolio, including one that is yet to be announced." These are from his Mehta Ventures investments and include Oyo and Block.One. In May 2019, Block.One gave returns of 6,567 percent to investors including Mehta, via a sale. Block.One has now launched a crypto exchange called Bullish that is “capitalised with almost $10 billion … crazy stuff, so holding onto that, big one."

Then there is the ex-NASA engineers-founded Axiom Space, which is building a commercial space station. “I get my adrenaline rush meeting all these founders and I get financial returns, what better work can you think of," says Mehta.

But he is the first to insist that he never could have predicted the successes. “The way I see it, did I really know that Oyo would become what it is? No, I didn’t. Otherwise, I would have put all my money over there," he says. “But that’s how venture investing is like. You work with every founder and time will tell who will become a unicorn and where you’ll get an exit."

In fact, there are Mehta’s investees, whose first ideas didn’t pan out as expected. Block.one is one such company, where the founders had a different idea the first time, but they had to shut it down. But Mehta continued to invest in them. The idea here is that VCs bet on founders in the early stage, more than anything else.

Sector agnostic

In addition to a 50-60 percent weightage going to the founding team, other factors that are considered in an investment include the size of the market opportunity, how rapidly the startup can grow, the business model do they have a path to profitability and what is the intellectual property and the unfair advantage the startup might have.

Last, an internal check within 100X is to ask the question ‘does this idea have the possibility of a 20x exit?’

There can be great businesses that are tough to exit, Mehta says. Therefore, 100X looks at moon shots that can redefine a market. For example, in the fourth cohort, the firm invested in a company called Kroop AI that detects deep fakes, which are now growing at an alarming rate. Another example is Talkie, which is developing a voice-only collaboration tool.

Other examples are in the area of authentication, converting content into regional language, women’s health, vernacular coding and a company that has developed a micro-dialysis machine, a boon during Covid times, Mehta says.

All these companies—each in a different field—have one thing in common. They all have a large market opportunity. In this way, 100X.VC is a sector-agnostic fund, he says.

And true to that philosophy, the firm has invested in everything, from a banana chips venture from Kerala to robotics and drone companies. Two emerging areas that hold a lot of promise—accelerated by the Covid pandemic—are future of work and the home economy, and investors are scouting for startups in these areas, he says. Then there is crypto-currency, which could be a huge opportunity for India. “We’ll see many crypto billionaires in India soon," he says.

In any investment, the trick is to pick the problem first, to identify if what the founders aim to solve represents a substantial opportunity. In other words, he may not invest in an AI company for the sake of the technology, but only if that particular application of AI is likely to solve an important problem for a large number of customers.

“Many times, startups can build something that no one wants, which are recipes for failures," he says.

Founder friendly

That said, “they are very founder-friendly, they have a lot of patience with us as we take our first steps", Kumar at Cora Health says. When Kumar met 100X.VC she had finished three pilots to test her idea but had not opened for business, “so a lot of what we were talking about was still only on paper". But the VC firm took the time and made the effort to validate what she was telling them.

That said, “they are very founder-friendly, they have a lot of patience with us as we take our first steps", Kumar at Cora Health says. When Kumar met 100X.VC she had finished three pilots to test her idea but had not opened for business, “so a lot of what we were talking about was still only on paper". But the VC firm took the time and made the effort to validate what she was telling them.

“They have been super helpful with everything," Sacchdev at Knorish says, and he has gone on to raise subsequent rounds of funding. The brainstorming and mentoring sessions that 100X.VC organises for its portfolio companies are super useful he says. For example, in addition to the session itself, he met a future investor in one of those meetings. Uday Sodhi, formerly a senior executive at SonyLIV, and who now runs his own digital transformation agency, joined a subsequent round of funding at Knorish.

While 100X’s first cheque of Rs 2.5 million is a small one, it’s really the downstream impact of the firm’s backing that founders value. “To be honest, the capital infusion per se is the least helpful thing they did for us, compared to many other areas where they added value," says Omkar Pandharkame, co-founder and CEO of BHyve. “I’m not sure if it’s fair or right to call them this, but they are pretty much the Indian version of Y Combinator."

“After being selected by 100X, we went to a demo day and we closed a round of Rs 20 million in just eight days. The speed at which they operate is a big benefactor to the Indian startup ecosystem," says Pandharkame. “There were two meetings, one negotiation, one term sheet, and money in the bank in less than a week."

Sacchdev adds: “I have friends who have superb products, but have been struggling to get their first investors." It seems that one of the biggest challenges for startups in India even today is to be discovered by the large funds or angels. “You can’t cold mail them and expect replies. I’d actually tried that before meeting 100X. The first trust that they build by investing a small cheque, goes a very long way."

100X works on both supply and demand of startups and funding, Kumar says. On the one hand, they work with a large number of startups, and, on the other, they provide a launchpad for their portfolio companies to get funded in future through their angel networks and VC funds that they can put the startups in touch with.

Sacchdev found his first celebrity clients through 100X’s network. And the firm also helped with important recruitments. Pandharkame echoes this. Because BHyve got introductions to some clients through the 100X.VC network, “it became easier to get face time with the decision-makers without having to win over gatekeepers", he says.

Then there is a lot of information in the startup industry—experience from those founders who have made it big, which can help new founders, Kumar says. And Gurukul, 100X’s online education portal for aspiring entrepreneurs, is about consolidating and sharpening the focus of this knowledge sharing effort, she says.

Needed, more domestic capital

Much has changed in India since he first started investing in startups, Mehta says. “Today founders are well educated, they have skin in the game, they know exactly what they want and the ecosystem has grown a lot." And the government has helped significantly with various programmes like the Atal Innovation Centres, encouraging colleges to start incubation centres.

Today, a growing share of the startup founders in India comprises those under 25, he says. Then the best place to encourage entrepreneurship is the college. Now, the government’s programmes are taking entrepreneurship to the grassroots. We are on the cusp of a significant change in India’s startup ecosystem and the 100 unicorns dream by 2025 will be realised before that, he says.

The latest edition of an annual ‘sentiment survey’ that 100X does, bears out this optimism, he says.

On the other hand, unicorns are being created the world over at least in a significant part because of cheap money from the US. What will really change India’s startup landscape is if more local investors and domestic capital gets involved.

Even today, the valuations and outcomes are being driven by companies like SoftBank and Tiger Global, he says. “What we need is more of Tata acquiring BigBasket rather than Walmart acquiring Flipkart. That’s the truth of it. Walmart really gave a jolt to a lot of Indian corporates when Flipkart got acquired. It was like a jewel going away."

Corporate venture capital in India has to open up more. Once domestic investors taste success with startups, a lot of things will change. If the top 200 established corporate businesses in India allocate Rs 500 million a year to startups at the seed stage, they will change the landscape, he says.

“And they have enough cash on their balance sheets to easily do this," and they will see the benefits to their own businesses too.

Today, be it search engines or social networks, Indian users are dependent on Google, Facebook and others and there is nothing that is owned in India, Mehta says. And while there are many Indian unicorns today, none comes even remotely close to dominating its particular market segment even locally, let alone becoming a global story. Over the next three to five years, he hopes there will be some local successes too.

Catch our recent Startup Fridays conversation with Sanjay Mehta here:

First Published: Jul 07, 2021, 14:31

Subscribe Now