Obesity, Fat Boy, and the Lost Brotherhood

The untold story of how iconic American bike maker Harley-Davidson lost its H-D vision in India

Harley Davidson 750 Street Road Motorbike exhibited at a fair. Image: Shutterstock

On June 29, Sajeev Rajasekharan hogged the limelight. The managing director (Asia emerging markets and India) of Harley-Davidson sounded euphoric, and with good reason to.

In a first for India, the iconic American bike maker live-streamed a virtual Eastern H.O.G. (Harley Owners Group) rally on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. One of Harley-Davidson’s zonal rallies—originally slated for March but pushed back due to the lockdown—the show grabbed eyeballs: over 5.7 lakh organic viewers from the H.O.G. community, a riding club of Harley users started in India in 2010. Globally, H.O.G reportedly has close to 1 million members in 140 countries.

Back in India, the live virtual rally was a moment of pride. “With these changing times,” underlined a beaming Rajasekharan in his virtual welcome message, “Harley-Davidson India is adapting to new ways to provide experiences to its riders and deliver upon the promise of a Harley lifestyle.”

The H.O.G. community, which was thrilled to see a high-decibel performance by leading artists such as Ash Chandler and Rahul Ram from the band Indian Ocean, also witnessed the first virtual launch of H-D’s new Low Rider S model, a cruiser priced at Rs 14.69 lakh. “This virtual rally,” the top honcho of H-D said with pride, “is a testament of our commitment towards celebrating the H.O.G. community.” The intent of keeping riders at the forefront, and a high definition vision for the Indian market, was clearly visible.

Three months later, on September 24, Rajeev Kumar, one of the H-D riders in Mumbai, felt betrayed. Kumar, a businessman who bought a Low Rider last year for Rs 18.5 lakh, was unaware of H-D’s exit from India. In a media release, the company said that it is closing its manufacturing facility in Bawal in Haryana, and significantly reducing the size of its sales office in Gurugram, the Indian headquarters for the Wisconsin-based makers of cruiser Fat Boy.

“The company is communicating with its customers in India,” the release added, saying that riders would be kept updated on future support. ‘The company is changing its business model in India, and is part of the Rewire, a new strategic plan for the global US bikemaker,’ it added.

Kumar, though, is not amused. “It’s shocking. Nobody informed me,” he says. The brotherhood, a term for close-knit Harley riders, were caught unawares too. In fact, for Kumar, it was a sense of déjà vu. In May 2017, General Motors had decided to pull out of India. Chevrolet Captiva, a compact crossover SUV that Kumar bought for over Rs 25 lakh in 2016, suddenly lost its resale value. Stressed, Kumar pressed the panic button and went for distress sale: a paltry Rs 4 lakh. “Now what will I get for my Low Rider?” he asks, looking dejected over a Zoom call. “I feel cheated. What brotherhood do they talk about? It’s all hogwash,” he fumes.

Meanwhile in Gurugram, some 65 kilometres from Bawal, Bhaskar Basu is ‘utterly disappointed’. In January this year, the director (strategic partnerships) at Microsoft India had bought his second H-D bike: a Softail Low Rider for under Rs 15 lakh. Basu’s tryst with H-D began in 2017 with an Iron 883. H-D’s exit now hit him on two fronts.

The first is emotional. “I love the brand. It’s a privilege and pride to own it,” he says, adding that his brother too owns an H-D. As Harley-Davidson makes it way out of the country, Basu reckons an emotional part of his life too would cease to exist. The second setback is the practical one on the operational front. “What happens to all H-D bikes in India now?How would they get serviced? Where would I get spare parts from?” he questions. “The future is uncertain.”

Gurugram-based Bhaskar Basu, a Microsoft executive, is "utterly disappointed" at Harley"s exit.

Gurugram-based Bhaskar Basu, a Microsoft executive, is "utterly disappointed" at Harley"s exit.

Cut to Lucknow, where H-D opened a store in 2015. “Not informing bikers is okay. But keeping partners in the dark is a breach of trust,” says a dealer, requesting anonymity. “What happens to all the money that I put into the venture? Nobody has contacted me so far,” he says.

Harley-Davidson didn’t reply to a set of questions sent by Forbes India. “At this stage, the press release is the only information we have to share,” said its PR agency in an email response.

Harley-Davidson’s love story in India, which started a decade ago, suddenly has a post script of betrayal.

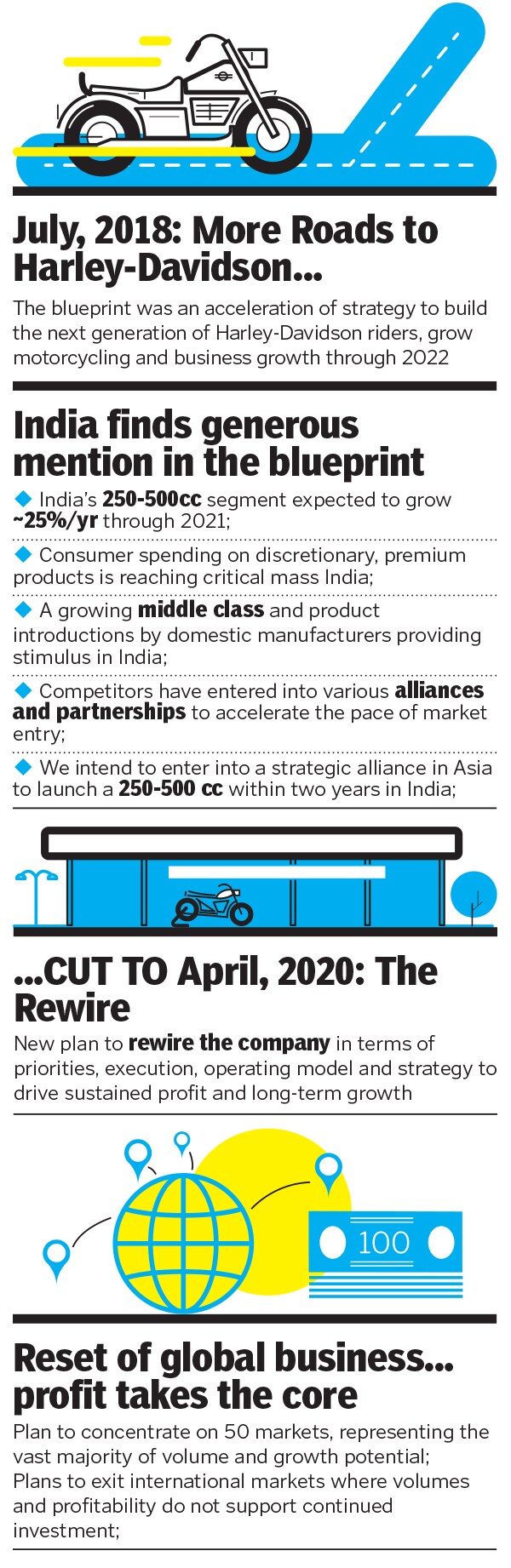

Graphic: Sameer Pawar

Till two years ago, the honeymoon was in full bloom. In July 2018, in its ‘More Roads to Harley-Davidson’ strategic global blueprint to build the next generation of Harley riders, India figured prominently. “A growing middle class and product introductions by domestic manufacturers is providing a stimulus in India,” the document highlighted. Competitors have entered various alliances and partnerships to accelerate the pace of market entry. Outlining that the market for 500cc plus had seen a steady growth in India, the paper estimated the segment to grow at a CAGR of 18% to 28% between 2017 and 2020. “Consumer spending on discretionary, premium products is reaching critical mass in China, India and Southeast Asia,” it reckoned.

The upbeat mood was understandable. In the fourth quarter of 2018, sales from emerging markets were up 18.7 percent, driven by double-digit growth in several markets including China, Brazil and India. The future looked promising. Harley-Davidson, the vision document outlined, intended to enter into a strategic alliance to launch a 250-500 cc bike within two years in India.

Cut to September 2020. The news of Harley-Davidson scouting for potential partners in India has flooded the Indian media. From Bajaj Auto, which already has a partnership with KTM and Triumph, to Hero MotoCorp and M&M, everyone is reportedly in the fray. Hero MotoCorp, the Indian player most touted to join hands with H-D, didn’t reply to an email sent by Forbes India.

From ‘More Roads’ to ‘The Rewire,’ auto analysts explain what led to the short circuiting in India.

“It had become obese,” says Amit Kaushik, managing director at Urban Science, a Detroit-based global consulting firm. H-D, which had an exciting start in India and replicated its global cult following in the country, failed to make the most of the euphoria. Bikes were highly over-priced—Rs 5 lakh to above Rs 50 lakh—by Indian standards. Moreover, the appetite for 1000 cc plus bikes in India was not even moderate.

Still, thanks to the charisma of the brand, it did manage to build a loyal following. The cheapest version—Street 750—was rolled out in 2014, then reportedly priced at Rs 4.1 lakh, and gave the brand a firm foothold in the Indian market in terms of volumes but another problem started brewing three years later when Vikram Pawah quit H-D as managing director in a little under one-and-a-half years in January 2017. “It started a period of instability in the Indian operations,” says Kaushik. The company, he adds, remained headless over the next few quarters.

When Jochen Zeitz took over as chief executive, he candidly admitted the problems with

When Jochen Zeitz took over as chief executive, he candidly admitted the problems with

the company"s strategy

The internal turmoil coincided with a global outburst, especially by US President Donald Trump, who had been lashing out at India for imposing high customs duty on H-D bikes. In June last year, Trump called the import duty ‘unacceptable’ in one of his tweets. In 2018, India had cut the duty on completely built units (CBUs) from 100 to 50 percent for the 800 cc plus segment.

In spite of much buzz about H-D facing unfair treatment in India, the ground reality depicted a dramatically different picture. “They were singed by a Catch-22 situation,” says a chief marketing officer of a rival international superbike maker, requesting anonymity. “The blessing became a curse,” he says. After over five years of living with a ‘Fat Boy’ price tag, H-D rolled out its cheapest bike and lowest cc engine in 2014 with Street 750. In fact, it started assembly at the Bawal plant, and started exports as well.

Street 750, the CMO explains, solved the biggest pain point of H-D, and consumers started lapping up the product. “In fact, until now, about 60% to 65% of H-D bikes sold in India are Street 750,” he says, debunking the myth around high customs duty. Bikes above 1000cc, the ones with the high customs duty, accounted for under 10% of sales. Even after the duty was slashed to 50%, it didn’t boost volumes, adds the CMO.

Meanwhile in 2019, the 750 series began to hurt H-D. In February, as a part of a global recall, H-D reportedly cited faulty brake calipers on the Street 750 and Street Rod 750. The recall was not the first one. In August 2015, the Street 750 was recalled to fix a faulty seal in the fuel pump.

The recall in 2019, though, did much damage. Demand never rebounded completely for the Street, and excitement for Rod 750, which was over a lakh costlier than Street, too started to peter out. The 750 series was problematic on another front too: Profit. For a brand used to hefty profit margins, the 750 was not the right choice. “It gave H-D volumes, but no margin,” says the top honcho of the above mentioned rival brand. “H-D is known for profitable growth.”

Back in the US, muted sales had started to take a toll. In February this year, chief executive officer Matt Levatich—the man behind ‘More Roads to Harley-Davidson’ and who joined Harley in 1994—stepped down, making way for Jochen Zeitz, known for reviving the Puma sneaker brand. The homeland of Harley has reportedly seen only one quarter of retail sales growth over the past 21 quarters. The situation was alarming, and Zeitz candidly admitted the problem. “We"ll continue to move forward with the highest potential elements of More Roads, but our strategy must be reassessed,” he reportedly said in April this year. The company, he pointed out, had over-indexed on new riders and new market growth and lost focus on critical profit sources.

What came next was Zeitz’s new H-D vision: Rewire. A critical component of the new plan was sharp focus on profit, investing in the markets, products and customers that offer the most profit and potential. In July this year, Zeitz outlined a bolder plan: Concentrating on 50 markets primarily in North America, Europe and parts of Asia-Pacific that represent the vast majority of the company"s volume and growth potential. The company, H-D said in its media release, is evaluating plans to exit international markets where volumes and profitability do not support continued investment in line with the future strategy.

Back in India, a country that got short-circuited due to the Rewire, analyst Jaspreet Singh Bajwa punches holes in the new vision. Harley, he explains, has shifted its focus on shareholder value maximisation. “This is short term thinking,” says the management consultant (automotive industrial consulting group) at Nomura Research Institute. Voices of shareholders have become more important than the customers. The source of the problem, Bajwa adds, stems from the global headquarters. “Over time, a rash of bad managerial decisions trickled down to the overseas markets,” he says.

Analyst Jaspreet Singh Bajwa, a passionate biker himself, says the company must look at a long-term vision

A passionate H-D biker himself, Bajwa outlines another fault line for Harley in India: Reckless expansion across the country. “Did it make sense to enter into cities where HNIs are below 1%?” he asks. A better option would have been to target metros and promising tier-1 cities where a majority of the country’s wealth rests. “Building the brand, retaining customers and increasing loyalty towards the brand should have been the focus,” he says. “Moreover, the competition was offering much more value at an equal or comparatively lower price,” he says. For new riders, a value offering product is equally or more important than community building and brotherhood, Bajwa adds.

The absence of a local partnership added to the woes. “BMW tied up with TVS, and Triumph tied up with Bajaj,” he says. “It’s not late. They should hunt for an Indian partner,” he says.

Back in Mumbai, Kumar has broken all emotional bonds. “A brand that has left me and so many riders in lurch has lost us, even if it returns in a new avatar,” he says.

First Published: Sep 29, 2020, 14:57

Subscribe Now