Today, India is the world’s fifth-largest and the fastest-growing global economy. In the previous quarter, the economy beat estimates and grew at 7.6 percent. Over the past decade, a majority government has implemented major reforms to fast-track growth, recapitalise public-sector banks, and clampdown on NPAs. The South Asian country steered out of the Covid crisis with a few scars but was able to restore financial and macroeconomic stability. In fact, it is one of the most attractive markets for foreign investors.

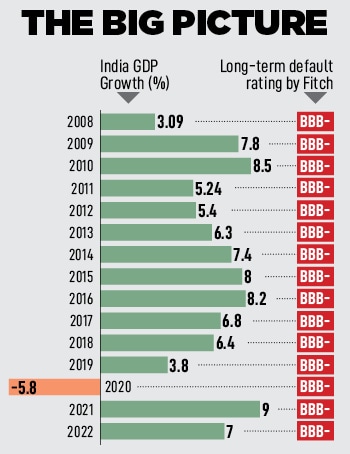

But global credit rating agencies have not budged (see table). S&P and Fitch have held on to a BBB rating for India while Moody’s continues to rate India at Baa3. These are the lowest possible sovereign credit ratings and indicate a high credit risk profile, which Sanjeev Sanyal, member, Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, argues is not an objective assessment of India given its strong economic progress.

In Re-examining Narratives, a collection of essays released by the Finance Ministry of India, the government questions the “opaque" methodologies used by credit rating agencies for sovereign ratings. “These ratings are important as they are binding constraints for developing economies, hindering their ability to attract necessary funds," it says in the report, which highlights the need for urgent reforms in the credit ratings system as it calls for a level credit field for cheaper global capital. “Such reforms will enhance the developing countries" ability to raise long-term financial resources from both domestic and international markets by significantly reducing funding costs and, hence, supporting them in their development goals."

![]()

Bank of Baroda’s chief economist Madan Sabnavis agrees that the methodology is biased and unfair. “Conceptually, rating agencies have erred because they are using the same yardstick for emerging and developed countries, which is not right," he points out. “Rating agencies need to relook at their methodologies and not just look at plain numbers but understand the context." He believes that India’s credit rating should be in the A-category.

So, what are the main gaps in their methodology or data gathering process?

Sanyal explains: “There are serious issues with the biased methodologies used by global rating agencies. One major issue is that around 20 percent of the weightage in the sovereign rating is driven by subjective indicators of governance, political stability and so on. As I have pointed out repeatedly in my writings, most of these inputs are generated by Western think-tanks and NGOs that are neither accountable to anyone nor transparent about their methodologies. Indeed, they are usually just the “opinions" of unknown “experts". There are other issues as well—for instance, the use of per capita income as an indicator of willingness to pay. This is odd as there is nothing to suggest that the rich are more willing to repay debt than the poor. Even if this is to be seen in terms of a minimum standard of living, surely it makes sense to look at it in purchasing power parity terms that would sharply boost India’s ratings."

Forbes India sought comments from S&P, Fitch Ratings, and Moody’s on whether the big three rating agencies considered the need to re-evaluate their process for better transparency and objectivity in their assessment. Moody’s and S&P did not offer comments.

Fitch Ratings told Forbes India: “All Fitch’s sovereign rating decisions are taken solely in accordance with one globally consistent and publicly available rating criteria, with rating drivers and sensitivities clearly identified in our ongoing public rating commentary. Rating decisions are based on independent, robust, transparent and timely analysis."

![]()

S&P Global says the foundation of its sovereign credit analysis rests on institutional, economic, external, fiscal, and monetary assessment. “Both quantitative factors and qualitative considerations form the basis for these forward-looking assessments", it says in a note available on its website. “Our sovereign rating criteria incorporate the factors that we believe affect a sovereign government"s willingness and ability to service its financial obligations to nonofficial creditors on time and in full."

Despite assigning India the lowest investment grade, in a note dated May 18, S&P says India’s economy is performing well amid global challenges and it anticipates sound fundamentals to underpin growth over the next two to three years. Furthermore, it believes India’s sound economic fundamentals will be sufficient to offset the government’s weak fiscal performance and help it sustain elevated government funding needs and a high interest burden over the next 24 months.

“We may raise the ratings if India"s fiscal metrics dramatically improve, on a sustained basis. We may also raise the ratings if we observe a sustained and substantial improvement in the central bank"s monetary policy effectiveness and credibility, such that inflation is managed at a durably lower rate over time," it adds.

![]()

However, as the North Block highlights, India’s heft as a global economic engine and its sound monetary policy present a timely case for a ratings upgrade. It says in the report, “The share of India"s total trade in GDP has risen significantly from around 15 percent in the early 1990s to almost 50 percent in 2022… the increasing share of technology-intensive products in India’s export basket and a surge in India"s contribution to high-value-added services exports have rendered India"s trade basket resilient to external shocks. These developments in India"s export sector have been catalysed by a facilitative ecosystem by the government, and they will enable India to assume a key position in global supply chains."

![]() In the past, the lack of policy reforms and sluggish growth are among the key grievances of global rating agencies with regard to their reservations on upgrading their investment grade for India. They have routinely raised concerns about fiscal discipline and the credibility of the government’s fiscal roadmap. Missed divestment targets is another area of worry, according to those in the know.

In the past, the lack of policy reforms and sluggish growth are among the key grievances of global rating agencies with regard to their reservations on upgrading their investment grade for India. They have routinely raised concerns about fiscal discipline and the credibility of the government’s fiscal roadmap. Missed divestment targets is another area of worry, according to those in the know.

But do these concerns compromise the nation’s ability to repay debt and are these valid reasons for holding back an upgrade?

The quality of government spending has improved with higher allocations for capital expenditure to boost infrastructure development to create jobs and spur growth. Also, macro indicators are healthy capital flows are robust, forex reserves stand above $600 billion, and government debt has declined to around 80 percent of GDP. Importantly, unlike most emerging market peers, the bulk of India’s foreign debt is in Indian rupee. “There is zero risk to the rest of the world because the government has to repay investors in rupee," Sabnavis says. Also, for the record, independent India has never defaulted on its debt payments.

Interestingly, since November 2008, Fitch Ratings, for example, has reaffirmed an A+ rating for China. In the last four years, China has raised multiple concerns: Uneasy trade relations with the US, rising geopolitical conflict, crackdowns on private companies, an unfolding crisis in the property market, lack of investor and consumer confidence, and tepid growth. But the rating agencies don’t seem to be overly worried about China’s declining state of quantitative factors and qualitative considerations and the risks associated with higher government debt.

![]() “The Chinese government’s indications that policy measures next year will prioritise development provide greater assurance about China"s economic growth prospects. However, this could result in higher fiscal deficits and debt than we expected previously, at a time when contingent liability risks have increased for the government," Fitch said in December.

“The Chinese government’s indications that policy measures next year will prioritise development provide greater assurance about China"s economic growth prospects. However, this could result in higher fiscal deficits and debt than we expected previously, at a time when contingent liability risks have increased for the government," Fitch said in December.

If the mood of market investors offers any clue, India’s high popularity as an attractive investment destination of choice foreign investors belies its low credit ratings. After decades of poor returns, investors are flocking out of China into countries such as India for better and stable long-term returns. On Thursday, FDI inflows into India touched a 21-month high at $5.9 billion in October.

But can India reduce reliance on global rating agencies?

“In the short term, we can do little more than challenge the methodologies and create a public debate around the use of specific indicators that are unfair. Longer term, India needs to create its own credit agencies and think-tanks that have the capability to judge the world and issue their own ratings and rankings. This is not just about sovereign ratings but also other areas like environmental, social and governance indicators, rankings of freedom and democracy, and so on," Sanyal concludes.

“India’s sovereign ratings have remained at the lowest rung of investment grade for many years despite a dramatic improvement in its economic capability and prospects. India is not merely the world’s fastest-growing major economy, its ability to repay external debt is exceptionally good. India holds over $600 billion in foreign exchange reserves, its public debt is mostly in Indian rupees, its banking system is well capitalised and its corporate sector is profitable. By any objective measure, India should be rated two notches above current levels," Sanyal tells Forbes India.

“India’s sovereign ratings have remained at the lowest rung of investment grade for many years despite a dramatic improvement in its economic capability and prospects. India is not merely the world’s fastest-growing major economy, its ability to repay external debt is exceptionally good. India holds over $600 billion in foreign exchange reserves, its public debt is mostly in Indian rupees, its banking system is well capitalised and its corporate sector is profitable. By any objective measure, India should be rated two notches above current levels," Sanyal tells Forbes India.

In the past, the lack of policy reforms and sluggish growth are among the key grievances of global rating agencies with regard to their reservations on upgrading their investment grade for India. They have routinely raised concerns about fiscal discipline and the credibility of the government’s fiscal roadmap. Missed divestment targets is another area of worry, according to those in the know.

In the past, the lack of policy reforms and sluggish growth are among the key grievances of global rating agencies with regard to their reservations on upgrading their investment grade for India. They have routinely raised concerns about fiscal discipline and the credibility of the government’s fiscal roadmap. Missed divestment targets is another area of worry, according to those in the know. “The Chinese government’s indications that policy measures next year will prioritise development provide greater assurance about China"s economic growth prospects. However, this could result in higher fiscal deficits and debt than we expected previously, at a time when contingent liability risks have increased for the government," Fitch said in December.

“The Chinese government’s indications that policy measures next year will prioritise development provide greater assurance about China"s economic growth prospects. However, this could result in higher fiscal deficits and debt than we expected previously, at a time when contingent liability risks have increased for the government," Fitch said in December.