A couple of years ago, as he was driving along the roads of Saket, the hustling upmarket business district in New Delhi, Akshay Munjal came across a few advertisements.

‘Wanted: Graduates or engineers to drive luxury cars’, said the posters stuck across boards near Select City Walk Mall in Saket. Munjal, the grandson of Brij Mohan Munjal, founder of the $5 billion Hero Group, was already a founder at the seven-year-old BML Munjal University in Gurugram, and the man responsible for the group’s education foray in 2014.

“I still have a photo of that poster," says Munjal. “By the way, the poster is still there in some places in Saket and its nearby area. The reality is that a large percentage of our graduates, whether engineers or management graduates, and others are unemployed or underemployed. Somebody is working as a driver after graduating in engineering. To me, that"s not commensurate to the skills they have."

“Since I was a part of the higher education sector in India, I took it personally," says Munjal. “First, we put a team within the university to see what we can do to fix the problem. But we realised that it will create so much confusion within the university. Universities are centres of knowledge and the role of a tier-one university in India and globally should be to create knowledge."

That meant, Munjal and his team had to look elsewhere to find solutions. Over the next two years, they put together a team that identified jobs of the future in collaboration with the industry, and tied up with “some of the best universities" in the world to develop programmes. “We don"t consider ourselves an education technology company," says the 40 year old. “We consider ourselves as a learning company that uses technology and many other tools to make learning effective."

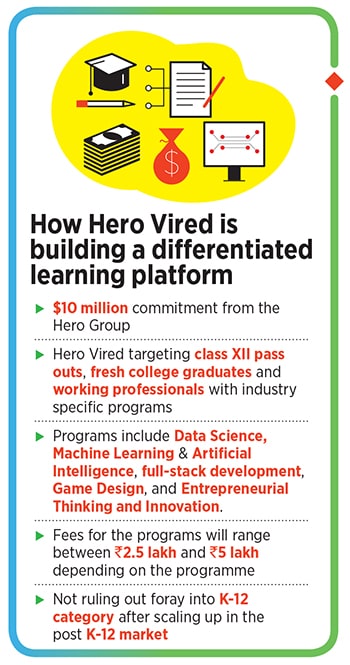

On April 13, exactly 65 years after his grandfather set up Hero Cycles, Munjal set up Hero Vired, an online learning platform that offers an end-to-end learning ecosystem for professional development, and makes them industry-ready for employment. For now, the company is targeting three categories of students, those who have passed class XII and in the process have become an alternative to what Munjal claims as “tier 3 and tier 4 colleges in the country" in addition to fresh college graduates and working professionals looking to upskill.

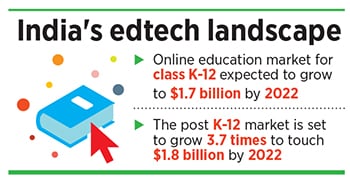

The company hasn’t ruled out a possibility of entering the lucrative K-12 segment, which has seen the likes of Byju’s, Unacademy and Toppr slug it out in recent times. India’s edtech industry has been flush with funds with money from venture capitalists in recent years, pushing the sector into one of the most sought-after businesses in the startup ecosystem in the country.

Vired, Munjal says, offers interactive support, peer-to-peer communication, and engagement-driven online instructor-led classes, and the areas of learning range from certificate programmes in finance and related technologies to integrated programmes in data science, machine learning and artificial intelligence in addition to full-stack development, game design, and entrepreneurial thinking and innovation.

The platform has partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and New York-based Codecademy, among others. “We conducted an exhaustive survey, and came up with a set of jobs, which are required today and expected to continue being hot for the next five years," says Munjal. “The big picture we"re trying to solve is one of employability and under employability."

![hero vired hero vired]() Hero Vired will offer programs for class XII pass outs, college graduates and working professionals with industry specific programs Image: Xavier Galiana/ AFP

Hero Vired will offer programs for class XII pass outs, college graduates and working professionals with industry specific programs Image: Xavier Galiana/ AFP

What’s the plan?

For now, much of what Munjal and his team are trying to solve is on two fronts. One is to help bring access to quality education and providing a viable alternative to the existing ecosystem that has been struggling with quality issues.

Over the past 70 years, while the number of universities in India increased from 20 to 993, and colleges went up from nearly 500 to almost 40,000, the quality imparted at the institutes has been a cause of worry. That had even prompted the University Grants Commission to bring out a ‘quality mandate’ that sought to improve the quality of teachers, impart life skills to students, and change the assessment pattern to improve the quality of education in higher studies.

In engineering, for instance, between 70 and 90 percent of the people graduating are unemployable, reckons Munjal. “There are four-lakh-plus All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE)-approved colleges in India," says Munjal. The AICTE is a statutory body and a national-level council for technical education. “That means some 36 lakh engineering seats are approved in those colleges alone. This is outside the university system, which means there is a large percentage of our population which goes to tier 3 or 4 colleges, after having spent substantial money," says Munjal, who reckons the fees to be upwards of Rs8 lakh over a four-year programme.

“They"ll be fortunate if they get a job," adds Munjal. “There again, the salary will be between Rs4 lakh and Rs5 lakh. If you look at tier 3 or 4 college students, they struggle to get meaningful employment. That’s the case across engineering or management courses. That’s a problem we are trying to solve." India’s Gross Enrolment Ratio, the ratio of persons enrolled in higher educational institutions, to the total people in the 18-23 age group stands at 26.3 percent. That is in stark contrast to about 36 percent for countries in transition and 54.6 percent for developed countries.

“So, just by saying I will open more colleges, I’m not addressing the issue of improbability," says Munjal. “I may just end up creating more people who are unemployable. To give them an alternative, we identified these programmes that can help."

That apart, the company is also looking to focus on providing programmes for working professionals. “Unfortunately, learning stops the day you walk out of college, the day you graduate," says Munjal. “Today, as new technologies come in, this whole system of saying once I"ve graduated, I don"t need to learn anything more will become obsolete." Last year, a study by US-based online learning platform Udemy said 92 percent of employees in India felt skill gaps in their jobs, and as many as two-thirds felt personally affected by them.

![hero vired 1 hero vired 1]()

“The fact is many of the jobs today will undergo dramatic changes in the next few years," says Narayanan Ramaswamy, head-education & skill development at consultancy firm KPMG. “And upskilling and reskilling are absolute necessities now. This is a huge untapped market and Hero is right in going after a market that’s beyond the regular edtech space."

Hero Vired’s online courses currently run for a year or six months based on the course. While there are recorded classes, the company promotes regular interaction with who Munjal refers to as some of the “best faculty" in the world. “We want to build a real alternative to tier 3 and 4 education," he says. “It doesn’t make sense to spend four years in college and have zero skills that will help me get employment." Fees for the programmes offered by Vired range between Rs2.5 lakh and Rs5 lakh, depending on the programme, with sessions likely to begin by July this year.

In all, the family has committed $10 million towards developing Hero Vired over the next few years. “If you look at what most online or edtech companies are doing now… they try to provide a recording of the class and that’s a sub-optimum way of teaching because when a teacher teaches in a class, his or her connect with the student is different," says Munjal.

In the process, the company claims it has built a mechanism to measure learning outcomes and provide insights based on constant evaluation of students. “You may be great in learning from a book," Munjal explains. “Somebody else might pick up better through a different mean. Online education today gives the flexibility to customise and provide personalised assessment for each student, and then measure it."

Can it really work?

“They are doing the right thing, even if they are a little late," says Ramaswamy of KPMG. “There are huge opportunities emerging in the area of sustaining jobs, and every single person is looking to do some kind of a booster programme." Much of that, Ramaswamy reckons, comes from a naturally created gap in every stage of education in the country.

“The big commercial opportunities in this country in the education space have come in the in-betweens," says Ramaswamy. “After school, you have to go through some coaching centres because the education at school hasn’t been great. After college, you have to do some preparation because the quality of education at colleges hasn’t been good. Then, when you join a company, you have to go through long periods of training because the training in colleges isn’t adequate. That’s a big market."

Take, for instance, Infosys, India’s IT bellwether, which runs a training centre in Mysuru—considered as one of India’s biggest training campuses. The company trains some 10,000 students, often referring to the centre as a second college after graduation. “By any measure, 1 to 1.5 million people are joining our workforce every month," says Aurobindo Saxena, independent education consultant and former head of education practice at consultancy firm Technopak. “Post Covid, many of the legacy business models have become defunct and demand for the workforce is emanating from new-age companies for 21st century technical skills."

That’s precisely the opportunity that Munjal is gearing up to tap. “If you look at education, there is no one brand effectively which can cut across segments," says Munjal. “If you look at an IIM or IIT or a Doon school, they are in different segments. They are all in education, but it doesn"t mean somebody good at postgraduate teaching can do K-12. To me, an alternative to tier three and tier four colleges and working professionals is such a large market. In education, nobody in the world can talk about market share in their country. Each segment is so big."

![hero vired 2 hero vired 2]()

India’s education sector is estimated to be worth some $117 billion with around 360 million learners in 2019-20, according to a report by Indian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association and PGA Labs. Of this, around $49 billion is spent on school education while around $42 billion is spent on supplementary education, comprising private coaching and test preparation. The country’s online education market for classes 1 to 12 is projected to grow to $1.7 billion by 2022 while the post K-12 market is set to grow 3.7 times to touch $1.8 billion, according to a report by RedSeer and Omidyar Network India.

The market that Munjal and Hero have now forayed into was once called the MOOCs or massive open online courses with players like Coursera, EdX, Udacity and Udemy, reckons Saxena. “The content was virtually free with a low cost of certification, but as a result, the completion rates were also around 7 to 8 percent," he explains. “Over a period of time, this evolved into SPOCs or small private online courses, typically on campus, with higher degrees of engagement and completion rates. Hero Vired has adopted this model with smaller batch sizes of maximum 100 students per batch per programme and partnered with Ivy League Universities."

Over the next few months, Munjal has laid out elaborate plans to partner with more universities across the world for specific programmes to ramp up the platform’s offering. It also helps that the platform is backed by the Hero group, among one of the country’s biggest business houses. “In this particular segment, industry acceptance and recognition are important parameters for selection of courses by students," says Saxena. “Hero group can easily provide industry projects, sessions with industry experts and exposure to real-life projects."

That could also mean an opportunity to develop partnerships with companies and businesses to train their workforce besides helping build a steady supply of workforce for organisational requirements. “If someone earns Rs6 lakh per annum and after completing this course for a fee of Rs4 lakh in six months, one can get a job of Rs15 lakh per annum or more, I am sure you don’t need a consultant to tell you that the demand for such programmes will be immense," says Saxena.

That’s precisely why Munjal is only considering a foray into the K-12 business once he can solve the problem of underemployment. “I think if we solve this, it will be a huge achievement… so why not?" says Munjal about foraying into the lucrative K-12 market. “There"s a lot of noise in this sector. At the same time, given the Hero brand, given our partners, we"re not looking at large numbers in the first year. We want do this this brick by brick. Because once you"ve got the foundation right, you can always step on the gas and focus on quality."

Much of that also has to do with the family’s firm backing and commitment towards the business, which has meant that the business isn’t in dire need to generate revenue. Also, the Hero group has recently forayed into areas such as clean energy, finance and even manufacturing of electronics. “I don"t need to show growth rate because we want to look at this business the way we built our other businesses," says Munjal. “We want to build businesses that last generations and solve a relevant problem for a large part of the world. Because when you want to do things overnight, they tend to crash overnight as well. We want to focus on the basics, we want to focus on getting the core right."

Who better than a Munjal scion to know about building it brick by brick.

Akshay Munjal, Founder and CEO, Hero Vired

Akshay Munjal, Founder and CEO, Hero Vired Hero Vired will offer programs for class XII pass outs, college graduates and working professionals with industry specific programs Image: Xavier Galiana/ AFP

Hero Vired will offer programs for class XII pass outs, college graduates and working professionals with industry specific programs Image: Xavier Galiana/ AFP