Bandhan Bank aims for the big league

Bandhan Bank is working to reduce its exposure to microfinance, in which it was rooted, and is now focusing on deposits and loans to drive growth

Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, Ceo and MD of Bandhan Bank, is confident of making the most of the still low levels of financial inclusion in rural India

Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, Ceo and MD of Bandhan Bank, is confident of making the most of the still low levels of financial inclusion in rural India

Indranil Bhoumik for Forbes India[br] It is a cloudy, humid day and Chandan Yadav (36), a dairy farmer is tending to his cows and buffaloes on the land his family owns in Kishanganj, in the north-eastern region of Bihar. Yadav’s family-owned Akanksha Dairy Farm has more than doubled its sales of milk to 180 litres per day since 2016, thanks to the breeding of high milk-yielding animals at the farm. The milk is sold to the nearby Border Security Force camp in Khagra, besides two medical colleges and hospitals in the area.

The dairy provides livelihoods to all the six Yadav brothers and their families, generating about ₹6 lakh in income annually, of which over 60 percent is saved. Much of the expansion in the dairy business is thanks to the loan the Yadav family took from Bandhan Bank, where they have had a current account since 2008. “We have taken a ₹5 lakh loan for our business,” says Yadav, adding that he hopes to repay it by 2021. Yadav is also confident of banking in a more substantial manner with Bandhan Bank in the coming years: He plans to double the amount of loan he has taken in 2022 to “set up a milk-labelling and packing centre” at the same place.

Moumita Sur (25) first banked with Bandhan in 2013 as part of a women’s group micro-loan of ₹10,000. By 2016, she had turned into a small entrepreneur: She and husband Biswajit set up a company, Ganpati Enterprise, in Howrah, Kolkata’s neighbouring district, manufacturing steel and wrought iron furniture that is sold to retail firms in Bihar, Odisha and Jharkhand.

With a steady clientele and annual sales of ₹1.2 crore, Sur is confident of growing her business further. “Work restarted slowly in June and has picked up now,” she says. Sur now has a business loan of ₹10 lakh from Bandhan, which she will repay soon. “There will be a need for more loans, though,” she adds.

It is customers such as Yadav and Sur, whose business units have grown in recent years—and the trust factor they share with the bank—who give Bandhan the confidence that it can continue to build its deposit base and expand its reach.

Moumita and Biswajit Sur set up a steel and wrought iron manufacturing unit in Howrah, West Bengal, with a loan from Bandhan Bank [br]

Moumita and Biswajit Sur set up a steel and wrought iron manufacturing unit in Howrah, West Bengal, with a loan from Bandhan Bank [br]

Bandhan Bank claims that half of its 20.3 million customers are unique, which means they have not banked with any other institution before. Stickability of customers is always a positive for a bank and customers such as Yadav and Sur can rise financially and become the bank’s emerging entrepreneurs, a new business vertical created by Bandhan Bank in September. The bank has identified this as one of its growth engines—besides mortgage lending—as several of its current micro-finance customers start setting up their own businesses.

The micro-and small-business enterprises segment—which is the Emerging Entrepreneurs Business—forms 4.2 percent (₹3,150 crore) of the bank’s total loan book of ₹74,330 crore.

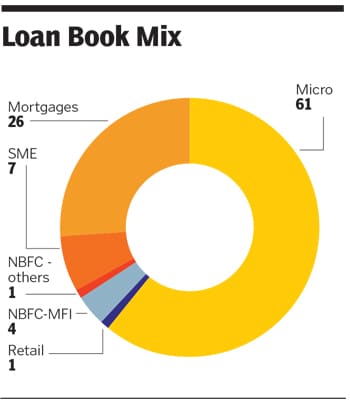

Deposit focussed

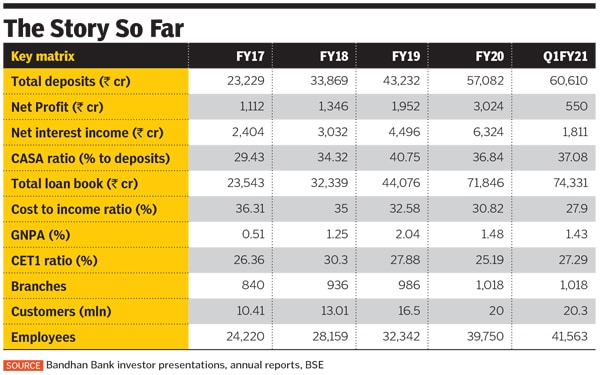

After becoming a bank in August 2015, Bandhan is now in the midst of a transformation, diversifying its revenue base while gradually lowering its exposure to microfinance lending, which was once its roots. Bandhan is not only identifying and lending larger ticket-sized loans to emerging entrepreneurs, it is equally focussed on expanding its mortgage lending business. In October, the bank completed a year of mortgage lending after acquiring affordable housing firm Gruh Finance from HDFC in 2019. About 61 percent of its loan book still comprises micro-loans, while 27 percent comes from new businesses such as mortgage lending and retail. The bank has finalised plans to hire and train more people over the next year to sell these mortgage and small business loans. All of this will help the bank diversify its loan book and reduce concentration of risk in microfinance lending. Chandan Yadav, a dairy farmer in Bihar’s Kishanganj, is looking to take further loans from Bandhan Bank to expand his business[br]Bandhan Bank’s Managing Director and CEO Chandra Shekhar Ghosh appears satisfied as he speaks to Forbes India from his Kolkata headquarters over Zoom. “This was a question posed even when we became a bank. I am confident that there is enough scope to grow deposits,” he says, citing the still low financial inclusion factor in rural India. Only 11 percent of bank branches in India serve two-thirds of the rural population.

Chandan Yadav, a dairy farmer in Bihar’s Kishanganj, is looking to take further loans from Bandhan Bank to expand his business[br]Bandhan Bank’s Managing Director and CEO Chandra Shekhar Ghosh appears satisfied as he speaks to Forbes India from his Kolkata headquarters over Zoom. “This was a question posed even when we became a bank. I am confident that there is enough scope to grow deposits,” he says, citing the still low financial inclusion factor in rural India. Only 11 percent of bank branches in India serve two-thirds of the rural population.

Bandhan has seen a steady pace of growth in deposits. This has seen the bank boost its CASA (current and savings account) ratio to 37 percent, which is impressive for a young bank. CASA as a percentage of deposits is 33.7 for IDFC First Bank and 25.8 for Yes Bank. The bank’s cost of funds is also improving. Higher deposits help a bank lend money to customers at a rate higher than its cost of funds. Bandhan’s cost of funds stands at 6.4 percent, as against 7.1 percent in March 2018.

The bank has also built on its physical presence. “Bandhan is built on a high-touch model and trust in banking is built on a physical, not virtual, presence. We need more physical branches,” Ghosh says. The number of branches has grown to 1,123 from 501 in 2015. It had about 2,022 micro credit-banking units, which have now grown to 3,541 across the country, to serve these category of customers. Ghosh hopes to increase the liability franchise (deposit-taking centres) to 3,000, and the micro credit units to around 5,500, in the next five years.

Ghosh is confident of the expansion plan. Setting up a branch in rural or semi-urban India could cost ₹10 lakh to ₹15 lakh, and ₹25 lakh to ₹30 lakh in the metros. In the coming years, the bank will reduce its exposure to micro-lending from the current 61 percent to about 40 percent. This will mean continuing to convert a portion of its micro-credit banking units into deposit-taking centres. The near-term plan is to convert 300 banking units into deposit-collection centres by the end of 2020.

Bandhan has also recruited 3,000 employees since the lockdown to boost deposit and EEB-based lending activity. It has 11 training centres across India, which trains over 3,500 employees each month. Stickability is strong in the Bandhan workforce too: 70 percent of its staff has worked only in Bandhan.However, even a year after the acquisition of Gruh Finance, it remains a work in progress. Sale of affordable housing and disbursement for loans continue to be sluggish. The total advances in the mortgage lending business edged up just 3.9 percent to ₹19,561 crore in Q1FY21, up from ₹18,822 crore a year earlier. This is pro-forma as Gruh was a separate entity at that time.

But the acquisition of Gruh complemented Bandhan’s activities: As the bank’s borrowers’ businesses grew, so would their need for loans, including for a house. Gruh’s geographical strength is in western and central India, while Bandhan’s is in the east and north east.

While realty developers continue to be wary of expanding their presence, or even launching new affordable housing projects, the activity expands through what is called family-led rather than developer-led construction. This is when a family with a plot of land gets a small contractor and builds a house. Prior to the merger with Bandhan, at least 50 to 60 percent of properties that Gruh financed were self-constructed in rural India, say former Gruh officials. The problem with this activity is that the pace of growth is sporadic, and demand for loans cannot be mapped. Historically, too, affordable housing developers have not set up offices in regions where population density and demand are weak.

“This business will take some time to grow,” Ghosh admits. But the bank’s growth plan is in place—Bandhan plans to open more mortgage lending branches, touching 400 by March 2021 from the current 106.

Challenging Times

Like most lending institutions, Bandhan Bank too has had a rough three months of business after the pandemic-induced lockdowns. There were two months of complete lockdown, followed by a partial opening up in June, and substantial easing of restrictions in August and September. Now, the bank’s collection efficiency—the number of people who have paid back loans out of the total borrowers—also continues to improve each month.

Collection efficiency for the bank is at 90 percent from near zero in April. Other microfinance lenders are seeing a collection efficiency of between 85 to 90 percent. “We hope to touch 98 percent by the year-end,” says Ghosh.

Rural India, where the bank is more active, has seen a pick-up in business activity since June. This is despite the increase in the number of Covid-19 cases across states such as Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Retail trade too is starting to pick up, leading to a rise in the bank’s activities.

“The bank’s customers in agriculture and allied businesses, food processing, small retail stores and micro-credit are starting to take loans of ₹20,000 to ₹30,000 to restart business activities,” says Ghosh.

Several of Bandhan’s customers have kept their incomes consistent by switching jobs during the lockdown. But, as of June, around 24 percent of Bandhan Bank’s total loan book is under moratorium. This is what needs to be monitored closely. Ghosh does not anticipate the number of borrowers who are unable to repay any instalment to be significant. But Bandhan, like rival banks, has decided to be prudent by increasing Covid-19-related provisioning.

The bank has made a high Covid-19 provisioning of 8.6 percent of the overall loan under moratorium, according to rating agency ICRA in a June-end report, to cushion any losses that may arise due to non-recovery of loans on account of Covid-19. This is higher than ICICI Bank’s 7.5 percent and HDFC Bank’s 6.1 percent. Only non-banking financial company Bajaj Finance—which has a risky exposure of unsecured loans in its loan book—has maintained a higher contingency provisioning of 10.8 percent, as of June 2020.

Ghosh also believes that they understand their customers well and repayments are collected on the basis of electronic clearing services (ECS) debits. Therefore, if and when there are any ECS mandates that don’t get honoured, it serves as an early warning system for the bank.

Ghosh has one contentious issue to deal with: To continue to reduce the promoter stake in the bank from the current 40 percent to a final 15 percent in 12 years of starting the company, as mandated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). He has already reduced the promoter stake from 82 percent in 2018 to 40 percent. The RBI had restricted Bandhan from expanding its branch network and had put a freeze on Ghosh’s salary in 2018 until the stake was reduced. These restrictions have been lifted in 2020.

These previous concerns and the lockdowns hurt its stock price, which fell 78 percent, from ₹702 in August 2018 on the BSE to ₹154.5 in March-end 2020. The stock has since doubled to ₹314.Now, besides identifying growth engines, the bank is also building a succession plan. Ghosh is the face of Bandhan, but it has built a core team of veteran bankers who lead various operations and has put a business continuity plan in place. The team includes former State Bank of India veterans Deepankar Bose (corporate centre) and Sanjeev Naryani (business), former Development Credit Bank employee Sunil Samdani (chief financial officer), former Bajaj Capital CEO Rahul Parikh (marketing head) and former ICICI Bank veterans Kumar Ashish (EEB) former Axis Bank veteran Santanu Banerjee (now HR head) and former RBI and Barclays Bank economist Siddhartha Sanyal (now chief economist at Bandhan Bank) and Biswajit Das (risk).

So far, the bank has managed to bounce back and grow from setbacks, whether it is the Andhra Pradesh microfinance crisis in 2010, the impact of demonetisation, or the Goods and Services Tax. And Ghosh remains confident that once the pandemic’s impact wanes, business and economic activity will be back.

But unlike previous emergency situations, the path the Covid-19 pandemic can take in India is unclear. “How will India’s businesses deal with the second wave of infections?” asks Alpesh Mehta, deputy head of research at Motilal Oswal Financial Services. “In microfinance, the willingness to pay is more important than the ability to pay.”

This will obviously become a critical issue for all banks to deal with if business conditions become more difficult. HP Singh, managing director and chairman of Satin Creditcare, an NBFC-MFI institution, is following the prudent approach of servicing existing borrowers rather than chasing new loan growth. “We expect a much stronger bounce-back in rural India, even if the second wave of Covid-19 comes,” Singh says.

So, although Ghosh is building the structure for a more robust bank by 2025, and most of Bandhan’s businesses are expected to grow to normal levels in the next two years, he will have to bank on the hope that the fortunes of its low-income borrowers’ do not get ravaged in the after-effect of the pandemic, which might increase asset quality concerns.

First Published: Nov 06, 2020, 10:39

Subscribe Now