India Inc in 2030: Debt won't be a bad word

Consumer debt, along with need for corporate debt, is likely to increase. But as economic growth expands in a low-inflation regime, debt may not be a huge concern in the next decade

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurThe current decade could well be one corporate India might want to forget quickly. It has been characterised by massive bank loan defaults by some well-known names in corporate India such as Bhushan Steel and Essar Steel. While such companies have found, or are poised to find, new owners through a resolution at tribunals, in other cases the realisation of claims by creditors and lenders continues.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurThe current decade could well be one corporate India might want to forget quickly. It has been characterised by massive bank loan defaults by some well-known names in corporate India such as Bhushan Steel and Essar Steel. While such companies have found, or are poised to find, new owners through a resolution at tribunals, in other cases the realisation of claims by creditors and lenders continues.

As we race towards the new decade, lending activity from banks continues to be impacted. Some of India’s largest lenders, State Bank of India and Punjab National Bank, have swallowed the bitter pill, unable to make recoveries after the collapse of Kingfisher Airlines, led by one-time billionaire Vijay Mallya, and a fraud carried out by fugitive diamond manufacturer Nirav Modi.

India Inc. of 2030 might look vastly different, say experts. As India moves into a low inflation-rate regime, interest rates are likely to remain benign in the early part of the next decade and debt may not be a cursed word for corporates.

Rising Debt

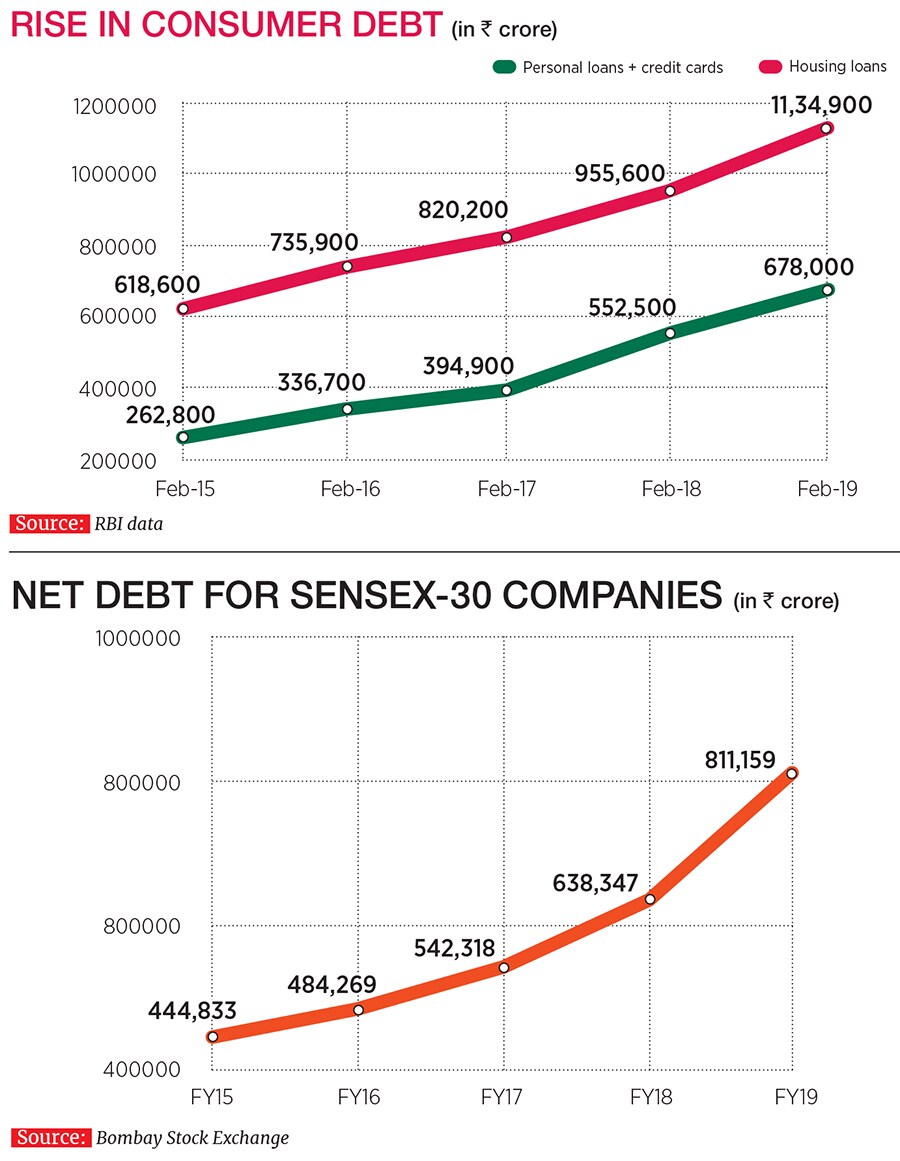

“While debt will continue to rise due to economic activity, consumer debt is expected to outpace corporate debt by 2030. Consumer debt will grow faster than corporate debt, albeit from a low base,” Ridham Desai, India equity strategist at Morgan Stanley, tells Forbes India. Banks are focussing on retail lending, considering that household debt—which includes lending towards personal loans, housing, auto, consumer durables and credit card activity—is surging. India’s household debt, though still way behind that in China (51.5 percent) and US (76.4 percent), is at 11.3 percent of India’s GDP, up from 8.7 percent in 2011.

India’s household debt, though still way behind that in China (51.5 percent) and US (76.4 percent), is at 11.3 percent of India’s GDP, up from 8.7 percent in 2011.

Disposable personal income in India grew over three times to ₹192 lakh crore in 2018 from ₹60 lakh crore in 2010, while consumer spending grew 175 percent to ₹2,067 crore from around ₹750 crore in the same period, according to Trading Economics data.

Tarun Ramadorai, professor of financial economics at London’s Imperial College says that India could witness rapid secured and unsecured lending in the coming years. “There is a lot of debt in the informal areas of rural India (through moneylending activity) which will continue to flow towards the formal sector,” Ramadorai says on the phone from London.

In the next decade, corporate debt will be static or will grow marginally but its percentage to GDP will fall. This figure was 17.14 percent in June 2018, RBI data showed.

One of the biggest contributors to a rise in overall debt will be ongoing mega-infrastructure projects, particularly the Mumbai Metro (Line 2-12), Mumbai Coastal Road project, New Delhi (Phase IV) and Namma metro in Bengaluru (Phase 2), all of which are set for completion in the next decade. But being government and state-led, the projects will be financed with a mix of debt and equity through special purpose vehicles (SPVs).

India may also not immediately be able to resolve the serious problem that its banks faced in the form of surging non-performing assets and provisioning towards the same. Poor decision-making in granting approvals for funding projects and weak business cycles contributed heavily to the cause, while the lack of a well-developed corporate bond market has only made matters worse.

India’s Comptroller and Auditor General Rajiv Mehrishi has identified this to be the cause for the NPA crisis, arguing that banks were constrained to lend through short-term deposits towards long gestation projects which later ran into trouble. For banks, this often resulted in divergences between liquidity and maturity of loans, academicians have observed.

The domestic debt market remains largely skewed towards government securities while the smaller corporate bond market is mainly confined to institutional investors.

Growth for several economies hinges on the level of recovery and whether the judicial process is quick and efficient, to avoid the scope for zombie lending, says Ramadorai.

“The country needs a strong credit defaults registry and legislature. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code is a necessity but is being tested. We are also not sure what road the RBI’s PCA (prompt corrective action) for banks will take,” he explains. [RBI’s PCA ensures that banks with a weak financial matrix are put under watch if they slip on norms relating to asset quality and profitability].

But for technology-driven startups, capital is not expected to be a concern in the next decade.

Private equity and venture capital funding for technology-backed companies has been on the rise—now at an estimated $36 billion in 2018 from just $8 billion in 2015. EY in a recent report indicates that PE/VC investments could jump to $65 billion in India by 2025, assuming that India will grow by approximately 7 percent year-on-year between now and 2025.

The future might also not be a challenge for debt-heavy corporates such as ONGC, Reliance Industries, Adani Group and Tata Steel which have expanded across more business lines and invested in infrastructure to generate trillion rupee revenues. They are likely to retain a momentum in business, size and credibility and enjoy relatively better bargaining power with banks and capital markets.

Harsh Goenka, the fifth-generation entrepreneur who is chairman of the $ 3.1 billion RPG Group, advocates the need for corporate debt in a judicious manner. “Some companies have clearly been cowboyish in their approach in dealing with debt. If they are viewing it as cash flow or going with the belief that business cycles will turn right, things will not work,” Goenka says. The RPG Group, with a power transmission EPC company KEC in its portfolio, has a debt equity ratio of 0:3.

Debt not a bad word

The coming decade will see corporate India move into a low-inflation phase. A concern about rise in crude oil prices for imports will continue into the next decade, with changing geo-political conditions impacting oil supply from Venezuela, Iran and Saudi Arabia. But most economists believe interest rates are likely to be benign in at least the first few years of the next decade.

“In the new regime [of Shaktikanta Das], the RBI seems to be more growth supportive and trying to have a less rigid interpretation of their inflation-targeting mandate,” says Siddhartha Sanyal, chief India economist with Barclays.

“If the RBI continues to be supportive on the liquidity side, and also maintains a pro-growth bias on the interest rates front, the combination should be positive for the next one to two years,” he explains.

India’s consumer price inflation rate stands at 2.86 percent, with the RBI forecasting inflation to be well below 4 percent in FY20.

In this scenario, depending on the demand a sector or a specific company is enjoying, having more debt may not be bad in the coming years.

“Inflation seems to be mostly benign and the twin deficits are anchored,” says Sanyal.

A global unicorn?

Economic growth for India will continue to be driven by the services sector. Agriculture contributes 15 to 17 percent, manufacturing another 15-17 percent, construction 10 percent and the majority 58-60 percent is through the services sector.

According to Morgan Stanley’s Desai, India offers “strong competitive advantages for those looking to offshore or outsource services,” particularly as a back-office centre for large corporates, banks and government agencies from the West. “This is relevant in a cyclical context with tighter labour markets and from a structural standpoint with an aging workforce in the western world,” he says.

Service-led companies in the ecommerce, transportation/logistics and fintech space might grow rapidly.

“If we are to forecast the most valued companies list for India in the next 10 years, at least two to three companies will be from the technology space in each sector,” says Vikram Vaidyanathan, managing director of Bengaluru-based Matrix Partners whose current investments include Ola Cabs, Practo, Razorpay and Quikr.

Moreover, “India can clearly create a company which can go global in the next decade,” Vaidyanathan says, a statement all the experts Forbes India spoke to agreed with. “The only caveat here is that they must conquer their local markets first similar to what Chinese companies have done,” Vaidyanathan says.

Last year, India added several more startups to its growing list of unicorns, including OYO Rooms, Paytm Mall, Freshworks, Byju’s, Swiggy and Zomato. The potential of these companies could be unleashed in a major way on a global scale in the next decade

First Published: May 13, 2019, 11:40

Subscribe Now