Going Long on Shorts

The rise in digital platforms and their ever-growing audience are enabling filmmakers to experiment with the short film format and take it beyond film festivals

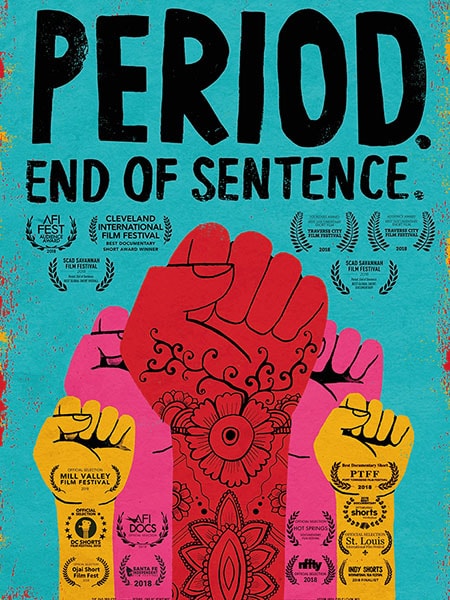

Guneet Monga, founder of Sikhya Entertainment, agreed to join the making of Period. End of Sentence. (below) after listening to the idea of the short film, which dealt with the taboos surrounding menstruation in India

Guneet Monga, founder of Sikhya Entertainment, agreed to join the making of Period. End of Sentence. (below) after listening to the idea of the short film, which dealt with the taboos surrounding menstruation in India

Image: Aditi Tailang

The first time Guneet Monga, founder of Sikhya Entertainment, a production house based out of Mumbai, got into the short documentary space was in 2016 when American film producer Stacey Sher reached out to her for a short film her daughter was making in India. After listening to the idea—a film about the taboo around menstruation and how social entrepreneur Arunachalam Muruganantham was making cheap sanitary pads—Monga decided to come on as executive producer of the film.[br]

The team hired a young director, Rayka Zehtabchi, who was fresh out of the USC School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles, to make the film. Their aim, when they started shooting at Hapur village in Uttar Pradesh, was to raise funds for a pad-making machine to donate to Muruganantham. Little did they know that the short film, Period. End of Sentence., would go on to bag the 2019 Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject).

Not just documentary and non-fiction, shorts, including in genres like thrillers, comedy, drama, horror and romance, are seeing a revival in recent years. While traditionally, they were considered only for film festivals, today they are finding an audience through YouTube, IGTV and over-the-top (OTT) platforms. They are attracting not just young and amateur filmmakers but also the biggest names in cinema the only requirement being a powerful script.

“Shorts are a quicker way to connect with the audience. Even a 5-minute film with a powerful story is going to connect with the audience,” says short filmmaker Satyarth Singh, who established his production house, Lights on Films, in 2012. He has made six to seven shorts, starting with a documentary in 2013 and moving on to fiction in 2014.

Shorts help filmmakers be bold, and narrate stories in a way they cannot on the big screen. “Creatively, it allows us to flex our muscles and what we cannot say in feature films, which are limiting and commercial and which have a certain kind of storytelling. Shorts allow you to go into uncharted territory,” says Monga. It is the filmmakers’ fearlessness, talking about what they really want to, that comes into play without them having to worry about commercial success.Shorts enable filmmakers to tackle taboos like menstruation, consent, sexuality and gender, thus helping in their normalisation.

The form has recently seen filmmakers like Sujoy Ghosh making Ahalya and Anukul Imtiaz Ali The Other Way, Perfect Strokes, and Bruno and Juliet Anurag Kashyap too has a host of shorts to his credit like That Day After Everyday and Last Train to Mahakali and along with Karan Johar, Zoya Akhtar, and Dibakar Banerjee, an anthology of four shorts in Bombay Talkies and Lust Stories.

Audiences get to see braver stories by mainstream filmmakers in a shorter span of time—a significant factor in the era of dwindling attention spans. About 15 years ago, only film fanatics were considered the audience for shorts at film festivals. Even until recently, with few other distribution channels or platforms, a major chunk of today’s audience was missing for shorts, says Singh. “When I made a short film in 2013, there was a small venue in Delhi called Iron Curtain that did alternative cinema screenings. It was either that or uploading the film on YouTube. There were no other channels, like OTT.”

Monga, who has produced over 50 shorts, attributes it to increasing mobile data usage. “It is the excitement around shorter content and digital stars that is helping the industry grow bigger. They are easily consumed and great stories pull people’s attention to the film.”

Ritam Bhatnagar is the founder of India Film Project, which runs a filmmaking contest

Ritam Bhatnagar is the founder of India Film Project, which runs a filmmaking contest

Image: Mayur Bhatt for Forbes India

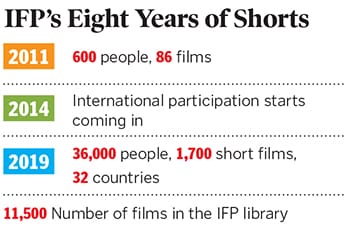

Shorts and small screens make for a perfect marriage, says Ritam Bhatnagar, founder of India Film Project (IFP), which runs an annual 50-hour filmmaking contest. “While people would turn to the TV to watch films for a longer duration, on mobile phones people can consume shorter content without having high expectations. And while watching only a part of a feature film while commuting can be infuriating, people can watch several shorts within the same time span,” says Bhatnagar who launched IFP in 2011. Its contest sees people come together to write, shoot, edit and upload a film under categories like professional, amateur, and mobile filmmaking. In 2016, IFP launched an annual two-day content festival, where aspiring storytellers get to meet film professionals and learn from the very best in the industry. Apart from digital distribution, the winning shorts are screened at PVR theatres across the country and every Sunday on MTV. Singh was among the top five at IFP in 2019 in the Professional Filmmaking Category.

For actors, too, the form allows them to tap into unexplored potential, says Monga. It has not only attracted veterans like Naseeruddin Shah, Jackie Shroff, Neena Gupta, Anupam Kher and Manoj Bajpayee, but also younger actors like Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Gul Panag , Radhika Apte and Alia Bhatt.

Sharanya Rajgopal, studio head of Terribly Tiny Talkies, says, “We work with a lot of veterans. For a very long time, they kept getting typecast into supporting roles in feature films. Here, we had an opportunity to feature stories of all genres, templates and subjects, where they were at the heart of each of these narratives.”

Terribly Tiny Tales, as an extension to their microfiction (writing stories in 140 characters), started Terribly Tiny Talkies as an experiment in 2015. The team asked 10 filmmakers to interpret the word ‘love’ and make a film that was under 5 minutes. After doing a similar project with the word ‘mother’, they decided to increase the time frame from 5 minutes in 2017.

Sharanya Rajgopal, studio head of Terribly Tiny Talkies, says short films provide a great opportunity to veteran actors

Sharanya Rajgopal, studio head of Terribly Tiny Talkies, says short films provide a great opportunity to veteran actors

Image: Aditi Tailang[br]

While feature films have a proper structure for a storyline, shorts generally start abruptly. They don’t take more than 30 seconds to establish a character, and the stories don’t require much establishment either. Characters in shorts are left to viewer perception, without talking in depth about their backgrounds. Shorts can’t introduce newer characters or multiple thoughts, as in the case of feature films, and have to start and end a plot within a very limited time. The shoot and editing work is wrapped up faster, so the story goes from scripting to being uploaded faster, as compared to feature films’ long shoots and theatrical releases.[br]

Unlike a feature film, which requires a big budget for sound, lighting, camera and crew, a short can be created by anyone who knows basic writing, shooting and editing, and has a phone. Monga, who has shot a few shorts on iPhones says, “It’s economical, it’s more powerful and gets into spaces where bigger cameras cannot. So, it’s very empowering.”

There are 2K and 4K resolution camera phones available at reasonable prices and filmmakers need to know only a few basic functions. A viewer on YouTube wouldn’t be able to differentiate between a video shot on a great camera phone and one shot on digital camera. Sometimes, you don’t even need a cast. Bhatnagar says, “At IFP, we have got short films where there’s not even a single person in front of the camera.”

Other variants include musical shorts, where there are hardly any dialogues and a story is delivered through video backed by powerful songs. These videos, generally spanning not more than 5 minutes, owe their success to a twist at the end of the video.

Advertisements, too, are going beyond 30 seconds and making short films to connect with consumers. Brands like British Airways, Cello, LG, HelpAge India and Urban Ladder have leveraged the emotional quotient to deliver advertisement shorts.

Rajgopal believes a film should be considered a short only when the filmmaker is convinced that it cannot be anything but. “If a film can be made into a short, a web show or a feature, we think we aren’t doing justice to the medium we are trying to engage our audience with,” she says. It’s something that comes with experience. “Whether a plot is worthy of a short or a feature film is something you know only after gaining experience in the industry,” says Monga.

Though shorts have come a long way, distribution still remains a problem. Bhatnagar says, “If you put a short film on a channel with millions of subscribers, even a mediocre short film will get a million views. When a creator puts out a very good short film through his own channel, it might only get views from friends.”

[qt]Even a 5-minute film with a powerful story is going to connect with the audience.

Satyarth Singh, Founder, Lights on Films[/qt]

Producers too are not keen on investing in short films. While they see a straight-up return for web series and feature films, the same is not true for shorts. So most end up being self-funded, helping a filmmaker establish a portfolio that could lead to bigger deals, advertisements and video projects. Singh, whose Piyush Mishra-starrer Sangharsh was put online on humaramovie says, “I do a lot of commercial work and from that I take out a budget to do my own films.” If the creator is then able to sell it to a distributor, such as LargeShortFilms, humaramovie, Six Sigma Films or Pocket Films, there might be returns.

But the potential for shorts in India seems immense. While there are a few roadblocks like distribution and the lack of business models, industry experts believe India will be able to crack these in the coming years and producers will start investing. “The audience is ever-growing. What we might see are a growing number of short makers as well as a rise in regional-language shorts,” says Bhatnagar.

Besides, the idea of a viral video has also changed completely. Rajgopal says, “I am really scared because I still don’t know how to use TikTok. That’s the new grammar, that’s the new syntax that is how people are talking.”

Bhatnagar adds, “People in tier II and III cities have already started making TikTok videos. They are a little more familiar with making videos. We’ll see someone make a good film out of them.”

First Published: Dec 28, 2019, 09:13

Subscribe Now