Inox: The wind beneath its wings

From industrial oxygen to refrigerant gases, chemicals to cinema exhibition, the Inox Group has diversified its portfolio over the last five decades. Now, its future growth hinges on the wind energy b

Sometimes the end determines the means. Ask 86-year-old Devendra Jain. Five decades ago, he set a simple goal for himself: Like many others in the Marwari community, he was intent on becoming an industrialist. That decided, he just had to figure out the ‘how’.

This was in the early 1960s—the Licence Raj was still upon India. The young Jain, a freshly-minted history honours graduate from Delhi’s St Stephen’s College, did not see himself joining his father Siddhomal’s successful paper trading business. Instead, he scouted for big business and landed upon the idea of extracting, liquefying and selling gases from air through a friend’s relative who worked at British Oxygen (now called BOC). Industrial gases were widely used in steel and manufacturing industries as well as in the health care sector and, more significantly, yielded high margins. He was sold. All he needed to do was understand the business from close quarters. He teamed up with his brother Lalit, travelled to Germany and the US, visited companies already in the business and bought an oxygen plant from Germany for its first unit at Pune in 1963.

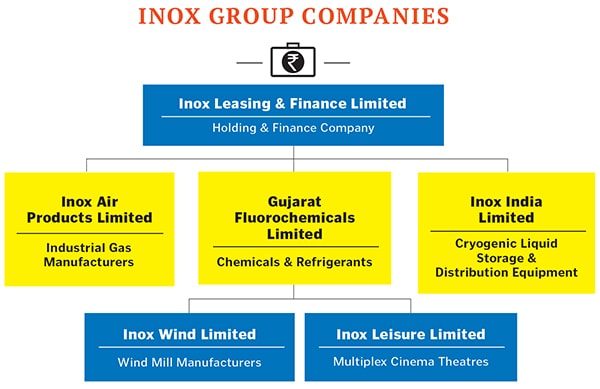

It was the beginning of Industrial Oxygen, which, as the name suggests, focussed on producing oxygen. More than five decades later, it is clear that Devendra Jain’s ambitions with gases have been built on solid foundation. His family’s over two billion dollar-Inox Group today runs six different businesses—and owes much of it to natural air. (He ranks 71 on the 2014 Forbes India Rich List and at last count, had a fortune of $1.41 billion.)

While the genesis of this empire can be traced back to Industrial Oxygen (now called Inox Air Products), its future is linked to its bet on wind energy, Inox Wind, which is expected to bring in half the group’s revenues by the next two years. The wind energy solutions venture is being spearheaded by Devendra’s grandson, 28-year-old Devansh, the youngest member of the Jain family to hold a position in the Inox Group. Devansh is buoyed by the success of the company’s initial public offering.

Its recent (March 18) Rs 1,000-crore public issue witnessed 18 times more subscription than the shares on offer. The stock listed on April 9 at Rs 400, a 23 percent premium to its offer price, indicating that at least initially, the markets had taken a favourable view of the company.Consider though, that a decade ago, neither Devansh nor his father Vivek Jain, who is managing director of Inox Group’s Gujarat Fluorochemicals Limited (GFL), or his uncle Pavan (chairman and MD, Inox Air Products), had any prior experience in renewable energy. But in a manner similar to Devendra Jain’s determination to understand the gas business all those years ago, they rolled up their sleeves and began studying the wind business. “Due to our exposure to the carbon credit business, we were aware of international political negotiations around climate change. The first strategic response to that was renewable energy, for which there is always a demand in India given the energy deficit,” says Devansh. “Secondly, when we looked at the business, we saw that the mix of renewable energy was fairly low, like four to five percent, but growth was projected to be at a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 25-27 percent. We thought it was a fairly good opportunity to get into, and started with the wind-farming side of the business.” (Over the last 21 years, wind power capacity addition in India has taken place at a CAGR of 32.87 percent from a modest installed capacity base of 54 MW in 1993 to 21.1 GW by 2014. The CAGR over the 10th and 11th Five Year Plan periods was 26.64 percent.)

The more they researched the sector, the more the Jains were convinced about investing in the wind business. In 2009, they decided to launch Inox Wind. “When we entered the wind market, large players like Suzlon were suffering losses. But we knew that it was possible to make a difference. We got the best technology and set up a manufacturing plant (in Rohika near Ahmedabad, Gujarat), and today our operating cost at the wind turbine plant might be the lowest in the world, while operating margins are the best in the world,” says Pavan, 63.

This success, however, came after many ‘learnings’. Around 2007, Devansh was getting ready to join the group, having majored in economics at Carnegie Mellon University in the US. Under the guidance of senior family members, he bought wind farms from Vestas and Suzlon to learn the ropes of the wind business. Needless to say, it was a steep learning curve for the youngest Jain. From the word go, he had to sort out problems related to wind power generation capabilities of turbines as well as understand the importance of conducting accurate wind assessment for each project, and also the efficiency of the wind mill blades. This experience taught him how not to do the business. “We learnt the pitfalls in this business and soon realised that we needed to make our own blades, assemble our own turbines and build a land bank to enable us to become a turnkey solutions provider,” says Devansh, who is director at Inox Wind.

In April 2009, Inox Wind inked a deal to buy technology know-how and design for wind turbines and blades from AMSC Windtec (in Massachusetts) and Germany’s WINDnovation GmbH. Soon the company built its first turbine at its Rohika plant. “We made initial prototypes of our own turbines and blades, installed them, underwent the entire certifications cycle and in 2011, we got certified (by authorised agencies). Our first wind farm was ready, and from the middle of 2012, we entered the market to sell turbines and complete turnkey projects,” says Devansh, who points out that he learnt the ropes of the business with each setback.

Apart from manufacturing turbines—Inox Wind has plants in Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh—the company also builds wind farms, generates power and sells completed projects to customers. It had an installed capacity of 330 MW of wind energy last year, and key clients included the Goldman Sachs-funded ReNew Power, the Morgan Stanley-backed Continuum Wind Energy and Tata Power. With an order book of about 1,258 MW, it is slated to earn revenues of over Rs 6,000 crore by March 2016, that is, once the projects are commissioned. It is estimated to end 2015 at Rs 3,200 crore.

Says Ravi Shenoy, VP (research analyst–midcap) at Motilal Oswal Securities: “Inox Wind has a healthy order book. It has executed some projects well, so the momentum is with them. The IPO fared well because Suzlon Energy, at present, is not in the best state. People want something on the alternative energy side and this is the best bet.” That said, Inox Wind is still a new player when compared with market leader Suzlon Energy, which recently sold a 23 percent stake to Sun Pharmaceutical’s Dilip Shanghvi for Rs 1800 crore.

Shenoy believes that wind is a significant space given the government’s recent focus on the renewable energy sector. Earlier this year, the government of India set a target of installing 60 Gigawatts of wind energy plants by 2022. “Historically renewable energy has been more used for tax breaks due to the AD (accelerated depreciation) policy and depreciation of 100 percent in the first year. However, now companies want to be seen as going green and the easiest way to do that is to set up wind farms, to meet the requirement,” Shenoy says.

Not all are buying into this new bullishness, though. Energy expert Amit Bhandari has his reservations about the wind energy sector, especially because there is a dearth of wind-efficient land needed to install wind farms. “The best sites would have been taken, and new wind farms won’t come up on a very large scale in the near future,” says Bhandari, who is a fellow (energy & environment studies) at the Mumbai-based non-profit think tank, Gateway House. There is another reason for his cautiousness: Most wind farms don’t operate at more than 20 percent of their capacity due to intermittent wind conditions. “So the capital cost of wind energy is about four times that of coal for generating the same amount of energy. So it’s a fairly expensive form of energy,” he says.

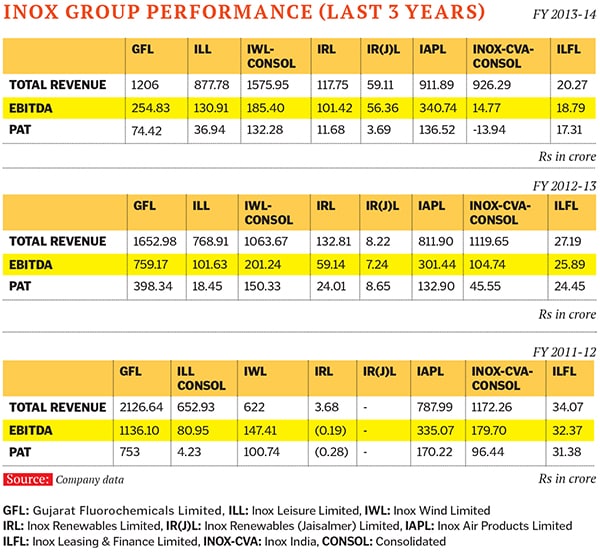

For now though, it is full steam ahead for Inox Wind. It is already the group’s largest company (by topline), with Rs 1,575 crore worth of sales and profits of Rs 132 crore as of March 2014. But as wind energy gets touted as the future of this group, its success has roots in the past. Built on air

Built on air

The path to this windfall has involved judicious risk-taking, though the Jains insist that they have always erred on the side of caution. The inarguable fact is that the family has managed to not only adapt, but also thrive in tough situations.

By the late ’80s, under the guidance of Pavan (an alumnus of IIT-Delhi) and Vivek (a Stephanian, like his father, and an IIM-Ahmedabad graduate), Industrial Oxygen was also producing gases such as hydrogen, carbon-dioxide and helium, to name a few. It had expanded its reach and bolstered its customer base to include pharmaceutical industries and hospitals that need medical oxygen for patients.

In 1991, just a year after Devendra and his sons Pavan and Vivek (59)—who by then had joined their father’s business—went public with Industrial Oxygen, the Indian economy had opened up. Soon enough, global companies began entering India due to the potential it offered them.

But international companies were now challenging this homegrown business, both on price points as well as on the latest technology needed to produce gases efficiently.

The Jains realised that to fight behemoths like The Linde Group, Praxair and Air Liquide, they needed to have access to capital and invest continuously in research and development. They delisted the company from the stock market and partnered with Air Products (USA), which bought a 50 percent stake in 1999. Industrial Oxygen became Inox Air Products, and today, it claims to have the largest market share (35 percent) in India.

The partnership between the two companies was further strengthened when Pavan’s son Siddharth, a mechanical engineer from the University of Michigan, did a stint at Air Products in the US. He returned to India and joined Inox Air Products in 2002, and has been instrumental in its growth. Revenues have risen by 257 percent from Rs 255 crore in 2004 to Rs 911 crore by 2014.

Industry analysts estimate a turnover of Rs 1,150 crore, and Ebitda (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) of about Rs 495 crore by the end of March 2015. “It is a steady business with good Ebitda margins. Increasing use of gases in the food and health care sectors and the fact that manufacturing will pick up pace with the ‘Make in India’ campaign… means the business has great scope ahead,” says Pavan.

His son Siddharth (36), who is whole-time director at Inox Air Products, espouses the family’s motto of slow, steady and safe growth. “Mindless expansion is not part of the plan. My grandfather (Devendra Jain) always says that safe growth is better than leapfrogging into debt. We don’t believe in overleveraging ourselves,” says Siddharth. Pavan and Vivek may be conservative players when it comes to debt, but the brothers have never been wary of taking bets on new businesses if they spot an opportunity. “We have the ability to take risks, but never to the point of absurdity. We have never shied away from entering unchartered waters,” says Pavan.

This work ethic held the family in good stead during the trying years at the turn of the century, when one of their key businesses was under threat.

Profit in travesty

In the ’80s, the two brothers helped lay the foundation for Inox India, now one of the largest manufacturers of cryogenic tanks in the country. But even as they were doing that, Vivek and Pavan realised that they were in a good position to expand into the refrigerants business. Sales of refrigerators were already increasing, and the Jains rightly predicted that air-conditioners would follow soon. Manufacturing refrigerants like chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) was a logical extension to their existing gas businesses. Vivek took the lead and set up GFL in 1989 at Panchmahal, Gujarat. (He is currently GFL’s managing director.)

By leveraging the manufacturing and technical skills of Inox India, they used disposable cylinders to export refrigerant gases. “At the time, we were the only company in India to not just make refrigerant gas but also produce the required cylinders. Our competitors had to import cylinders so they did not have the logistical and cost advantage that we had,” says Deepak Asher, director and group head of corporate finance at GFL.

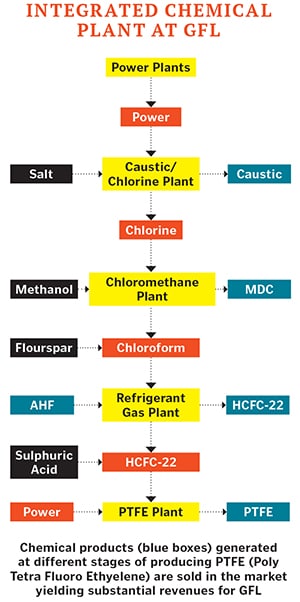

But ten years later, GFL’s future was bleak: In 2000, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer mandated that developed countries reduce the consumption and usage of CFC, eliminating it completely by 2010. Vivek and Pavan had to figure out how to grow a business when its core product was being banned internationally. They quickly began moving CFC production to HCFC-22, a refrigerant gas, which was on the permissible list back then. But its production resulted in the generation of a byproduct, HFC-23, later identified as a greenhouse gas that contributed to climate change. Though this gas is benign at the ground level, it causes global warming when released into the atmosphere. In the air, the impact of a tonne of HFC-23 is said to be equivalent to that of 12,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide. GFL’s factory in Gujarat had a capacity of producing 25,000 tonnes of HCFC-22 and releasing 750 tonnes of HFC-23 into the air.

By 2005, the Kyoto Protocol, which mandated that developed nations reduce the production of greenhouse gases like HFC-23, came into effect. Emerging economies like India did not have to comply with these stringent norms, but it was only a matter of time, and the Jains were well aware of that. Under the Kyoto Protocol, companies can earn carbon credits by voluntarily reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which they can trade with corporations and businesses that are unable to meet the new norms.

The management at GFL recognised the potential of a windfall here. They did not hesitate to invest in a new technology to incinerate HFC-23 instead of releasing it in the air and earned carbon credits in the bargain. In 2006, GFL was the first Indian company to get approval from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

By reducing its HFC-23 emissions drastically, GFL earned a total of 55 million carbon credits by 2012, earning about Rs 3,400 crore, according to a June 2014 analyst report by Anand Rathi Research. The profit earned was used to strengthen the chemical business at GFL, and of course, invest in new sectors. “We have also been lucky, in all modesty, and fortunate to be in the fluorochemical business, which led to the carbon credits benefit,” says Pavan.

While it may have started as a refrigerant manufacturer, GFL, which is also the holding company of Inox Wind, now has a substantial chemicals business that has an integrated PTFE plant. (See box)

Instead of distributing profit from carbon credits as dividends to shareholders, the Inox Group decided to explore new arenas. And in more ways than one, the profits earned from carbon credits and the success of GFL helped strengthen not just the wind foray, but also the conglomerate’s leisure business. “The money we earned in carbon credits was prudently deployed in the wind, chemical and even the movie business,” says Pavan.

An unusual bet on movies

Though GFL turned out to be a jackpot, the Jains, afflicted by the same bug that bit a young Devendra more than 50 years ago, were restless. In 2002, Pavan and Vivek decided to start a new line of business to hedge against the threat posed by the phasing out of the CFC business. With a thoroughness that friends and employees have come to recognise, the brothers consulted McKinsey & Co to survey different businesses. The Jains studied a hundred different business plans and assessed various sectors before deciding to invest in a multiplex cinema chain and enter the film exhibition business by setting up Inox Leisure Ltd.

Multiplexes make strange bedfellows for the refrigerants, gas extraction and wind energy businesseses, but Inox Group straddles these different sectors with ease. And there was a method to the Jains’ plans.

According to Deepak Asher, who is also the founder and president of the Multiplex Association of India, at the turn of the century, there were 9,000 single screens in the country. There was a strong case for starting a multiplex chain, given that India is a very large film market with 600 regional language films, 200 Hindi movies and 200 international imports.

“With a population of a billion people wanting to watch movies, five billion tickets are sold every year today, it’s the biggest in the world,” says Asher, justfying the move into movies. About 2,000 multiplex screens bring in 70 percent of the movie revenues, while the balance 7,000 single screens get 30 percent of the box office collections. Inox Leisure started with two multiplexes, one each in Pune and Vadodara, both cities where they had their chemicals and gas business. The Jains paced their expansion with the option to pull out if and when required. This business decision proved to be a prudent one, and Inox Leisure grew with the Indian economy. In 2003, the group invested Rs 59 crore to start one of their most profitable properties in CR2 mall at Nariman Point in South Mumbai. Today, the chain has 94 properties with 365 screens across India. This has been achieved on the back of three acquisitions—Calcutta Cine in 2006, the Fame multiplex chain in 2010 and Satyam Cinemas in 2014.

Inox Leisure controls 10 percent of the country’s box office revenues, but the largest multiplex chain in the country is PVR. Of course, the Jains aren’t quite happy with this, and have the war chest ready for more acquisitions in the race to become number one. While it may not be the market leader, it is in a comfortable position. Over the last four years, its revenues have grown from Rs 256 crore in 2010 to Rs 870 crore in 2014, with a growth of 37 percent per annum (topline). Analysts estimate that it will cross Rs 1,000 crore by FY15 with an Ebitda of Rs 135 crore, and a CAGR of 28 percent.

The cinema chain business is the only B2C (business to consumer) model that the group has currently, and Siddharth Jain, who has direct oversight on it, says it lends the family an opportunity to explore more such consumer-facing businesses in the future. “We sell 4.5 crore tickets at Inox Leisure across India, while the aviation sector in India sells five crore tickets per annum. So we have 4.5 crore touch points with our consumers, which can be leveraged to do something in the consumer space,” says Siddharth, who shares his grandfather’s enthusiasm for exploring new markets.

Pavan adds: “Today, the Inox Group, which has an approximate turnover of Rs 5,400 crore (FY14) has the potential to touch Rs 20,000 crore in the next five years if it continues to grow at the current rate.” It would be hard to predict what the Jains will invest in next, but what is assured is a measured approach to expansion. And that the end will, invariably, justify the means.

First Published: Apr 29, 2015, 07:07

Subscribe Now