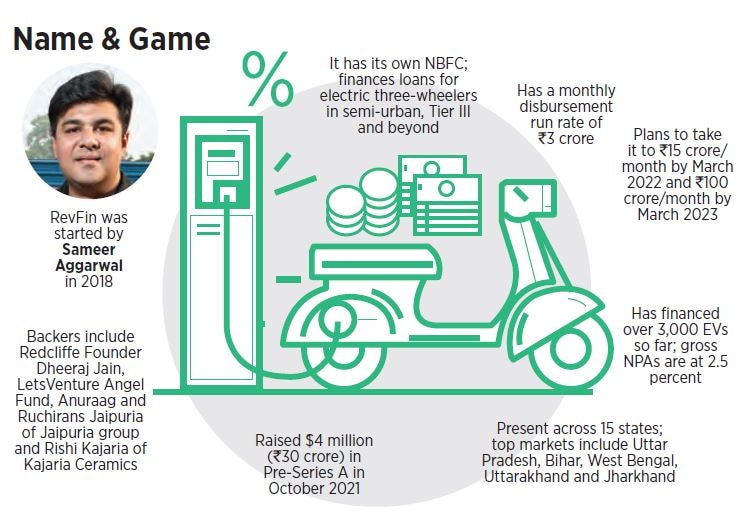

How banker-turned-investor Sameer Aggarwal is financing the EV revolution

Former HSBC banker Sameer Aggarwal has been a prime mover in financing electric rickshaws with RevFin. Will the gambit pay off?

Sameer Aggarwal’s tryst with ‘prime’ started early. He graduated from IIT Kharagpur—one of the top engineering colleges—in 2006 his maiden job was with HSBC, and after a few years, the Delhi lad relocated to London and continued to work with one of the world’s largest financial and banking organisations. His almost-decade-long stint was dotted with prime roles such as managing £20-billion portfolio comprising credit cards, personal loans and overdrafts, handling credit risk for retail assets globally, and working across six continents in 15 countries.

In 2015, he quit his job. Though keen to start his own venture, Aggarwal wanted to check his appetite for a startup life full of hustle. “I wanted to check whether I am still a corporate guy or do I have it in me to take a solo plunge," he recalls.

The second innings started on a ‘subprime’ note. Aggarwal joined London-based subprime lending startup Oakam. As head of risk and analytics for two years, he gained rich insights into the financial lives of the underbanked, the ones without any credit history and the ones having a broken track record of repayments. “From prime I moved into subprime, and it was an enriching experience," he recounts. The stint also prepared him to start his entrepreneurial journey. “It was clear that I wanted to do something in the financial segment," he says. “But I didn’t know what. There was a lot to explore." Towards the end of 2017, he came back to India.

After a few months of brainstorming, Aggarwal bumped into an electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer. “It was serendipity," he recalls. It was October, Delhi was gradually getting chocked due to the annual ritual of stubble burning by farmers across Delhi-NCR, Haryana and Punjab, and the air was already oppressive due to heavy vehicular emissions. “Why don’t you start financing electric three-wheelers?" the visitor nudged Aggarwal, who was sitting in his one-room office in Central Delhi. “They cost around ₹1.5 lakh, and the headroom for growth is massive," he underlined.

The idea sounded electrifying. “It was good for the environment," Aggarwal reasoned. “But was it good business?" The former banker just needed one set of data to take the call. Back then, there were around 20 lakh electric three-wheelers on road in India. What was glaringly missing, though, was just one thing: Organised lending player. Aggarwal decided to be a prime mover, and started RevFin, a digital financing platform for electric three-wheelers in 2018.

The beginning was slow: One loan a day. But after six months, the business gathered pace: Three loans a day. RevFin quickly spread across 15 states and Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Uttarakhand and Jharkhand emerged as its top markets. “Before March 2020, we were doing 10 loans a day," recalls Aggarwal, who raised $4 million (about ₹30 crore) in a pre-Series A round of funding in October from a clutch of backers, including Redcliffe founder Dheeraj Jain, LetsVenture Angel Fund, Anuraag and Ruchirans Jaipuria of Jaipuria group and Rishi Kajaria of Kajaria Ceramics.

A year-and-a-half post the national lockdown, the business is galloping at an electric pace. RevFin has a monthly disbursement run-rate of ₹3 crore, and is on track to take it to ₹15 crore per month by March next year. “By March 2023, we plan to disburse ₹100 crore per month," says Aggarwal, adding that the startup has financed over 3,000 EVs so far, and claims to have a gross NPA (non-performing assets) at 2.5 percent. “Before the pandemic, there was not even a single case of default," he informs. Though some of the borrowers—mostly daily wage earners—missed their EMIs due to zero work during the lockdown, others managed to exhibit fiscal discipline.

Backers of RevFin are elated with the performance. “They have quickly built a financing network in over 100 small towns with near-zero customer acquisition cost," claims Dheeraj Jain, founder of Redcliffe Life Diagnostics. Commercial EVs, he says, provide much better cost of ownership to drivers compared to ICE (internal combustion engine)-based vehicles using petrol and diesel. “Most ecommerce companies too have made commitment to switch their fleet to electric," Jain says, adding that a combination of better economics and sustainability makes a compelling case for high EV adoption in the country.

India has over six million [60 lakh] three-wheelers on road, and the government plans to convert a chunk of them into EVs. “Electric mobility adoption is on the cusp of a revolution in India," he says.

Aggarwal, though, wants to talk about a different kind of revolution that RevFin is part of. “Over 90 percent of our users are new to credit. They do not have any loan history," he says. Most of the customers, he explains, are daily-wage earners and owning an EV gives them an opportunity to make more money than driving any other mode of mobility. In the absence of any formal lending mechanism, most potential borrowers end up taking money from unorganised private lenders. In January, Revfin received funding from Shell Foundation in partnership with electric vehicle operator SmartE to accelerate adoption of electric mobility solutions among the low-income consumers from Tier II cities of eastern Uttar Pradesh.

There is another reason why India is primed to see electric rickshaws across the country over the next few years. “Still in a lot of small towns, there is no concept of last-mile passenger mobility," Aggarwal says. “Electric rickshaws are the answers, and that’s why we see a huge opportunity there."

Can aggressive lending to a segment which does not have any credit exposure turn out to be a potential challenge for the startup? Aggarwal reckons two factors have ensured that RevFin’s bets are hedged. First, all loans are secured loans. The vehicles are hypothecated to the startup. Second is the element of pride and shame. “For daily-wage earners, it is a matter of pride to own a vehicle," he says. They do not want to get rid of it as it generates a decent source of income. And for defaulters, the shame element is when loan collectors knock on your doors for recovery.

RevFin is also planning to add more revenue engines. While it will expand its core business of financing electric three-wheelers by collaborating with OEMs (original equipment manufacturers), dealers and point-of-sale finance, it will also deepen its footprint across 16 states. The new business opportunity comes in ecommerce delivery business.

Aggarwal explains that as the Swiggys and Amazons of the world move into converting their fleet to electric, RevFin has started partnering with fleet operators who manage operations for ecommerce players. This business model, he says, would be more focussed on big cities rather than small towns, and will also include electric two-wheelers and e-autos. “By October next year, about half of our business will come from this vertical," he says, adding that over the next few years, ecommerce has the potential to become the main source of revenue. RevFin, he claims, is clocking an annualised revenue run rate of ₹7 crore, and is targeting a three-fold jump over the next fiscal. “Our next target is ₹25 crore, and then ₹75 crore," he says, adding that the biggest challenge for the startup is to stay focussed and stay aggressive.

What Aggarwal should remember, though, is that displaying too much aggression in lending business—whether prime or subprime—carries with it an inherent warning: Shock and awe.

First Published: Nov 22, 2021, 13:10

Subscribe Now