The hands that pull the strings

Can modern puppeteers in India help breathe new life into a centuries-old, dwindling tradition?

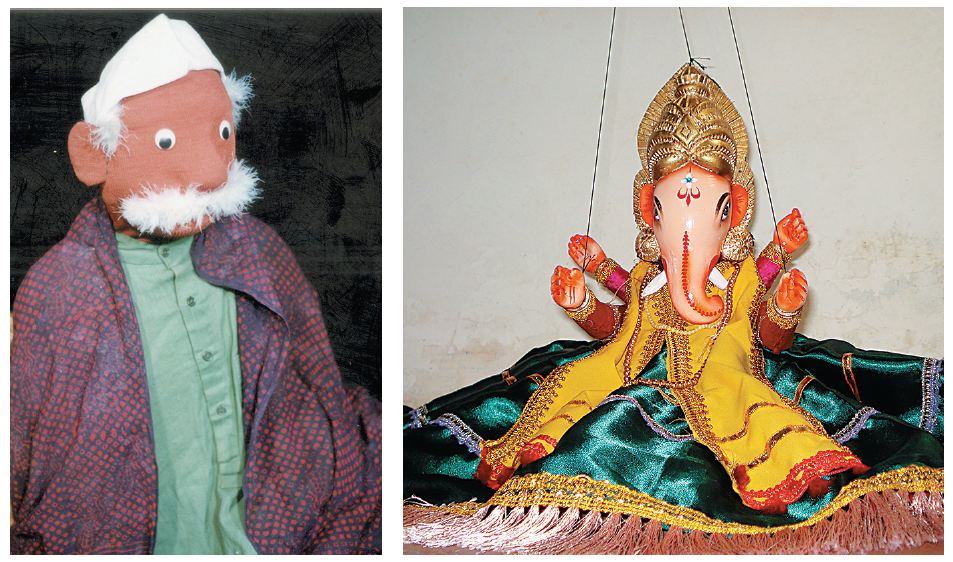

Bengaluru-based Dhaatu Puppets’ stories are largely based on the epics

Bengaluru-based Dhaatu Puppets’ stories are largely based on the epics

Image: Anupama HoskereAnurupa Roy has a tendency of holding her audience in thrall. Whether she is performing at a Junoon Salon event in Mumbai, or the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, or the Joburg Theatre in Johannesburg, Roy’s audience watches mesmerised as episodes of the Mahabharata unfold on stage. What makes it so captivating is not such much as the story—we all know how it ends—but the manner in which it is brought to life... through the dead material of puppets.

Roy’s puppets range from the pint- to human- to giant-sized. They wear masks that indicate different characters, or characteristics they ride on the shoulders of humans, wrestle with them, or fall in love. On the darkened stage of auditoriums, where the largely urbane crowd sits in hushed silence, the accompanying music and light—sophisticated in their composition and implementation—add the drama, pathos or joy to the unfolding narrative.

And then there is Ranjan Ray. A puppeteer since 1968, who took to the art form because it seemed to be a viable way of making a living in the poverty-stricken district of Nadia, in West Bengal, where other forms of livelihood were difficult to come by. Armed with his bunch of string puppets, Ray travels throughout Bengal—and as far as Delhi, and Thane (Mumbai’s neighbouring district)—with stories from the epics, folk tales and some of his own. (Left) A performance of Anurupa Roy’s Mahabharata (right) Ranjay Ray’s Radha Krishna puppets have travelled beyond West Bengal

(Left) A performance of Anurupa Roy’s Mahabharata (right) Ranjay Ray’s Radha Krishna puppets have travelled beyond West Bengal

Image: Anurupa Roy (Left) Ranjan RayPerforming at all times of the day, in the midst of noisy village fairs, puppet festivals—such as the one in Nadia’s Muragachha Colony—or the recently-concluded Sur Jahan World Peace Music Festival in Kolkata, Ray’s is an art inherited and learnt from one generation to the next. What has changed over the years are some of the materials he uses to make the puppets, and some of the stories he tells. What has not changed much is the modest position their puppetry holds amid the more haloed forms of performance arts, and hence their economic and social conditions.

Roy and Ray represent the two realities of puppetry in India: While one has trained with the best in India and abroad and is highly influenced by practices in foreign countries, the other carries forward a tradition that is so old that it is difficult to ascertain where and how it started while one is finding an audience with an urban, even global, population that views puppetry as a novel and intriguing form of performing art, the other finds limited exposure to fresh ideas, and is struggling to find takers, even amidst its own population that is perhaps tiring of the art form and moving to regular jobs that hold better economic promises.

******

The two starkly different realities of puppetry in India—which, by some accounts, is where the art form was born, before spreading to other Asian countries, such as Indonesia and Japan, and then to Europe—can, in some measure, be attributed to the fact that despite it being such an ancient tradition, there have been no formal institutions, infrastructure and pedagogy for it. Recognised by the government only as a folk art, it has been left to the traditional practitioners themselves—who came from marginalised populations such as tribals—to hand it down from one generation to the next simply as a means of eking out a living.

Chetan Gangavane is the latest in the line of chitrakathis—communities who make a living by narrating tales, accompanied by handpainted pictures on paper—in the Pinguli village of Maharashtra’s Sindhudurg district. “We tell stories from the Ramayana based on paintings that we make on handmade paper,” says Gangavane, who studied for a diploma in engineering in Kolhapur, and then gave up his job in Mumbai to return to his village in 2007 to revive a tradition that he traces back to at least 350 years. “In the whole state, ours is the last family that practises this art form. We come from the tribal community of Thakars, and have 11 traditional art forms that include handicrafts and performances.”

Gangavane adds that although there is no documentary proof, mention of their puppetry forms are found in ancient texts such as the Dnyaneshwari of the 13th century, written by Marathi saint and poet Dnyaneshwar. In the small museum—Thakar Adivasi Kala Angan (Museum and Art Gallery)—that his father, Parshuram Gangavane, established in their home in 2006, there is paper that can be traced back to the East India Company, dating back to about 300 years. “When our ancestors lived in the jungles, they made their paintings on large leaves. Shivaji maharaj introduced us to paper,” he adds. “During his times, puppeteers would also serve as detectives, since we could gather information from different parts of the kingdom when we travelled.”

Over the many generations, the community imbibed forms of storytelling other than chitrakathi. These include the kalsutri bahulya, a string marionette show depicting stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata the dayati, or shadow puppet theatre and the pangul bael, a ritual form of theatre around the figure of the sacred bull of Shiva.

Similar in tradition and circumstances are the stories of West Bengal’s puppeteers, such as Ray of Nadia and Basanta Kumar Ghorai of Purba Medinipur district. There are three popular forms of putul naach (literally, doll’s dance) in the state—dang (rod), beni (glove) and taar (string). Ray performs with string puppets, while Ghorai with glove puppets, probably the oldest of the three forms.

“We took to puppetry because we were very poor, and saw others making some kind of a living through these performances,” says Ray. “We would go from one village to the other with our dolls.” Ghorai, in a demonstration at the 8th India Puppetry Festival organised by the Sangeet Natak Academy in Delhi in 2016, said this art form has traditionally been associated with begging. “When people did not want us to come to their homes any more, they would set their dogs upon us,” he remembers.

It is only through some government initiatives and schemes—West Bengal is one of the few states in India that supports puppetry—that Ghorai learnt how to make puppets that were lighter, and therefore less painful, to handle: “When my father and uncles performed, the heads of the glove puppets were made of terracotta, and the hands of chiselled wood. But then we learnt how to use papier-mâché. Now the puppets are lighter, and easier to hold.”

Ray’s and Ghorai’s travels to Kolkata, Delhi and other cities also made them aware that continuing with the age-old stories they have inherited may not be enough to engage new-age audiences who have other forms of entertainment. “We have adapted our stories, and now talk about social issues that we see around us,” says Ray, who has established the Sree Ma Putul Natya Samaj. “We often raise awareness, through government campaigns, about things such as child marriage, and human trafficking.” To make it a medium of mass entertainment puppetry also draws inspiration from popular Bengali films, such as the 2007 Mithun Chakraborty-starrer Minister Fatakeshto.“Tradition is not something that is static,” says Anupama Hoskere, a classical puppeteer, and founder of Dhaatu Puppets in Bengaluru. “It is constantly evolving by imbibing ideas and influences from elsewhere.” She, however, laments that traditional puppetry in India has stagnated over the decades and become corrupted in its form. “Generational puppeteers often follow tradition without knowing or understanding the reason and logic behind their traditions. We, at Dhaatu, are classical puppeteers because not only do we follow traditions, but also understand them.”

Hoskere, a Bharatnatyam artiste and an engineer by training, combines her learnings from both fields into puppetry, and has trained under Karnataka’s master gombeyata (rod) puppeteer MR Ranganatha Rao, as well as in the Czech Republic. The stories that she narrates through her performances are largely based on the epics and Puranas.

******

Hoskere is perhaps a bit of an exception in that she is not a generational puppeteer and yet is a traditional one. Other contemporary puppeteers are keen on relatively modern forms of the art that is influenced by foreign training and exposure. Hoskere mentions the various puppet theatre festivals that take place around the country, among which those in Bengal and Kerala include traditional forms. “Most of the other festivals are more inclined towards modern puppetry forms,” she says.

The Ishara International Puppet Theatre Festival, now in its 17th year, for instance, has participants from countries as varied as Brazil, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, the UK, Italy, Tunisia, Iran and Afghanistan. The Dhaatu International Puppet Festival, which started in 2009 with 20 participants from Karnataka, has expanded to include more than 100 participants from across the world. “What is most heartening is that traditional puppeteers from India who had come to our festival in the early years have evolved over the years as they have realised the gamut of their art form and its capacity, and have discovered a new audience,” says Hoskere.

Festivals provide a much-needed platform for traditional puppeteers, who, otherwise have little or no support from the government. Commenting on government policies and attitudes towards puppetry, Ranjana Pandey, puppeteer, playwright, theatre and television director, says, “When you have Bharatnatyam at the top of the hierarchy of performance arts in India, there is very little chance for puppetry that stands at the bottom of the ladder. It is relegated to the status of folk art and has never received the attention, support and sponsorship that it has got in countries like Indonesia and Japan, where it has been elevated to a fine art.” (Left) Ranjana Pandey’s puppets have found their way to television (Right) A Chetan Gangavane string puppet. Gangavane revived a tradition dating back 350 years

(Left) Ranjana Pandey’s puppets have found their way to television (Right) A Chetan Gangavane string puppet. Gangavane revived a tradition dating back 350 years

Image: Ranjana Pandey (Left) Chetan Gangavane “Traditional puppeteers are struggling, as audience tastes change. So for them it is a question of ‘abandon or adapt’,” says Pandey. “But we have to remember that this is not the first time they are facing this dilemma, and creativity can take them a long way.” The perception of patrons and audiences in the future will depend on the quality of the performance, she adds.

The lack of government recognition is what pushed puppeteer Meena Naik to start a four-month certificate course at the Mumbai University in 2012. Since she is primarily focussed on issues related to children, her course attracts educationists, teachers, psychologists and other experts who deal with similar issues, and use puppets to raise awareness among children or help them deal with difficulties. “We work with traditional techniques—such as shadow, glove, rod and strings puppets—but use contemporary materials such as plastic and foam,” says Naik.

“Traditional puppeteers would perform only stories from the epics and folk stories, and were rather rigid in their formats and lengths of performances,” she says. “But now they are adapting, and have narratives dealing with raising awareness about different societal issues and government campaigns.”

******

One of the earliest modern puppeteers in India was Meher Contractor, who was trained in London and whose contributions and style continue to influence newer generations. Contractor’s work at the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts in Ahmedabad nurtured several new puppeteers who went on to become veterans of the field, including Mahipat Kavi, Bela Shodhan, Mansingh Zala, Dadi Pudumjee and Ratnamala Nori.

“Urban puppetry has been highly influenced by the West, with mega performances in countries like the US, South Africa and Japan, and has inspired the younger generation in India,” says Pandey, who trained in Belgium. The Unima India Foundation Course for Puppeteers includes classroom teachings on sculptures, puppet-making, story building and manipulation techniques

The Unima India Foundation Course for Puppeteers includes classroom teachings on sculptures, puppet-making, story building and manipulation techniques

Image: Anurupa Roy“Pudumjee set the precedence for contemporary puppeteers by breaking a lot of norms,” says Anurupa Roy, while speaking of the founder of the 30-year-old Ishara Puppet Theatre Trust, and president of the Union Internationale de la Marionnette (Unima, or the International Puppetry Association), based in Prague. Pudumjee and his group include non-puppet elements, such as dancers, actors and objects, in their productions, and borrow from various traditional Indian forms, as well as global practices. “Dadi has a distinct style,” adds Roy, who was trained in Sweden, Italy and the Netherlands. “It took me years to find my style, and I am still not sure if I actually have one.”

This ‘style’ that contemporary puppeteers need to create for themselves, is something that generational puppeteers inherit, and hold as their identity. “I wonder what my identity is as a contemporary Indian puppeteer,” says Roy, as she reminisces over the influences that have shaped her work. “I encountered traditional forms of Indian puppetry very late in life. This was partly because of the lack of access to these forms, and partly because of my urban upbringing.”

She, however, adds that going to another country to learn puppetry was really not out of choice. “People like Dadi, Ranjana, me… we are all trained in Europe. But that’s because of the lack of formal training options within India,” she says. “And now, there is a whole lot of unlearning to be done, because there is a vital need to connect with the continuity of the tradition within India.”

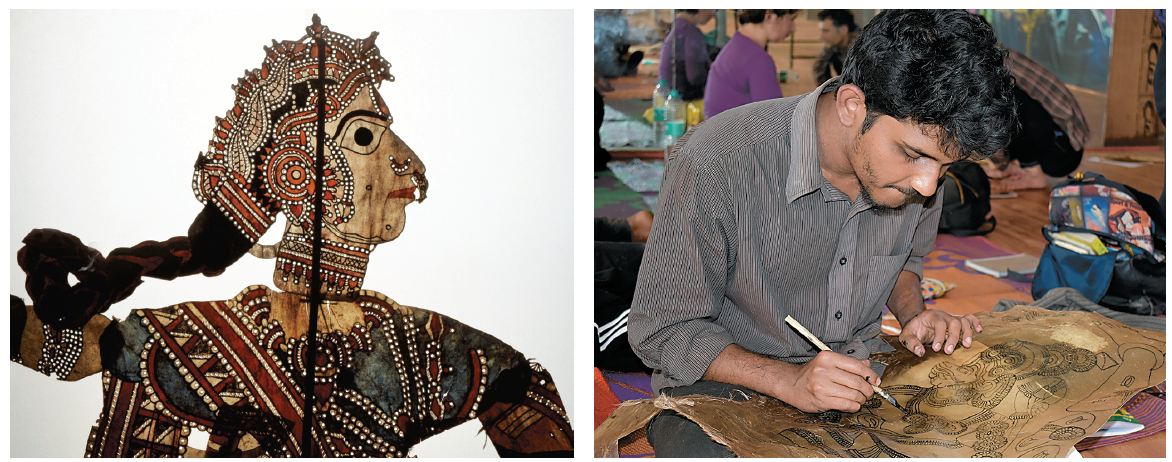

Trying to bridge the divide between traditional and contemporary forms, as well as present a platform for mutual sharing and learning is the Unima India Foundation Course for Puppeteers, which saw its first batch complete training in end-January. Roy’s Katkatha Puppets Art Trust, in collaboration with Unima India, started offering workshops in 2014. “We started with two-week Puppet Master Classes, with the first one being conducted in Mussoorie by master puppeteer Shri Gunduraju from the togalu gombayetta form of shadow puppetry from Karnataka,” says Roy. “It was a residential workshop that focussed on training in making and manipulating leather puppets, and traditional narratives.” (Left) A puppet from Karnataka's togalu gombayetta form of shadow puppetry (right) a student sketches out a shadow puppet at the Unima India Foundation Course, which includes a gurukul-style training at the home of shadow puppeteers

(Left) A puppet from Karnataka's togalu gombayetta form of shadow puppetry (right) a student sketches out a shadow puppet at the Unima India Foundation Course, which includes a gurukul-style training at the home of shadow puppeteers

Image: (Top Left) Werner Forman/ Universal images group/ Getty imagesAs a fleshing out of these workshops, Katkatha and Unima’s foundation course spans four months, with the first batch of students comprising traditional puppeteers, theatre artistes, and semi-practising puppeteers. The course includes classroom teachings on sculptures, puppet-making, story building, manipulation techniques and voice training it also includes a three-week gurukul-style training at the home of shadow puppeteers. Roy says they plan to organise such foundation courses every alternate year, with the 2020 one being a better version of the 2018 course.

“The impact that global influences have had on our puppetry is something we are asking ourselves all the time, and it has been a key consideration while formulating the foundation course,” says Roy. “While structuring the initial workshops, replicating a Western model was an option. But we have a 3,000-year-old tradition. No other part of the world, apart from Southeast Asia, has had continuous traditional forms such as ours. If we don’t incorporate these, we will be left rootless.”

First Published: Feb 23, 2019, 06:17

Subscribe Now