What PT Usha, Prakash Padukone and Milkha Singh have in common

Ahead of the upcoming film 83, on India's first cricket World Cup victory, here's a look at how a handful of Indian sportspeople overcame every odd to emerge world-beaters

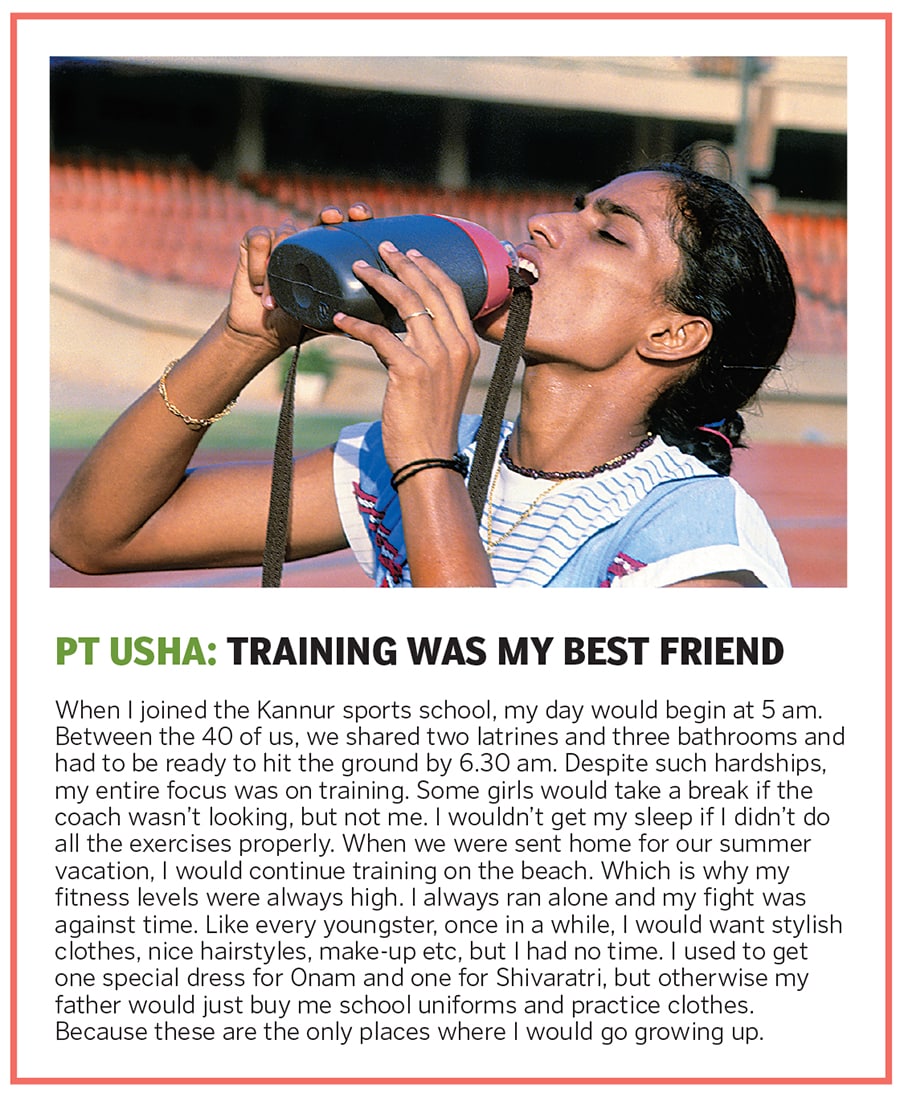

India"s foremost woman sprinter PT Usha, who missed an Olympic medal by one-hundreth of a second, at the Los Angeles edition of the Games in 1984

Photo: JUNJI KUROKAWA/AFP via Getty Images[br]In 1975, at a camp for under-22 cricketers in Mumbai, Kapil Dev and his teammates were served two chapatis and a spoonful of vegetables at the end of a sapping practice session. As he grumbled about the stingy portions, Dev was asked to take up the matter with administrator Keki Tarapore. “Sir, nobody can fill his belly with such a small serving. And I am a fast bowler,” 16-year-old Dev had told Tarapore, who had played a solitary Test for India. “Young man,” Tarapore had replied in jest, “India has been playing international cricket for over 40 years... it hasn’t produced a single fast bowler. Fast bowler? That’s the best joke I’ve heard in ages.”Three years later, Dev recalls in his autobiography Straight From The Heart, he made his Test debut against Pakistan, where he rattled a much-vaunted batting lineup with his searing pace, despite meagre returns in wickets. In the 52 Tests he played between July 1979 and December 1983, Dev picked up 17 five-fors. Considered an aberration in a country that famously nurtures its spinners, Dev has been credited by West Indian pacer Ian Bishop for laying the foundation for a future generation of pacers. Image: Dinodia Photo Besides his pace-bowling exploits, Dev’s moment of glory came on June 25, 1983, when he lifted the World Cup at the hallowed Lord’s Cricket Ground in London, which his team had won after defeating the mighty West Indies. India were considered minnows before the start of the event in which even the team didn’t grant itself a fighting chance opener K Srikkanth had made mere stopover plans in the UK, where the tournament was being held, en route to the US for his honeymoon. But the Haryana Hurricane, as 24-year-old Dev was nicknamed, held the entire cricketing world in thrall as he steered the team with his inspiring leadership, and a heroic innings of 175 in the win against Zimbabwe, having walked in to bat with the scorecard looking hopeless at four wickets for just nine runs. “That [World Cup] win inspired a lot of kids to take to the game,” Rahul Dravid, among India’s tallest batsmen in the following generation and former India captain, had said in an interview.

Image: Dinodia Photo Besides his pace-bowling exploits, Dev’s moment of glory came on June 25, 1983, when he lifted the World Cup at the hallowed Lord’s Cricket Ground in London, which his team had won after defeating the mighty West Indies. India were considered minnows before the start of the event in which even the team didn’t grant itself a fighting chance opener K Srikkanth had made mere stopover plans in the UK, where the tournament was being held, en route to the US for his honeymoon. But the Haryana Hurricane, as 24-year-old Dev was nicknamed, held the entire cricketing world in thrall as he steered the team with his inspiring leadership, and a heroic innings of 175 in the win against Zimbabwe, having walked in to bat with the scorecard looking hopeless at four wickets for just nine runs. “That [World Cup] win inspired a lot of kids to take to the game,” Rahul Dravid, among India’s tallest batsmen in the following generation and former India captain, had said in an interview.

Dev, who had never watched a Test match before playing in one, essayed an incredible turnaround for India with the World Cup victory, catapulting the country onto the global stage and stirring it awake from the proverbial dogmatic slumber. The significance of his role, being brought alive on the silver screen in the upcoming Hindi film 83, isn’t a mere statistic in sporting history but a testament to the virtues of human obduracy, of refusing to cow down in the face of adversity.

It’s a leitmotif that shapes the career trajectory of a handful of India’s earliest sporting heroes. Imagine the decades following Independence where the country’s socioeconomic edifice was still a work in progress, or the torpor of the 1970s and ’80s, before liberalisation opened up the economy in 1991. Those sluggish years set the backdrop for a set of disruptors to pursue sporting excellence with a frenzy.

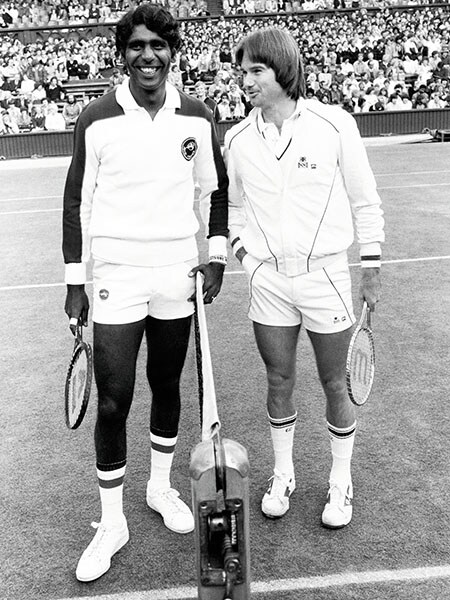

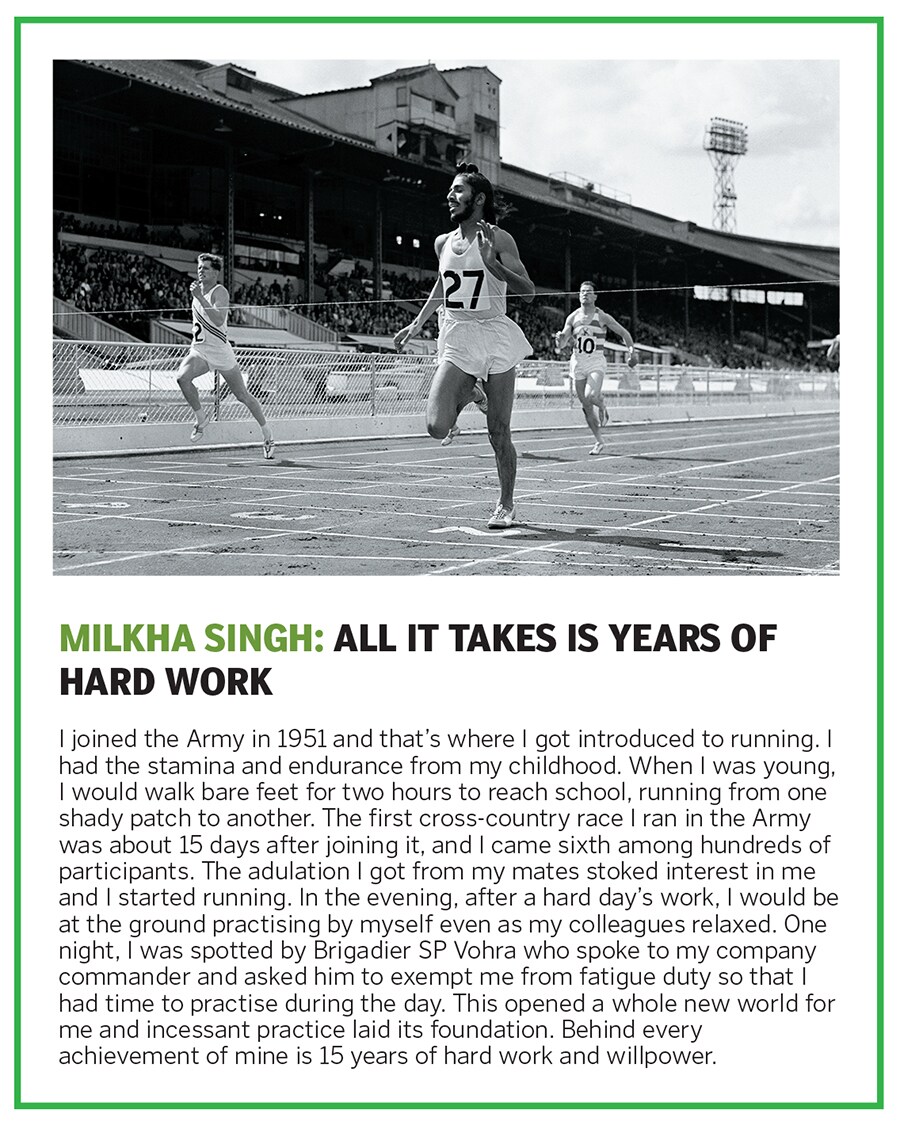

At a time when most Indians who could afford a car had to be waitlisted for several years to receive one, athlete Milkha Singh, orphaned during the Partition violence of 1947, brought home gold medals from the 1958 Asian and Commonwealth Games and came agonisingly close to an Olympic medal, missing out by a mere one-tenth of a second, at the 1960 Games in Rome. With no role models or templates preceding them, sportspeople like Singh displayed exemplary spunk and perseverance to achieve goals that would perhaps feel like pipedreams in the milieu they grew up in. Image: Jagdish Agarwal / Dinodia PhotoFor Vijay Amritraj, India’s highest-ranked professional singles tennis player, London, the home of Wimbledon and of his greatest exploits, had been a mere speck on the map. And for his peers, playing sport for money, which Amritraj aimed to do, was something unheard of. “No one had done it before me. I was flying blind. All of Chennai, where I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, thought I was nuts to pursue something that didn’t exist. ‘Yes you play tennis, but what do you do for a living?’ most people would ask me,” says Amritraj, considered the ‘A’ in the ABC of tennis, along with legends [Bjorn] Borg and [Jimmy] Connors. It was the conviction of his parents, who initiated the asthma-ridden child into the sport, and the resolve of his coach TA Rana, who read books, watched old films or news division at movies (where they showed clips of great players on fuzzy screens) that kickstarted Amritraj’s journey. “Mr Rana vowed to make me the No 1 in India before he died. And he did,” says Amritraj.

Image: Jagdish Agarwal / Dinodia PhotoFor Vijay Amritraj, India’s highest-ranked professional singles tennis player, London, the home of Wimbledon and of his greatest exploits, had been a mere speck on the map. And for his peers, playing sport for money, which Amritraj aimed to do, was something unheard of. “No one had done it before me. I was flying blind. All of Chennai, where I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, thought I was nuts to pursue something that didn’t exist. ‘Yes you play tennis, but what do you do for a living?’ most people would ask me,” says Amritraj, considered the ‘A’ in the ABC of tennis, along with legends [Bjorn] Borg and [Jimmy] Connors. It was the conviction of his parents, who initiated the asthma-ridden child into the sport, and the resolve of his coach TA Rana, who read books, watched old films or news division at movies (where they showed clips of great players on fuzzy screens) that kickstarted Amritraj’s journey. “Mr Rana vowed to make me the No 1 in India before he died. And he did,” says Amritraj.

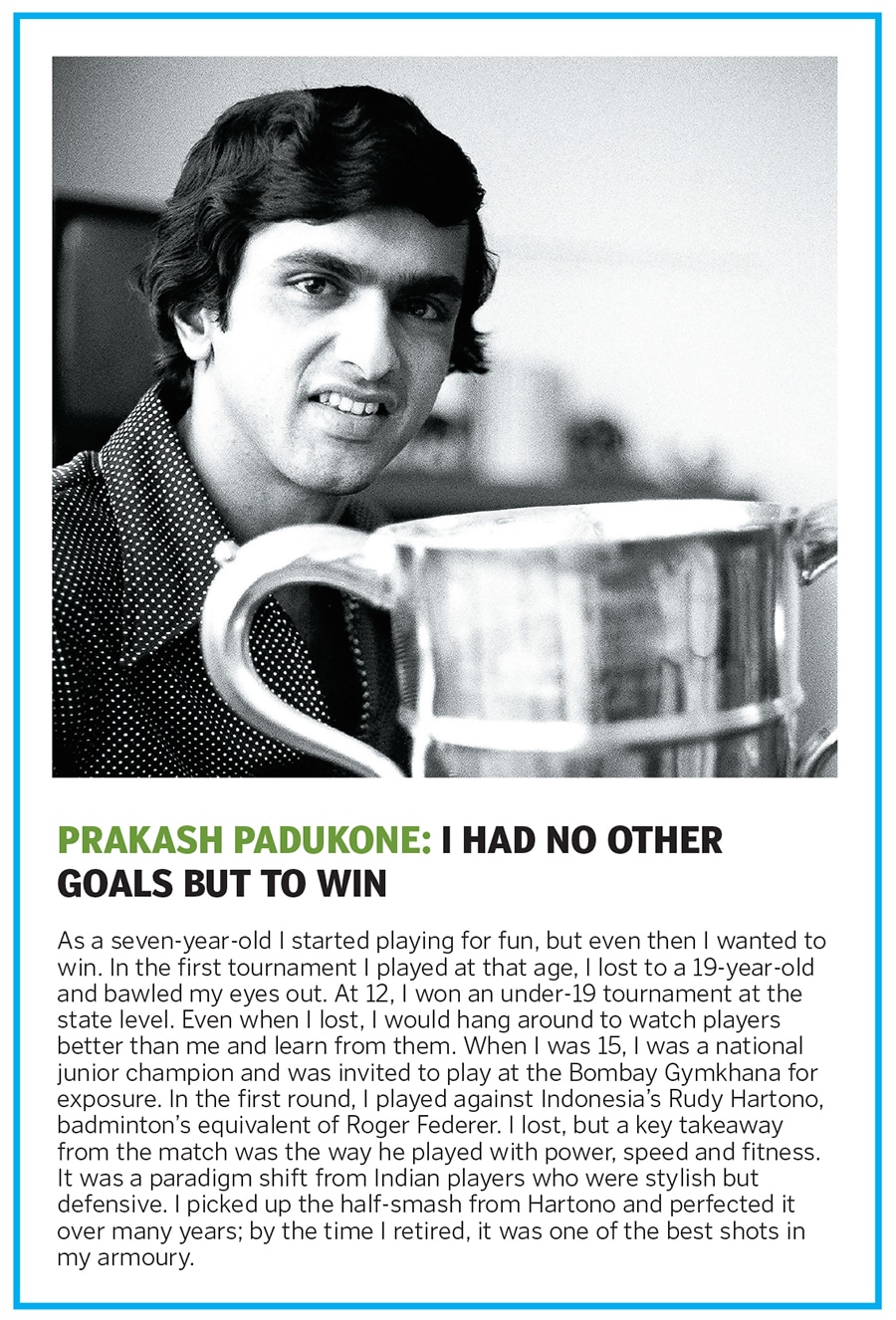

But starting up, to create something from nothing, isn’t easy. Many years before he became the first Indian to win the All-England Open Badminton Championship in 1980, the world’s most prestigious badminton tournament, a seven-year-old Prakash Padukone would check on a wedding hall in Bengaluru’s Malleshwaram neighbourhood every day on his way back from school. “If there wasn’t a wedding scheduled that day, I’d rush back home, pick up my racquet and return to play there. It would be difficult to get a day during the peak wedding season,” he recalls. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, Bengaluru had three badminton courts, which later went up to five. One among them was dictated by the wedding season and the whims and fancies of older players, who would limit on-court time for youngsters like Padukone.

The path less taken is also often peppered with detractors, as PT Usha, India’s foremost woman athlete to date, found out. A sickly child, her parents took her for the selection trials of Kerala government’s new sports training division in 1976. Usha, who lost out on a medal in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics by one-hundredth of a second, aced the two-tier trials and was selected for training in Kannur, about an hour and a half from her hometown of Payyoli. “My neighbours discouraged my mother from sending a girl away from home. Later too, when I would train with [Dronacharya awardee] coach OM Nambiar and would travel on his bike, people questioned my mother’s decision to allow her daughter to ride on a bike with a man. But my parents didn’t pay any heed to them,”says Usha.  Viswanathan Anand became India’s first chess grandmaster after his class 12 exam. His mother Sushila inspired him to take up the game

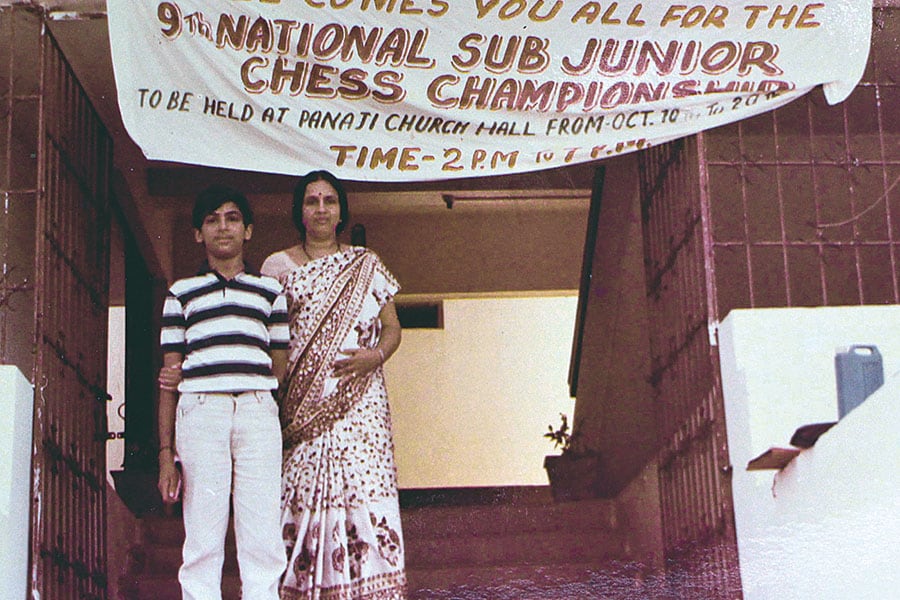

Viswanathan Anand became India’s first chess grandmaster after his class 12 exam. His mother Sushila inspired him to take up the game

Image: Personal archives of Viswanathan AnandBut, with success, the tide turns quickly. It silences adversaries and critics, and even resolves the academics-versus-sport conundrum that most middle-class families in India are confronted with. Padukone became a national champion at 16, Amritraj played the Davis Cup at 15, and Viswanathan Anand became India’s first chess grandmaster a few months after he cleared his class 12 exam. “By then, I was already a national champion for two months running. I was No 5 in the world by the time I finished my bachelor’s degree in commerce. The breaks came at a time when I would have had to make crucial decisions,” says Anand.

The year Anand became grandmaster, in 1988, was also the first year he got to practice on a computer, now a must-have in every player’s arsenal. “Computers were non-existent till I became a grandmaster. Books were the only source of chess knowledge,” says Anand. Which means his world-beating feat came from reading seminal chess literature like Chess Openings: Theory and Practice by Israel Albert Horowitz, which his sister bought for him from a local bookstore, or José Raúl Capablanca’s Chess Fundamentals and a few others. Anand received a computer as a gift in 1987 in Amsterdam, but had to leave it behind for about eight months till he secured government permissions to bring it into the country. Later that year, a laptop he bought was stuck with the customs department at the Chennai airport till the 250 percent import duty was waived off by the authorities after much persuasion.

The post-Independence decades also saw severe restrictions on foreign travel and foreign currency, under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act of 1973. “In the 1960s and ’70s,” says Amritraj, “you could leave India with only £3 [$8] per day per ticket. We had to win a match in the afternoon to be able to eat dinner.”

Padukone, who played his first All-England in 1973, couldn’t play the tournament for the next three years—in 1974 and 1976 for national policies, and in 1975 for funds shortage. “I was selected to represent India, but the association couldn’t sponsor me. It was out of question for my family and me to pay for a foreign trip and I dropped out,” he says. On many occasions, he adds, in the lead-up to his departure to a foreign tournament, he would have to travel from Bengaluru to Delhi to collect clearances from the government, pick up foreign exchange from designated banks, and head straight to the airport. Often, government clearances would not come on time. “We would have to come back to Bengaluru after going all the way. But we never complained, and started practising the next day. The situation inspired us to work extra hard. Since opportunities were rare, we tried to make the best of them.” Shooter Abhinav Bindra won India’s first ever individual Olympic gold at the 2008 Beijing Games

Shooter Abhinav Bindra won India’s first ever individual Olympic gold at the 2008 Beijing Games

Image: AFP Via Getty Images

Inventor Thomas Edison had famously defined the origin of genius as 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration. It’s a playbook that was adopted by India’s elite sportspersons as well.

Seated on the lawns of his Chandigarh home, Milkha Singh, now 91, recounts the story of his friend Dhyan Chand. “A multiple Olympic gold-medallist, Chand once told me how he scored so easily. Every day, he would tie a tyre to a goal post and practise hitting 500 balls through it. That made it very easy for him to find the target during the matches,” says Singh. “It’s the same with me. I practised like there’s no tomorrow, and often I would vomit blood and had to be put on oxygen.”

The Indian hockey legend had managed to impress even German dictator Adolf Hitler with his dribbling skills. Moved by Chand’s game during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Hitler offered him a position in the German army despite his team’s massive loss to the Indians in the final. Even cricketing great Sir Donald Bradman had once equated Chand’s ability to find the net with the ease with which one scores runs in cricket.

Like Chand came up with his own tricks to improve his game, so did Usha. Through the ’70s, during her formative years in Kannur, Usha didn’t have so much as a gym for weight training. She would tie a towel to either end of a window, prop her leg up on it and rested her head on a bench below to imitate an incline bench for her abdomen exercises. And even when most of her peers were done, or took a break behind the coach’s back, she kept going.

It’s this gnawing urge to excel that consumed Abhinav Bindra, India’s first individual Olympic gold medallist, and spurred him to leave his comfort zone in Chandigarh at 15 to head to the German town of Wiesbaden to join a shooting academy. Or, some years later, to ditch his plush home in favour of a small room with a bunk bed at an air force barracks-turned-training facility in Colorado Springs, US, where he got to train with and learn from US Olympic athletes. Later, in preparation for the Beijing Olympics in 2008, where he finished on top in 10 mt air rifle, Bindra converted a wedding hall in his hometown into a shooting range to simulate the gigantic arena in which the Olympic final was held. “Such large spaces overwhelm a shooter and upset their balance. That’s why I had to prepare,” says Bindra, adding with a chuckle, “That’s also probably the closest I’ve come to marriage.”

A liberalised economy, and an affluent family allowed Bindra to overcome administrative hurdles and take up foreign jaunts with relative ease. But Padukone, who had self-trained all his life, barring a few fundamental lessons from his father, found himself at a crossroads at 25, when he was national champion for the ninth consecutive year, but hadn’t done anything of note at the international level. One day, the managing director of Union Bank, where he was employed, asked what it would take for Padukone to elevate his game by a few further notches. “Maybe train with the national team of Indonesia, then a badminton powerhouse, I replied. The company agreed to sponsor a six-week stint for me, something unheard of in those days,” he says.

Padukone and Syed Modi, then the No 2, landed in Jakarta in 1977 without even a place to stay. A few Punjabi families who owned sports goods shops in the country had come to receive them at the airport and housed them at a local gurdwara. “Both Syed and I slept on the floor, had meals at the langar and rode 25 km each way to the training venue on a scooter every day, twice a day. But the training sessions were an eye-opener,” says Padukone. Vijay Amritraj is considered the ‘A’ in the ABC of tennis, along with legends Bjorn Borg and Jimmy Connors

Vijay Amritraj is considered the ‘A’ in the ABC of tennis, along with legends Bjorn Borg and Jimmy Connors

Image: Art Seitz / Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesPadukone probably was the fittest shuttler in India, but once he started working out with Indonesia’s national team, he realised how limited his efforts were. For instance, he had no idea that a cardio routine had to be complemented with weight training. “I wrote down everything in detail—each exercise, number of sets, the number of minutes, the sequence—and started following them in toto. The results showed immediately. In the early days, I was losing practice games to 3 and 5 points. By the end of the six weeks, I started beating some of them,” says Padukone. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the very next year Padukone won the singles gold in the Commonwealth Games and two years later the All-England title, beating Indonesian Liem Swie King in straight games. “I hear Indonesia stopped such exchange programmes since,” he laughs.

What Padukone learnt in Indonesia, Milkha Singh learnt the hard way through his first-round loss in the 400 mt event of the 1956 Olympics. After the race, Singh, who barely had any conversational skills in English back then, landed up at the door of Charles Jenkins, the gold medal-winner in his discipline and a neighbour in the Games village in Melbourne, and asked him in gestures if he would coach him. “400 mt coaching to do, was all that I could put together,” says Singh, who was asked to meet Jenkins the next day. When he returned, Jenkins broke down his training schedule for the year—the quantum of hill running and sand running that he did to raise his stamina, the number of starts he would practice every day etc. “From the day I returned from Melbourne, I would follow that routine every single day.”

Besides his assiduous training, Singh also attributes his success to the doggedness of his coaches—Ranvir Singh and Havaldar Gurdev Singh of the Indian Army, where he was deployed since 1951. Coach Ranvir would shadow Singh “like it was nobody’s business”, following him on a cycle as he would go for a run on the hill and instructing him as he would build up his leg muscles by running on the sand. “Even if my girlfriends would come to talk to me, he would sit through the conversation and ask me to come for training once done,” says Singh. The invectives that Gurdev would shower on them during their practice with the army—“Haramzadon bhaago [run, you bastards]”—would often propel Singh to put in that extra yard or two. Image: S&G / PA Images via Getty ImagesLike Singh, most athletes have behind them a legion of unsung cheerleaders, whose lives are subsumed by the motto of helping them perform better. For Anand, it was his mother Sushila, also his first sparring partner and whose keen interest in chess prodded Anand to take it up. In the ’70s, Anand’s father was posted in the Philippines, also the home of Eugenio Torre, Asia’s first grandmaster. In a country that had already shaped up as a chess-playing hub in the continent, Sushila not only got him admitted to a club for training, but spent her afternoons watching chess shows, noting down puzzles and getting Anand to solve them once he returned from school.

Image: S&G / PA Images via Getty ImagesLike Singh, most athletes have behind them a legion of unsung cheerleaders, whose lives are subsumed by the motto of helping them perform better. For Anand, it was his mother Sushila, also his first sparring partner and whose keen interest in chess prodded Anand to take it up. In the ’70s, Anand’s father was posted in the Philippines, also the home of Eugenio Torre, Asia’s first grandmaster. In a country that had already shaped up as a chess-playing hub in the continent, Sushila not only got him admitted to a club for training, but spent her afternoons watching chess shows, noting down puzzles and getting Anand to solve them once he returned from school.

What emanates from such unflinching love and support is self-affirming confidence that helps athletes fight the demons in their heads in difficult times and through tough losses. Bindra’s world came tumbling down after finishing seventh at the 2004 Athens Olympics despite doing well in the qualification rounds. “A few minutes after the final, I met my mother and she told me today you could have gone on to win a bronze or a silver at the most. But you are going to win a gold medal someday. Imagine, I am heartbroken and my mother is still convinced that I’ll win the gold,” says Bindra.

Once such prophetic convictions come true—for Bindra it was at the next Olympics in Beijing—the grit and grind seem worth it. For India’s game changers, who flipped the switch for the country on the global stage, it’s not merely a moment of self-aggrandisement, but also one of opening the doors for the next generation to follow. When Anand started playing chess, India didn’t have a single grandmaster, now there are 65. Padukone’s journey at the All-England has been emulated by

P Gopichand in 2001, who subsequently steered his wards Saina Nehwal and PV Sindhu to Olympic medals and World Championship titles. This year’s Olympics in Tokyo will see India send one of its strongest shooting contingents, with a number of medal hopefuls looking to repeat Bindra’s feat.

Amritraj has a prescription for all such aspiring world-beaters. “On the wall of my house, I’ve pasted a great saying by [American poet] HW Longfellow. It goes, ‘The heights by great men reached and kept were not attained by sudden flight, but they, while their companions slept, were toiling upward in the night’.” India’s pioneering batch would concur.

(Additional reporting by Divya J Shekhar)

First Published: Mar 14, 2020, 06:18

Subscribe Now