The pandemic conversations that leaders need to have now

It's time for leaders to rebuild the bonds that COVID-19 has shaken. First step: Start talking. Boris Groysberg and colleagues share advice for making these conversations meaningful.

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

When our team reached out to 600 CEOs during the pandemic’s early stages to ask them about their greatest concerns, many cited communication with employees.

While the right communication strategy has been critical during the pandemic, it will remain just as critical—if not more so—when we transition back to “normal" (whatever that means). Although we are still living in COVID-19’s grip, companies are starting to devise plans to bring their workforces back to the office in the coming weeks and months.

In recent conversations with CEOs and other company leaders, people have shared mostly top-down, generic approaches to communicating their plans with their employees. Although mass emails and newsletters are not problematic in and of themselves, they are no substitute for the kind of communication this moment calls for—namely, conversations. In fact, leaders should start scheduling frequent conversations with individual employees during this critical time.

Conversations are the best way to get leaders and employees back into the practice of relating to one another in person. How are people doing? What challenges are they facing at work and in their personal lives?

It’s essential that leaders manage these conversations effectively. Drawing on our insights and those of others, we offer this guide to help leaders have the kinds of discussions we need to be having right now.

The four I’s of conversational leadership

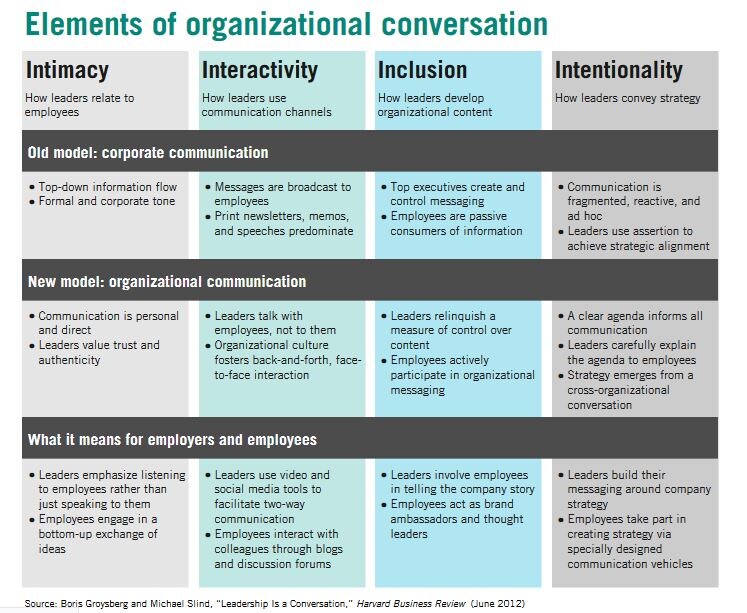

The book Talk, Inc.: How Trusted Leaders Use Conversation to Power Their Organizations, by Boris Groysberg and Michael Slind, explores how companies’ outreach strategies evolved from top-down, command-centric communiques to something more informal, immediate, and personal—from a C-suite monologue to a genuine back-and-forth between leaders and employees. This change has driven:

• The rise of knowledge work

• Trends toward flatter, less hierarchical organizations and recognition of the value-creation of frontline workers

• Increasing diversity and globalization, creating an awareness of different communication styles and cross-cultural competencies

• The growth of social media and instantaneous communication

• Generational change as millennial and Gen Z workers with a more egalitarian, self-expressive style move into the workforce (and, at this point, into leadership roles: the oldest millennials are nearing 40)

All of these trends have only accelerated since the book was published in 2012. When you add in the unprecedented communication requirements of the pandemic and the subsequent transition back to the workplace, conversational leadership becomes a necessity.

The book provides a framework for conversational leadership based on four principles—intimacy, interactivity, inclusion, and intentionality—that reinforce one another.

Intimacy

Leaders must be honest and vulnerable with their teams, presenting themselves as fully human and recognizing their employees’ humanity as well. Intimacy means closeness, and while social distancing remains important to mitigating the spread of COVID-19, psychological proximity—interpersonal trust, alignment on values and strategy, shared understanding of key facts—has never been more crucial. Psychological proximity requires gaining trust, listening well, and getting personal.

Principles and practices:

Acknowledge the facts. If you aren’t the most reliable source of information, your employees are going to try to find a better one. Be honest and transparent about the situation and its implications, including what is known and unknown at the time, and the timeline for decisions. Employees understand that events are continually unfolding and will accept changes if the evidence and reasoning are clear. Boilerplate rhetoric will likely disengage them.

INSEAD’s Jennifer Petriglieri studied BP’s handling of its oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and observed how top talent reacted differently to the crisis based on the messages they received:

“Some lost faith in the company and in its leaders. Others doubled their effort and commitment. The difference between the two groups? The former was exposed to the top brass’ upbeat messages. The latter had bosses who drafted them to help clean up the mess. Despite the stress, working closely with one’s boss and colleagues on the response was more containing and informative. It reassured those who did it about the company’s integrity and long-term viability."

This work also shows the importance of local leadership: An individual manager can be an authentic communicator even if their organization is not.

Jennifer Petriglieri’s colleague and husband, Gianpiero Petriglieri, recommends that leaders “tell your people what will happen to their salaries, health insurance, and working conditions. What will change about how they do their work? What are the key priorities now? Who needs to do what? You might not be able to make predictions, but you can still offer informed interpretations, that is, why certain measures are sensible and needed instead of others. Dispel rumors."

"Acknowledge the uncertainties of the future and the strains of the present."

Acknowledge the feelings. When sharing difficult news—or even beginning an ordinary staff meeting, some days—acknowledge the uncertainties of the future and the strains of the present. Likewise, when team members share their losses and challenges, acknowledge their pain before addressing the substance of the problem. This does not have to be a deeply emotional moment to be sincere: The script can be as simple as “I’m so sorry that must be awful for you. I appreciate your bringing it to me."

Author and CEO Peter Bregman advises leaders to “just start with the relationship—even if you don’t feel like you have an established one—because showing care and concern is what creates that relationship. What’s so powerful about empathizing first is that it affects both the receiver (me) and the giver (my supervisor). When we express our care and concern, we’re far more likely to feel our care and concern."

One CEO told us that empathy is “always an important leadership skill, but this empathy is dramatically heightened during a crisis that is impacting everyone personally and professionally. Keeping in mind the person on the other end of a call may be having a dramatic experience during this crisis is an important subtext for how they are navigating the conversation with me."

Acknowledging that people are having a hard time whether or not they are showing it, and letting them know where to get help, is an important part of a leader’s job right now. Remember: People can manage their feelings if you give them the facts. And they can manage the facts if you acknowledge their feelings.

Leaders go first. It’s on leaders to make the first move to close the distance by speaking honestly, simply, and clearly about matters at hand, and demonstrating their willingness to listen. Leadership experts Frances Frei, the UPS Foundation Professor of Service Management at HBS, and Anne Morriss note that trust has three factors: authenticity, logic, and empathy.

“People tend to trust you when they believe they are interacting with the real you (authenticity), when they have faith in your judgment and competence (logic), and when they feel that you care about them (empathy)," they write. Put together, these factors argue for an informal, straightforward communication style.

Employees get the news first. Nothing erodes trust for employees like learning job-relevant information from the news or social media. Think about ways to increase transparency. One leader we talked to said their company hosts quarterly conference calls that employees can listen to:

“The first half is top executives’ discussion of the quarter and expectations. The second half they have a roundtable-like discussion on a particular topic about specific customer sectors. They want to show employees how they work in those areas."

Some organizations live-blog or live-tweet their corporate meetings or events to give employees a sense of the back-and-forth in the moment. The virtual platforms that companies are relying on these days offer a similar opportunity to invite audiences to leadership meetings.

Interactivity

Intimacy creates a more genuine style of leadership communication. Interactivity turns that communication into a two-way dialogue, allowing management to respond to workers’ needs better, and act on their insights. Technology can facilitate a feedback process, but it cannot create a feedback culture. Even during the heyday of the suggestion box, some overflowed with penciled index cards while others sported cobwebs.

Dialogue is necessary for creating a shared reality—especially now. People’s pandemic experiences have varied widely depending on pre-existing factors of location, gender, family configuration, living situation, age, marital status, and more. Every one of your team members has a unique perspective on the past year. Have individual conversations to find out what people need and what insights they might have.

Principles and practices:

Check your culture. Is your organization a psychologically safe one? Do lower-level team members feel respected? Do people in your organization share or hoard knowledge? Is mutual aid and friendship the norm? Do people funnel feedback, news, and questions upward, or do they pacify and protect their bosses? What happens when people make mistakes?

If your organization doesn’t seem psychologically safe, create venues for honest questions and ideas. Find a channel for people who have concerns they may not want to bring to their direct supervisors. In meetings, allow people to submit anonymous questions to leaders. Asking “What questions do you have?" after a presentation is better than “Do you have any questions?"

Make sure people feel heard. Recapping other participants’ points before making your own is a helpful practice in all meetings, but especially virtual ones. This lets people know if they were heard correctly, and keeps the conversation connected rather than a series of disjointed monologues.

“Before you raise a new topic, reiterate what you just heard or the previous point you plan to riff on—even ask the speaker whether you’ve characterized their point correctly. Not only does this help the conversation, but it makes it more likely that others will hear what you have to say. People are more likely to listen if they first feel heard," according to communications expert Sarah Gershman.

Inclusion

The principle of inclusion expands employees’ roles beyond listening and responding to co-creating the company narrative and serving as brand ambassadors, thought leaders, and storytellers.

During a time of widespread unemployment and economic uncertainty, the people who have jobs are talking a lot about how their companies are handling the crisis and the transition to more normal business operations. Everyone wants to know who’s doing poorly and who’s doing well and why. Prepare your people to be brand ambassadors. If a customer isn’t comfortable going to the store yet, the help-desk person she’s chatting with becomes her only connection to the company’s values, narrative, and customer experience.

Korn Ferry’s leadership guide (pdf) notes that giving employees a voice is “good for the organization" because “leaders don’t need to have all the answers. The best ideas will often come from far-flung corners of the organization." It is similarly beneficial to employees: “To be engaged, employees must feel heard and understood. Moreover, they must see their thoughts and reactions come to life in the real world. This is an opportunity for new leaders and innovators to emerge."

Principles and practices:

Connect the dots. Tie conversations back to key organizational priorities. Help employees see how their work fits into the organization’s larger mission—and to their personal missions, as well. This has always been good organizational practice, but has become even more critical now. As Francesca Gino, the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration at HBS, and London Business School’s Dan Cable describe:

“Discuss with employees whether any of the basic elements of their work have changed or will change. Get them to prioritize whom they are trying to serve and what they need from you in order to be effective. This type of conversation can provide the clarity needed to personalize our work’s purpose better than an organization’s vision or mission statement, which is often so grand that employees have difficulty connecting it to their daily tasks."

In a similar vein, McKinsey & Co. advises that “While it’s important to shape a story of meaning for your organization, it’s equally important to create a space where others can do the same for themselves. Ask people what conclusions they are drawing from this crisis and listen deeply."

Foster mutual support. The transition back to the office may be a good time to dismantle silos and foster relationships across department, function, rank, and location. This is especially so at a time when so many people are dealing with similar practical challenges. Internal blogs, groups, or other forums can help employees in similar situations (e.g., working parents and eldercare providers) or those interested in similar topics (baking or jigsaw puzzles) share information, recipes, items for sale or barter, and the like.

Keep such forums tied to the organization’s identity and mission. The feeling should not be one of an anonymous Craigslist but one of teammates supporting each other through unprecedented times. The McKinsey guide recommends that leaders strive to “rebuild a common social identity and a sense of belonging based on shared values, norms, and habits. Research suggests that social bonds grow stronger during times of great uncertainty."

Foster community involvement. This can take two forms. One is for organizations themselves to join or create a community endeavor, and invite employees to participate. Many organizations sponsor United Way drives or do a volunteer day with Habitat for Humanity. Others have started their own initiatives, such as scholarship or internship competitions, coat drives, or clean-up days. Given the magnitude of need during this crisis, there are many ways an organization can give back and involve employees. By doing so, you will begin to incorporate the COVID-19 crisis into the larger organizational narrative.

The other way to foster community involvement is to empower employees to represent the organization to people in other parts of their lives. Managers should want their employees to have lives outside of work, not only because it’s better for employees’ health, but because that’s where customers live.

Enthusiastic employees are an organization’s best representatives, and they may have access to audiences and demographics that you cannot reach otherwise. Such in-house brand ambassadors have smaller followings than celebrities or professional influencers, but their advocacy is far cheaper, better informed, and more trustworthy than outreach from a representative less attached to the company.

Pay attention to, develop, and reward internal expertise. Such talent will naturally begin to surface as a result of the processes outlined here and the inherent disruption of the pandemic.

Intentionality

Intentionality keeps these intimate, interactive, and inclusive conversations tethered to organizational goals and challenges. Unlike social conversation, organizational conversations are teleological—directed toward a specific end. In this case, that end is the shared understanding of the facts on the ground, the plans going forward, and the rationale behind those plans.

In times of crisis, this function is—in a turn that should surprise no reader by now—more important than ever. Gianpiero Petriglieri borrows the concept of “holding" from psychology to explain how leaders not only set aspirational visions, but help their followers function in day-to-day reality. These leaders know how to restore calm and guide others through complex situations. Petriglieri writes:

“Think of a CEO who, in a severe downturn, reassures employees that the company has the resources to weather the storm and most jobs will be protected, helps them interpret revenue data, and gives clear directions about what must be done to service existing clients and develop new business. That executive is holding: They think clearly, offer reassurance, orient people, and help them stick together. That work is as important as inspiring others. In fact, it is a precondition for doing so."

Principles and practices:

Know why you’re communicating. For each communication “event," ask yourself: What are your goals? What effects do you want the communication to have? How will you know if the message has been received? How will you know if you are getting all the relevant information you need? What has and has not worked in your communication strategies thus far?

Draw a literal picture. Everyone is overwhelmed with text. Visual aids can be extraordinarily useful. Legendary Duke Energy CEO Jim Rogers, for example, distributed a one-page drawing to his staff to explain the complex competitive environment outside of the company.

Structure conversations. Set topics, agendas, and deliverables for meetings in advance, and share that structure with attendees. People should know how they should contribute, and when they can ask questions and offer feedback or ideas. After the meeting, summarize the discussion to make sure everyone was heard, and let participants know what will happen next.

Liana Kreamer and Steven G. Rogelberg, both of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, argue that many meetings should not end with a decision. They recommend several other options:

“If the meeting is relatively small in size (under six attendees), you could debrief with your team—hosting a verbal discussion of what emerged. If the meeting is larger in size, the meeting can end for now. You could then take time to go through the document and see what materialized. You could share general conclusions and next steps with the group in a follow-up email. Or, you might consider sending out a quick survey post-meeting where folks vote on final options for ways forward or share ratings of prioritization. Separating discussion and deliberation from actual decision making—as described here—has been found to promote better meeting decision quality."

Tie conversations to action. While deliverables may not emerge at the meeting, they should emerge from the meeting in a prompt and direct way. Remember the BP study and how involving employees directly in the crisis response influenced their commitment. Many organizations are trying to do the same with stakeholders during the pandemic.

Restarting relationships after a tough year

People have been through so much during the past year, and no one will be returning to work as the same person they were before the pandemic, leaders included. Relationships will need to be re-established, and people may be rusty after a year of Zoom interactions.

In November, we wrote about the importance of exhibiting kindness to employees during the pandemic, and the same principle holds true for the transition back to the workplace. Leaders should take this opportunity to practice kindness through conversations for the good of their employees and their organizations.

Boris Groysberg is the Richard P. Chapman Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. Robin Abrahams and Katherine Connolly Baden are research associates at HBS.

First Published: Apr 28, 2021, 12:51

Subscribe Now