How Gupshup turned into a profitable unicorn despite a pivot and two near-deaths

The company has emerged as a global leader in B2B conversational messaging and claims to have over a lakh developers and businesses as its clients

Beerud Sheth, co-founder and CEO, Gupshup (Image: Nadine Priestley)

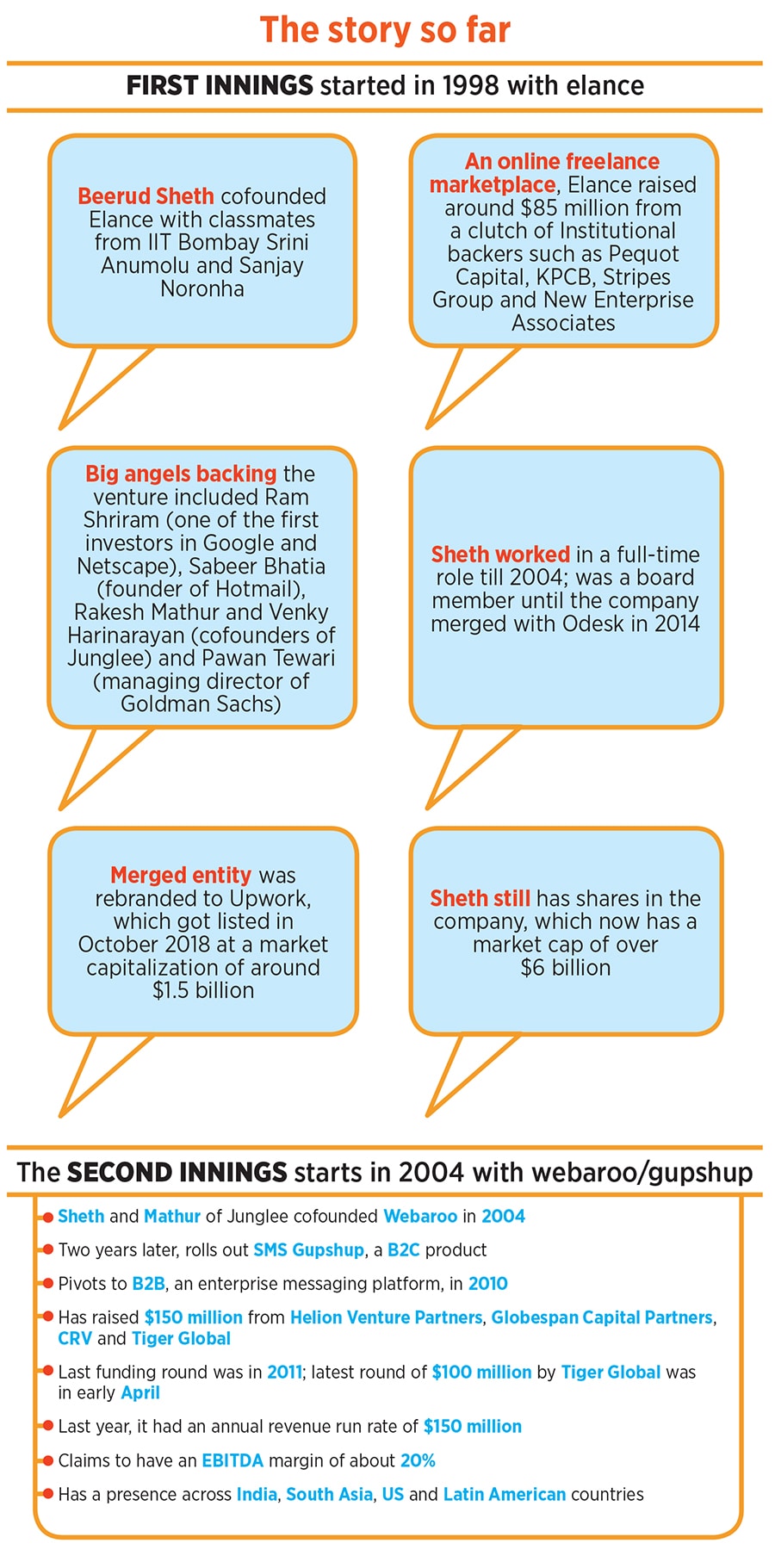

In 2010, Beerud Sheth found the going exhilarating. “Oh my God! Look at the growth," exclaimed the second-time entrepreneur towards the end of the year. The pace of the growth at SMS Gupshup—a Twitter-like community site that enabled users to join groups of their interests and get updates through SMS (short message service) on mobile—was astounding: 70 million users in over three years since its launch in April 2007. “It was the largest social network in India by a huge margin," claims Sheth, who managed to raise $10 million in 2008. The timing of the funding--barely a few days before a global financial meltdown—was perfect. Getting big backers on board such as Helion Venture Partners and Charles River Ventures at such a time was the initial thrill.

Then, in 2010, SMS Gupshup raised another $10 million. The bigger thrill this time around for Sheth and his cofounder Rakesh Mathur was that their baby had massively outpaced Facebook, which then reportedly had over 8 million users in India. Even when combined with Twitter, it was no match for SMS Gupshup. “When a person would send a message, SMS Gupshup would send it to all her followers—even if there were 10,000 of them," says Sheth, explaining how the network worked. The service was free and the company, he lets on, would pay the telecom operator for sending all messages. The focus, Sheth underlines, was on getting users. “A big community could be monetised later," Sheth believed. The hard part, he was convinced, was building a large pool of consumers. “SMS Gupshup was turning into an extremely successful product," he adds. A year later, the company managed to raise another $10 million.

The success, though, turned into a kiss of death. “OMG! Look at the growth. How will we pay for it," Sheth panicked in 2011. The hard part—building a big community—brought a harder problem. As the community bloated, so did the cost of subsidising all messages. The company was hemorrhaging because of two reasons. First, the cost of SMS—which Sheth presumed would decline as telecom operators started getting big volumes—didn’t come down. “We were sending billions of messages and spending crores of rupees every month," he rues. SMS Gupshup was fast running out of cash. Second, the monetisation plan could never play out. Reason: The company planned to put footer advertisements at the bottom of the messages but the regulations didn’t give Sheth such an option. “We could neither subsidise nor monetise." The company was gasping for breath. Though the VCs were ready to pump in some money, it was not sufficient. “Some of these problems take a lot more money. You cannot solve them with little money," he says.

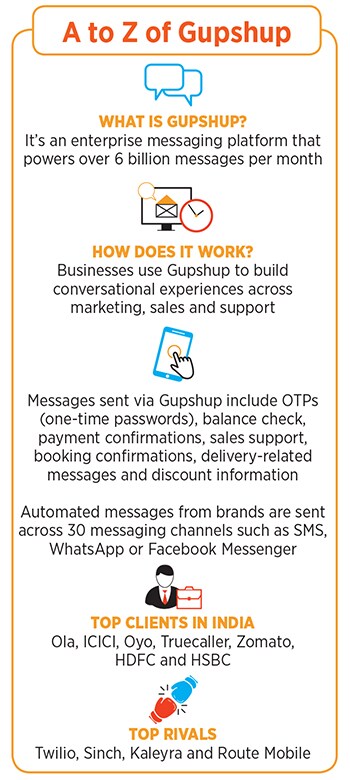

To avert an imminent death, SMS Gupshup made a B2B pivot. The name changed to Gupshup and the platform was now for enterprise messaging, which means that businesses could build conversational experiences across marketing, sales and support system and send messages to consumers such as OTPs (one-time passwords), balance checks, payment confirmations, sales support, booking confirmations, delivery-related messages and discount information.

Two years later, though, nothing much changed. Gupshup was again fast running out of cash in 2013. But this time, it was a catch-22 situation. Revenue failed to keep pace with expenses. The easy solution was to cut down expenses. But the moment they did that, growth took a hit. “We had to keep spending to bring in more revenue," explains Sheth. Cutting costs, he stresses, meant not focusing on infrastructure, which led to technical problems, and which, in return, meant annoying customers as the experience suffered. “To get out of this, we needed to spend more," he adds.

The second near-death experience, and that too within a span of two years, jolted Sheth to the core. What, though, hurt most was not the gruelling fight to survive but a crippling blow to the self-belief of an entrepreneur. “It’s funny when you go to school, and have a great academic career (and then this happens)," he quips. Sheth came first in the National Talent Search (a national scholarship programme at the secondary school level to identify students with high intellect and academic talent) he came third in the Indian Math Olympiad was a top ranker in the IIT entrance exam a silver medal winner at IIT and then came MIT. In exams, Sheth explains, if you get the highest scores, it means you have succeeded. “It makes you think that you can succeed at everything," he adds.

A founder’s life, though, was a different world. Entrepreneurship turned out to be a humbling lesson. Sheth was constantly failing and trying to work around the next failure and fix it. Elance, his first venture of online freelance marketplace started in 1998, too was well ahead of the time. “Some didn’t believe in my story then and the rest were sceptical," says Sheth, who worked in a full-time role in the company till 2004. A decade later, Elance merged with Odesk.

Fast forward to 2021. A decade after raising the last funding round, Gupshup has turned unicorn, a privately-held firm with a valuation of $1 billion and more. Early this month, the company raised $100 million from Tiger Global Management, propelling the company’s valuation to $1.4 billion. The company has emerged as a global leader in conversational messaging claims to have over a lakh developers and businesses as its clients and delivers over 6 billion messages per month across 30 messaging channels.

What is most gratifying for Sheth is not the prized unicorn tag which most of the entrepreneurs unfailingly flaunt, but the profitability docket. “Gupshup is profitable and doesn’t need money for survival," he says, claiming to have an EBITDA margin (profit margin before interest, tax, depreciation & amortization) of 20 percent. Most of the companies, he reckons, do a funding round because they have to, but Gupshup did it because it chose to. “I just happen to be a cockroach that turned into a unicorn," he smiles. (Cockroach startups are ones that focus on making money, aim at profitability and survive despite all odds.) Being profitable, Sheth contends, is a huge relief. As an entrepreneur, when you are on a short runway, you are always worried that the runway will come to an end. The latest funding, Sheth asserts, will be followed by additional funds raised from more investors.

Gupshup’s latest backer—hedge fund Tiger Global—is pleased with the way the venture has shaped up. “In addition to its market leadership, Gupshup’s unique combination of scale, growth and profitability attracted us," says John Curtius, partner at Tiger Global Management. The growth in business use of messaging and conversational experiences, transforming virtually every customer touchpoint, is an exciting secular trend. Gupshup, Curtius points out, is uniquely positioned to win in such a market with a differentiated product, a clear and sustainable moat, and an experienced team with a proven track record.

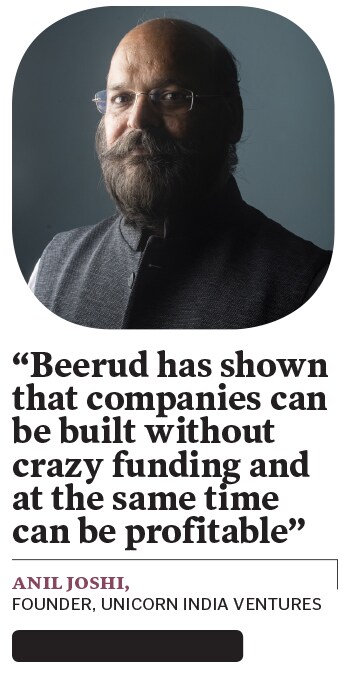

Gupshup, point out venture capitalists and industry experts, is a classic case of the ‘hare and tortoise’ story. The company started like a hare, ran on rocket fuel and was much ahead of its time. “Regulatory restrictions made them pivot, and forced them to walk like a tortoise," says Anil Joshi, founder at Unicorn India Ventures. The good part of a tortoise walk, Joshi explains, was that Gupshup steadily kept walking, ignoring the noise around them, and built a solid company. “Beerud didn’t give up. He slowly worked his way out and showed that companies can be built without crazy funding," he says. In fact, he is behind two unicorns. The first company, which got merged in 2014 and rebranded as Upwork, got listed on Nasdaq in October 2018 at a market capitalisation of around $1.5 billion. “He is truly an inspiration for many," says Joshi.

Sheth, for his part, found inspiration in the serenity prayer, where a person asks for three things from God: the courage to change things she can the patience to accept the things she can’t, and the wisdom to know the difference between the two. “This has been my first guiding principle," he says. The second one, he points out, revolves around the cardinal message of Bhagavad Gita: stay focussed and not get distracted. “Once you have a clear vision and conviction, then everything else is just noise." One just needs to focus on what can help to move ahead in life, and ignore anything else that distracts one from that goal, he adds.

Sheth might have joined the unicorn club, but his handling of the tag is guided by heavy dose of spiritual philosophy and realism. In tech companies, he stresses, one needs to remember that valuations can go up and as well as come down, and at times the dip can be as sharp as 90 percent. “Many unicorns will not remain unicorns," he says. When companies die, they die quietly, and when they succeed, there is a lot of media and buzz around it. In India, Sheth underlines, the birth of a flurry of unicorns might be a new phenomenon, but in Silicon Valley, there have 50 years of unicorns. “It’s a good milestone but not an achievement," he says, pointing out one big upside of achieving unicorn status. “It helps in growing business as you start getting a lot of attention, especially from customers, partners, and potential employees you want to hire."

For entrepreneurs, though, only one thing should grab their attention: the slog, fixing problems, and staying balanced. One doesn’t need to get carried away when things are great, and one must not get depressed when things are bad. “Just like failure may not be my fault at times, success too may not be my credit," he says, dishing out a piece of advice for budding entrepreneurs. “Keep building value. Valuation will follow."

First Published: Apr 28, 2021, 12:58

Subscribe Now