Epharmacies: Click to heal

The market for epharmacies is substantial but evolving a profitable business model will take time

Rahul Parekh founded online pharmacy RxHeal in 2015 he aims to become a thought leader in the generics space

Rahul Parekh founded online pharmacy RxHeal in 2015 he aims to become a thought leader in the generics space

Over the past two decades, Rahul Parekh has been on the go. The 47-year-old was KPMG’s first employee in India in 1994, launched his own consultancy and helped acquire and consolidate a gaming business for an Italian family. Then, in 2015, Parekh saw an opportunity in the pharmacy space. At ₹100,000 crore, according to AIOCD, an Indian pharma market research company, this was a market fragmented among 800,000 chemists across the country. Surely, with the use of technology, the unit economics of the business could be improved. It was and is a sector ripe for consolidation, Parekh believed.

He is not alone. At least a dozen epharmacies have staked their claim to this market. As sales of branded generics have risen steadily in the last decade, the Indian pharma industry is closely monitoring the growth of this new sales channel. Yet most buyers who’ve done away with their neighbourhood pharmacist and opted to shop for their quota of medicines online will find it hard to admit that they weren’t (at least initially) tempted by the discounted prices.

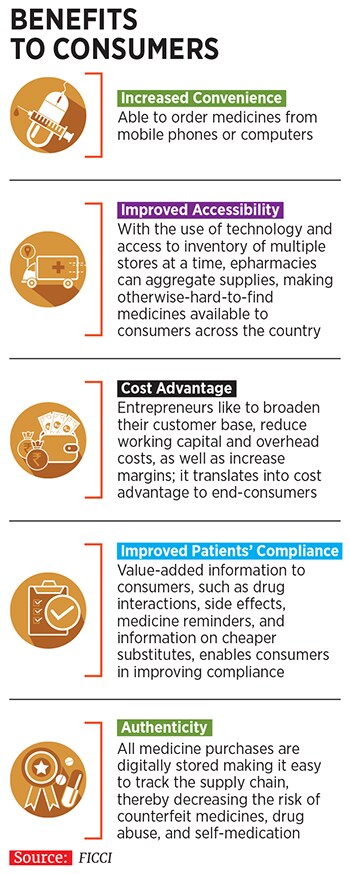

Offers of up to 35 percent off or more on the retail price are de rigueur. As a customer acquisition tool this may be difficult to justify as only about a fourth of customers stay loyal to a single site. While there is a lot of value-add that epharmacies could bring, it remains uncertain whether for now the customer is willing to be swayed by anything except price.

It is hardly surprising then that three years after Parekh launched RxHeal, he is candid enough to admit that “the biggest problem I face is deep discounting. It is not a road I plan to go down for long”. He’s not comfortable burning cash endlessly even though RxHeal has raised some seed funding, it is working on pivoting its business model to steer clear of the cash-burn game.

For now it’s not hard to see why India’s epharmacies are willing to go the extra mile to fight for market share. The Indian pharma industry is extremely profitable for everyone in the value chain—the pharma companies, the distributor and the chemist. This is not a category like mobile phones where margins online on new best-selling models are as less as 5 percent. Chemists work on a 20 percent margin, which is a huge lever in the online world.

In some categories, scale has brought in the hope of even higher margins. Unlike consumer goods or electronics, medicines are not bulky to transport and delivery charges are usually no more than ₹20 for a company that delivers along a pre-determined route every day. Purchases except for the cold, cough, headache variety are almost always pre-planned. For chronic patients suffering from hypertension, diabetes or osteoporosis, medicine is a specialised product where bill sizes invariably total ₹1,500 or above. This constitutes about 70 percent of the market and there are loyal repeat customers. PharmEasy, a three-year-old platform, for instance, claims to have 1 million unique customers with about 35 percent on a regular plan. Their prescriptions are stored online to meet with regulatory requirements.

Why then are epharmacies bleeding and is there a way out? The answer lies equally in reducing discounts and slashing their operational costs. Sripal Bachawat, director, C-Square, a software company, has seen the industry operate up close. His company has developed the software platforms Indian epharmacies operate on. “Instead of thinking like retailers, they (chemists) need to start working like distributors and emulate their business practices,” he says.

Here’s how. Typically, medicine priced at ₹100 packs in a 20 percent margin for the seller and, after that, 10 percent (₹8) for the distributor. The typical distributor serves about 30 chemists a day and spends about ₹20 on each delivery to get it to them. This business mostly works on the daily replenishment model. He gives a 3 percent discount for instant payment and spends 2.5 percent on delivery and administration costs. Depreciation is another 1 percent leaving him with ₹2.40—an Ebitda margin of slightly over 3 percent. Software development expenses are a one-time cost for epharmacies and the asset is depreciated to zero over time.

As the business evolves, there are some epharmacies that are thinking differently and admit that in order to function like distributors they need to partner with retailers rather than thinking of them as adversaries. Kolkata-based SastaSundar Ventures, which runs stores under the Health Buddy brand, provides some clues as to how the business may evolve. The company has tied up with 220 stores in West Bengal and 20 in the National Capital Region. “By working with stores, we have the advantage of getting them to exclusively order through us as well as reducing the headache of managing deliveries,” says Ravi Kant, chief executive of SastaSundar Ventures.

Ravi Kant of SastaSundar Ventures does not want to sacrifice profitability in the rush to expand

Ravi Kant of SastaSundar Ventures does not want to sacrifice profitability in the rush to expand

Image: Subrata Biswas for Forbes India

The company gets a franchisee to rent a store space (branded Health Buddy), usually about 100-125 square feet. The space needed is smaller than regular chemist stores as they don’t need to store medicines on their shelves and the company is able to partner with small entrepreneurs who don’t block capital in keeping medicines. SastaSundar is thinking of this as a pure play retail business where higher throughput instead of higher margins drives profitability. Medicines, packed and labelled, are supplied by SastaSundar from their warehouse with a flat 15 percent discount passed on to the customer. Six percent is shared with the operator of the store.

While it is still early days, there are initial signs that the model could work. After losing ₹2.44 crore in the financial year ended March 2017 the company made a profit of ₹11.32 crore a year later SastaSunder is a listed company with a market capitalisation of ₹310 crore. Even though Kant realises that there is little to prevent others from copying the model, he is clear that he doesn’t want to sacrifice profitability in the rush to expand. “There is enough room for everyone,” he says.

If working to make retail more efficient is the Holy Grail for SastaSundar, others have opted for other paths to growth. “As digital advertising (Google AdWords) is not permitted, we have chosen to go down the information route,” says Prashant Tandon, co-founder of 1mg, whose website received 150 million monthly page views of content every month. The firm uses this to sell medicines as well as keep a track of patients’ illnesses. It may even recommend tests. PharmEasy sends SMSes reminding patients when to take their pills. Both agree that discounts of 15-20 percent are hard to sustain although Dharmil Sheth, co-founder of PharmEasy, says, “In certain categories where we have scale, we are able to procure medicines between ₹60 and ₹72 on a retail price of ₹100.”

The desire to compete on price alone has led to some unscrupulous practices among a few epharmacies. Recently the government of Rajasthan seized a consignment of spurious drugs. According to documents reviewed by Forbes India, Alkem Laboratories confirmed that it had not manufactured the drugs. Two chemists in Mumbai confirmed reports of spurious medicines being sold online. They declined to be named.

One of the quirks of the Indian market is that even generics are branded and what a doctor recommends often depends on the incentives he is given by the pharma company. It is not uncommon to find several medical representatives sitting outside a doctor’s office on any given day. Section 16 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act prohibits chemists from recommending generic names of the same drug. If a doctor prescribes a particular brand the chemist has to fulfil the prescription or advise the patient to go to another shop.

A recent change in the government’s stance is likely to make a substantial dent in the fortunes of epharmacies. Under the government’s Jan Aushadhi scheme, citizens can access cheaper generics through a network of 3,500 pharmacies. The industry hopes that the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, would be amended, allowing it to build a repository of knowledge to suggest a cheaper alternative.

RxHeal wants to become a thought leader in the generics space. Parekh says they can recommend different (cheaper) alternatives down to the same molecule level once the law changes. For now he has scaled back and is conserving capital. RxHeal only takes order on phone and WhatsApp. “This way I know that only the most loyal of my customers are with me,” he says. With a large pie to play for, competing for scale may not be the only way to win in this business.

First Published: Sep 14, 2018, 15:06

Subscribe Now