A stormy affair at Axis Bank

Axis Bank CEO Shikha Sharma's exit has been as stormy as her entry. It also signals a strong message by the RBI to the banking industry

Axis Bank has appointed executive search firm Egon Zehnder to shortlist candidates to replace Shikha Sharma

Axis Bank has appointed executive search firm Egon Zehnder to shortlist candidates to replace Shikha Sharma

Image: Vikas Khot

When Axis Bank Managing Director and CEO Shikha Sharma’s request to curtail the tenure of her fourth term at the bank to six months (now December 31, 2018) from the earlier three years (to end May 2021) was acceded by the bank’s board—after the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) called for a reconsideration recently—it signalled two things. That Sharma had decided she had had enough of the negative news that had come to surround her leadership in recent years. It also sent a message to the banking sector that the RBI will put its foot down when the situation demands.

Sharma’s journey at Axis Bank has been as stormy as her entry in 2009. Sharma, who previously headed ICICI Prudential Life Insurance, entered Axis as an “outsider” with backing from the board. That did not go down well with her predecessor PJ Nayak, who quit in three months before his term ended, as he had wished for an “insider”.

Almost nine years later, Sharma has chosen to cut her own term short, after several issues that have plagued the bank over the last couple of years.

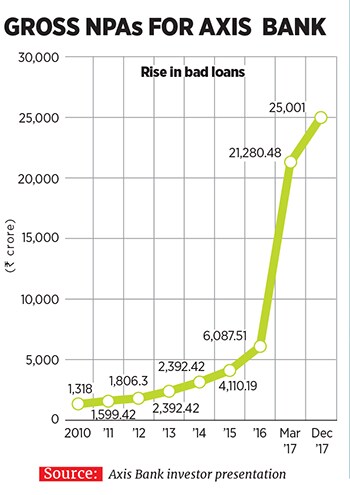

First there were reports of illegal practices by some Axis Bank branch staff during demonetisation in late 2016, followed by divergence in the assessment and reportage of bad loans of the bank against that of the RBI. Then, in December 2017, there were reports of alleged WhatsApp ‘leaks’ of price-sensitive earning data, which market regulator the Securities and Exchange Board of India ordered a probe into.Axis has -- in a bid to lend aggressively to corporates -- has been plagued by a sharp rise in bad loans over the past four years (see chart).

In its latest Q4FY18 (January to March) quarter, Axis reported a net loss of ₹2,189 crore, its first ever quarterly loss since listing at the stock exchanges in 1998.

This loss was due to higher provisioning for bad loans, which came in at ₹7,179.53 crore for the quarter ended March 2018, compared to ₹2,581.25 crore, for the same period a year earlier.

The percentage of bad loans (to gross advances) also jumped, to 6.77 percent for the quarter, from 5.04 percent last year.

This is the part analysts are most worried about. “The next four to five months are crucial. The asset quality of the bank is not comforting. Before Shikha moves out, she needs to sort it out. The new chief must start on a clean slate,” says a banking analyst with a financial services firm.

“The bank will have to continue to deal with its non-performing liabilities (NPL) issues—in which it lies between the good (HDFC Bank, Kotak Mahindra Bank) and the bad (most public sector units). Some NPLs were on account of change in regulations (infrastructure) and others on account of the business cycle (steel), but whatever the underlying cause, these will have to be cleaned up,” says Amit Tandon, founder and MD of Institutional Investor Advisory Services, an independent corporate governance body.

THE RBI MUSCLE

Whether or not Sharma’s early exit has anything to do with the RBI nudge asking the bank to reconsider her term extension, it sets the precedent for more to follow. The RBI has rarely stepped in to determine who heads a bank. The one time in recent history it intervened was when it put pressure on Ramesh Gelli, then chairman and managing director of Global Trust Bank, to quit in 2001, in the midst of the bank’s eroding net worth and reckless lending practices.

However, in this case, the RBI’s decision is not benchmarked against any specific moves or malpractices. This could be a matter of concern for private banks in particular, if their leadership is in trouble. The Chanda Kochhar issue is a case in point. (see box). WHAT NEXT

WHAT NEXT

The Axis Bank board has appointed executive search firm Egon Zehnder to shortlist candidates to replace Sharma. And the possibility of the next leader being an outsider is strong.

Sharma’s tenure has been a mixed bag. The bank did well in terms of growing the balance sheet (₹643,938 crore size as on December 31, 2017, from ₹180,586 crore as on March 31, 2010) and diversifying lending from pure corporates to retail and now the SME segment. As of December 2017, retail loans accounted for 46 percent of its total loan book, compared to 21 percent in June 2009, when she took charge.

But there has been little to cheer about in recent years, barring the Enam Securities acquisition in 2010, which now refurbished as the institutional equities and investment bank Axis Capital, is named in the top equity league tables.

Learning from its recent investment mistakes, the bank has strengthened credit writing and focussed on lending to better rated corporates. The bank’s exposure to top 20 borrowers as a percentage of Tier 1 capital has been declining and stood at 118 percent at the end of Q2FY18, compared to 287 percent at the end of FY11, an Axis Bank investor presentation shows.

Vision 2020 could well mean a greater thrust towards retail and digital banking strategy-wise there is little the bank will need to change.

First Published: Apr 23, 2018, 08:45

Subscribe Now