Has TV Narendran brought Tata Steel out of its lost decade?

The global CEO and MD's efforts and initiatives may have brought the steelmaker back from the brink, even as a steady and sustainable upcycle in prices takes shape

It would be fair to say that the average price [of steel] of the next decade would be higher than that of the past decade: TV Narendran, GLOBAL CEO & MD, Tata Steel

It would be fair to say that the average price [of steel] of the next decade would be higher than that of the past decade: TV Narendran, GLOBAL CEO & MD, Tata Steel

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

In February 2020, with the pandemic still to arrive on Indian shores and media headlines focussed on then US President Donald Trump’s impending visit, TV Narendran, 55, had access to an early warning system none of his Indian counterparts had. The Indian steel maker’s European operations, which had proved to be a millstone around its neck, provided a peek into what a total shutdown would look like. What the global CEO and managing director saw wasn’t pretty, prompting him to swing into action. As infections spread across Europe, necessitating lockdowns, business activity ground to a halt.

Narendran started flagging the business risk on account of the pandemic as early as January. He’d been helming a global steel business that was highly leveraged. A period of no sales had the potential to sink the business.

Sample this: A month of production and no sales meant a cash burn of ₹5,000 crore. That’s more than the annual profit of Titan and half that of Tata Steel in the preceding year. He knew that this won’t be tolerated at Tata Sons, the holding company of the conglomerate comprising 30 major companies across 10 industrial clusters.

Away from the steel mills in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, and Kalinganagar, Odisha, the finance teams at Bombay House, the headquarters of the 154-year-old Tata Group, and One Forbes Building, swung into action. The man responsible for company finances, Koushik Chatterjee, set up a ‘virtual cash war room’. In earlier times, the business would have committed to an expense and the finance team would have been left to decide when to make the payment.

“Typically, at Tata Steel India, generation of cash flow has never been an issue as it is a very competitive business. The key issue, in the past, has been the capital allocation for capex and supporting European business," he explains. Now, his team went to the source of every cash call—procurement, maintenance capex and operations—and took a hard look at whether it needed to be done.

In those months, every business decision was put through the wringer. And while Chatterjee had to go out and raise funds—gross debt rose from ₹104,000 crore to ₹118,000 crore in the first quarter of FY21—the strategy paid off. As sales rebounded in June, the company ended up with a free cash flow of ₹1,000 crore in that lockdown-marred quarter.

It was an astounding feat for a business that had seen its sales shrink by a third that quarter and had high fixed costs. Just as it had demonstrated with the Bhushan Steel acquisition in 2018, there was a new urgency at the company to get things done.

Aggressive. Assertive. Confident. These are words increasingly entering the analyst vocabulary to describe India’s oldest steel business. After almost a decade, the business has a veritable spring in its step. A lot has to do with steel prices that are touching new highs. They give the company the cash flows to plan expansions, pare down debt and return money to its parent and shareholders. But over the last five years, it has also moved to systematically de-risk its business from the European operations, which took shape via the roughly $12 billion acquisition of Corus in 2007.

In India, Tata Steel’s 20 MT capacity is spread over three sites: Jamshedpur, Dhenkanal (Odisha), and Kalinganagar (above). The company is adding 5 MT capacity in Kalinganagar

In India, Tata Steel’s 20 MT capacity is spread over three sites: Jamshedpur, Dhenkanal (Odisha), and Kalinganagar (above). The company is adding 5 MT capacity in Kalinganagar

Tata Steel is no longer seen as losing out to rival JSW Steel. At 20 million tonnes (MT) in domestic capacity, it is now just a shade behind JSW’s 22 MT. This new phase of growth has also come about with a lot more financial discipline. Even before the present uptick in steel prices, reducing debt by billion dollars a year was a stated goal. “Chandra (Tata Sons Chairman Natarajan Chandrasekaran) is very cash-focussed and he is pushing it hard. In capital-intensive businesses, you focus on Ebitda—perhaps the best indicator of a business’s earnings—and not on cash," says Narendran pointing to a change in thinking.

Over the last year, the improved financial metrics have been rewarded by investors. While the benchmark NIFTY Metal index was up by 151 percent in 2020, Tata Steel’s market capitalisation has moved up by 256 percent to ₹141,000 crore, making it India’s second most valuable steel company. The average return on equity has improved from 4 percent over the last decade to 11 percent in the financial year ended March 2021.

What excites market watchers is that the business should be able to expand without expanding its balance sheet. “[Going forward] Tata Steel should be able to sustain a higher level of credit metrics irrespective of where you are in the cycle," says Neelakantan Gopalakrishnan, director at S&P Global Ratings.

What excites market watchers is that the business should be able to expand without expanding its balance sheet. “[Going forward] Tata Steel should be able to sustain a higher level of credit metrics irrespective of where you are in the cycle," says Neelakantan Gopalakrishnan, director at S&P Global Ratings.

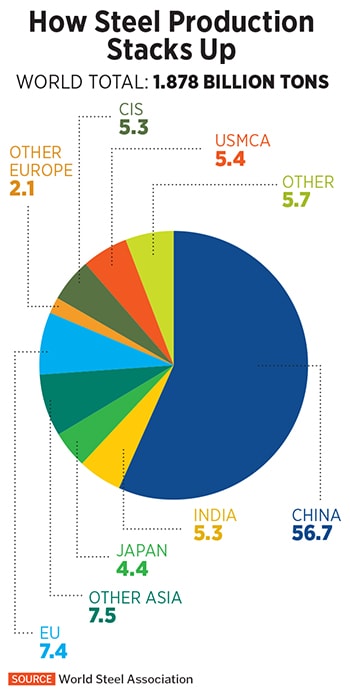

For now, this is what excites investors about the Indian steel business. The industry is rapidly consolidating among Tata Steel, JSW Steel, SAIL, ArcelorMittal and Jindal Steel and Power. Greenfield capacity will be hard (but not impossible) to come by once brownfield expansions are done over the next five years.

There’s even talk about steel doing what cement has done where valuation multiples have moved up rapidly since 2013. Investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala in a recent interview to CNBC-TV18 questioned why steel stocks are trading at 7 to 10 price multiples when cement stocks are trading at 30 to 40 price to earnings multiples. As earnings become more predictable for the industry, the hope is that valuations will also catch up. The one important difference is that unlike cement, steel is a globally traded commodity. Prices are controlled by what happens in China.

Tata Steel’s prospects are as much dependent on China as they are on what it does in the Indian market.

China, Corus and the Hunt for Scale

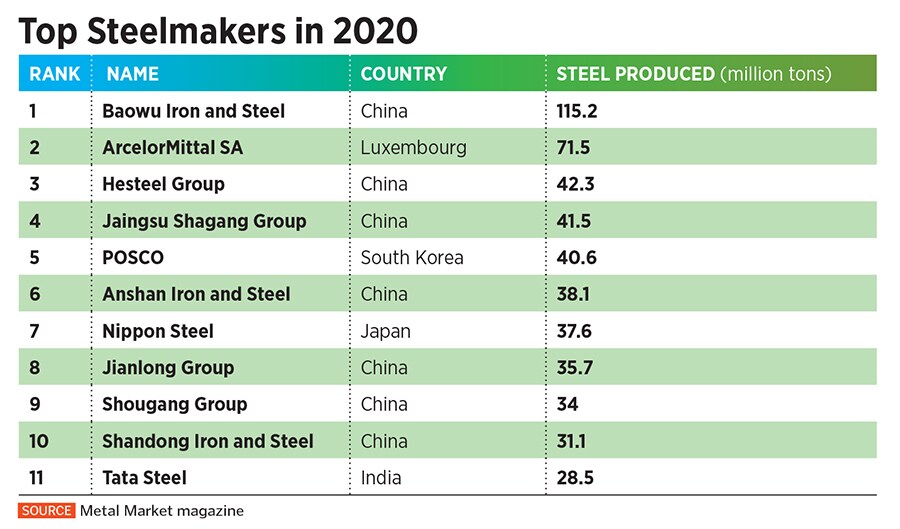

It’s hard to overstate the outsized impact that China has had on the global metals business for the last two decades. As the country rapidly industrialised, it went about adding capacity at a furious pace. By 2004, with a production capacity of 200 MT, it was the world’s largest steel producer and an important buyer of iron ore and coking coal. By 2015, that number would rise to a billion MT and accounted for 62 percent of global capacity.

Demand from China also led to a commodity super cycle, the likes of which the world had never seen before. Iron ore prices rose 10-fold to $200 a tonne in that decade. It also spurred a mergers and acquisition cycle in the industry as new producers flush with cash went shopping for distressed steel mills and mines. It was here that Tata Steel found itself at a disadvantage on account of a lack of scale. In 2005, all it had was a 5 MT plant in Jamshedpur (India’s total steel capacity in 2005 was 43 MT) while rivals like Mittal Steel were closing in on 100 MT with the takeover of Arcelor.

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

“If someone who is 100 MT is buying coal and iron ore and ferro alloys and you are 5 MT and buying the same stuff, you are at a disadvantage," says Narendran. At the same time, the company had signed agreements with the state governments of Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh for setting up plants, but nothing had come of them. All it had was a small ₹560 crore acquisition of Singapore-based NatSteel in 2004.

The hunt for scale took the company to Europe and the acquisition of Corus Group plc in 2007. Overnight, it catapulted to 27 MT with plants in India, the United Kingdom and The Netherlands. While Narendran parries a question on whether the acquisition was a mistake, he does point out that in its first year, the business made a billion dollars in profit and investors couldn’t stop commenting on the fortuitous timing of the acquisition.

But post the Lehman crisis in 2008, the steel cycle reversed and, while Chinese demand declined, regions and municipalities across the country kept their plants running in order to keep workers employed. And exports stayed high—in 2015, China exported 120 MT of steel out of a capacity of 1 billion MT. That has since fallen to 60 MT.

Efforts by the leadership in Beijing to cut capacity proved unsuccessful. Malay Mukherjee, the former CEO of ArcelorMittal, who was on the board of Hunan Valin Steel, recalls a conversation where the company was to shut down three 500 cubic metre blast furnaces as they were polluting. So they went and built a new one and when it was operational, kept the old one running anyway as they rightly concluded that the bosses in Beijing would have forgotten about it.

Efforts by the leadership in Beijing to cut capacity proved unsuccessful. Malay Mukherjee, the former CEO of ArcelorMittal, who was on the board of Hunan Valin Steel, recalls a conversation where the company was to shut down three 500 cubic metre blast furnaces as they were polluting. So they went and built a new one and when it was operational, kept the old one running anyway as they rightly concluded that the bosses in Beijing would have forgotten about it.

Then there was the issue of mothballed capacities primarily in Europe coming onstream the moment prices would rise. This, coupled with Chinese exports, kept a cap on global prices and restricted the profitability of the industry.

As the world economies opened up post-pandemic, a confluence of three factors kept prices elevated. Industry participants hope that they prove to be long lasting. First, the geopolitical tensions between China and Australia have meant that the country is importing expensive iron ore and coal from Mongolia and Brazil. This has increased the cost of production for Chinese mills making their exports unviable. It remains to be seen how long this continues.

Second, infrastructure spending planned by Western economies should keep demand elevated. “Once spending on infrastructure starts, it usually lasts for three to five years," says Mukherjee.

Third is the carbon story playing out around the world. China has committed to net zero emissions by 2060. The question being often asked in Chinese policy circles is why does the country need to import iron ore and coal and make steel, which leaves a carbon footprint, only to export it. In April, China’s National Development and Reform Commission said it would launch an investigation on why steel capacity cuts planned since 2016 had not been implemented.

Chatterjee of Tata Steel also points out that this time around, despite high prices, not all mothballed capacities in Europe have resumed as the carbon costs for the marginal capacities would be material given the level at which the ‘European Union Emissions Trading System’ (EUETS) prices are trending. In March, Nippon Steel said it would cut 20 percent of its 54 MT capacity as it prepares for a zero carbon future.

As it prepares for the next decade, Narendran is confident of prices being higher. “It would be fair to say that the average price of the next decade would be higher than that of the past decade," he says. Accordingly, he’s got in place plans to expand capacity to 25 MT by 2025 to take advantage of rising demand from India.

[qt]With every rupee that we earn, the first one billion (DOLLARS) will go for debt repayment. Only critical and maintenance capex come before that."

Koushik Chatterjee, Executive Director & CFO, Tata Steel[/qt]

The India Plan

In India, Tata Steel’s 20 MT capacity is spread over three sites: Jamshedpur, Kalinganagar and Dhenkanal (Odisha), the site of the plant acquired from Bhushan Steel. This is where it could have a significant advantage over its peers in the years to come. While the company is adding 5 MT in Kalinganagar, it can easily add another 8 MT at that site and an additional 5 MT at Dhenkanal and 3 MT at Jamshedpur taking total capacity to 40 MT.

This is not an option available with competitors. JSW’s committed expansions should take it to 30 MT while ArcelorMittal has scope for doubling its capacity to 16 MT at its Hazira site based on the availability of gas. SAIL has almost infinite scope to expand as each of its plants has several thousand acres to spare for expansions. Thereafter, it is either greenfield expansion or acquisitions that come into play.

The history of setting up greenfield sites in India hasn’t been pretty. Land acquisition troubles have led companies to abandon their plans. After over a decade of trying to set up a plant in Odisha and Karnataka, POSCO exited the country in 2017. It took Tata Steel 10 years to set up its Kalinganagar plant after it signed the memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Odisha government in 2004. Mittal Steel signed MOUs with Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh, but couldn’t get a plant off the ground. “It is certainly longer, more painful and a test of patience as far as setting up greenfield plants in India is concerned," says Chatterjee.

On the acquisition front the company is interested in assets in the long products space as flat products constitute 80 percent of their product basket. They have put in an expression of interest for Neelachal Ispat, and if RINL (Vizag Steel) were to come up for sale they would be interested in it as well.

On the business front, Tata Steel’s aim is to make sure that value-added products account for an increasing share of revenue every year. Analysts are quick to point out that there are varying definitions of ‘value added’ and every company defines them differently, but Narendran clarifies that anything that is technically challenging is what he considers value add. The company now has a 50 percent-plus share in the market for automotive steel and 30 percent in products for the oil and gas industry (some products are still in the certification stage).

As India industrialises, per capita steel consumption is slated to go up and a B2C presence will prove to be important. Per capita consumption in India stands at 64.2 kg per person per year against the global average of 229 kg. Here the nascent B2C and solutions business holds promise for the company and its competitors alike.

These are roofing sheets, car port designs, railing designs, gate designs and so on. Sold through Tata Aashiyana, this business saw revenues double to ₹726 crore in FY21. The plan for FY22 is to take it to ₹1,500 crore. “These are typically sold on a per piece basis rather than on weight, so the margins are much better," says Amit A Dixit, director at Edelweiss Securities. There are also attempts at branding home solutions through the Tata Nest-In brand. Doors made from steel are sold as a solution to wooden doors that are prone to termites. And finally, even commodities like rebars are branded through Tata Tiscon. The company is marketing these products aggressively. This reporter started seeing Google ads for Tata Steel’s branded products in web searches while researching the story.

The Road Ahead

The Road Ahead

As Tata Steel pivots once again to an Indian company, its European worries seem to be behind it. The business has been separated into Tata Steel UK and The Netherlands, and the company says it is not actively looking for a deal (in the past, two deals with Thyssenkrupp and SSAB have failed on account of approval not coming in from the competition commission.)

The UK operations have been shrunk from 10 MT to 3 MT and the company says it is in talks with the government on how to keep operations going. A competitor who Forbes India spoke to says it is unlikely there will ever be a buyer for that plant on account of the way it is structured.

There is more hot metal capacity than steel-making capacity. There is more steel-making capacity than rolling capacity. And there is more rolling capacity than there is capacity for value-added products. “Hot-rolled coils are not something you can make in a high-cost environment and hope to survive," he says. The company can’t shut down operations at Port Talbot in Wales due to high retrenchment costs. The Netherlands plant could someday see a suitor as it is a coastal unit, but it is now amply clear that the buyer would have to be from outside Europe. Still, Tata Steel’s Indian cash flows no longer need to support European mills.

In India, the company could expand faster through the electric arc furnace route. As the quantum of steel in India increases, so will the amount of scrap available for melting. The NatSteel plant in Singapore has used this route to expand. Scrap is sourced from dealers, cleaned, rolled and fabricated and then sold as value-added products. In Brazil, Gerdau, which started as a nail factory, has used this route to expand to 26 MT across the Americas. In the United States, Nucor has also installed electric arc furnaces.

The advantage is two-fold. First, the carbon intensity of such steel is 20 percent of what it would be if made in a blast furnace. Tata Steel is the first steelmaker to have set up operations in Rohtak, Haryana, and plans to use this route to expand in the north, west and south of India. These are typically 1 MT units built over 100 acres. There is no need for a coke oven, a sinter plant or a pellet plant. Second, the capex intensity is much lower. “You can easily build 5 to 10 of these across the country pretty quickly," says Narendran.

A little more than halfway into his second term as managing director, Narendran continues to stress that the business needs to be made more cost competitive. He’s keenly aware that in 2030, Tata Steel’s iron ore mines will be auctioned again and it could well lose its cost advantage over its peers. The company launched a Shikhar 25 programme in 2015 with the aim of getting to 25 percent Ebitda margins with raw materials at market prices.

At ₹30,000 to ₹32,000 per tonne Ebitda, Tata Steel is on track to have a blowout first quarter of the current fiscal. In fact, it may even end up reducing debt by a billion dollars in April-June. “With every rupee that we earn, the first one billion [dollars] will go for debt repayment," says Chatterjee. “Only critical and maintenance capex come before that." Balancing a leaner balance sheet with growth will be a key challenge and for now, it looks like the business has a fair chance of achieving that.

A clear signal has been sent out to the investor community that reducing debt is priority. Gopalakrishnan of S&P expects the company’s S&P-adjusted debt to reduce to about ₹70,000 crore by the end of fiscal 2023. “The main issue for steel companies’ ratings has been the volatility in earnings. And now there is a real chance that some of that volatility in credit metrics could be reduced with lower debt," he says.

If that happens, brace for a once-in-a-decade rerating of the business and the industry.

First Published: Jul 07, 2021, 11:50

Subscribe Now As soon as the pandemic hit, Koushik Chatterjee, the man responsible for company finances, set up a ‘virtual cash war room’

As soon as the pandemic hit, Koushik Chatterjee, the man responsible for company finances, set up a ‘virtual cash war room’