Brand IIMparity: Assessing the new IIMs

The new IIMs have come a long way since they first took flight a decade ago, but still struggle to attract quality students and faculty. How does this impact the brand?

IIM-Rohtak has ₹46 crore pending from the ₹333 crore budget, but will require significant additional funds to complete the campus as planned

IIM-Rohtak has ₹46 crore pending from the ₹333 crore budget, but will require significant additional funds to complete the campus as planned

Image: Madhu Kapparath

It’s as easy as A-B-C. Any management student in India can tell you that.

For generations now, the hierarchy of the coveted Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) has been denoted by the simple strain of the alphabet. By value of prestige, the chain goes: IIM-Ahmedabad or IIM-A IIM-Bangalore or IIM-B and IIM-Calcutta or IIM-C. That sequence remains dominant even today, almost six decades after the first IIMs were established in Ahmedabad and Kolkata in 1961, and now when 20 IIMs stand ground.

This is part of the problem.

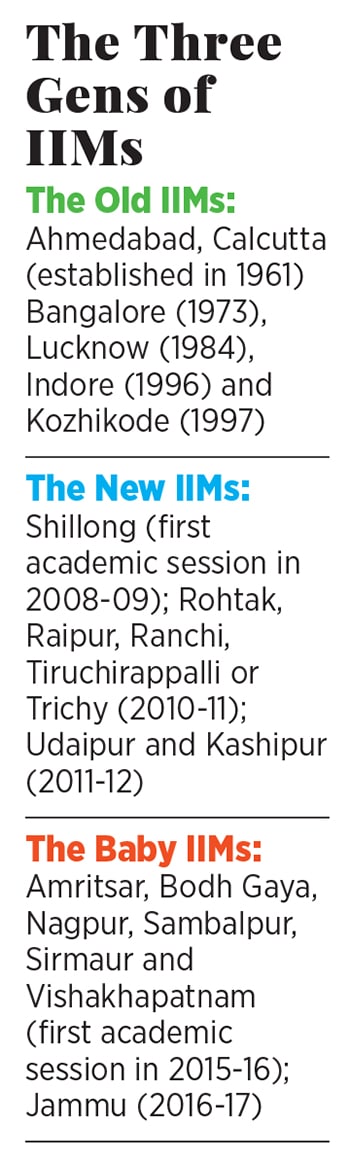

The IIMs can be categorised into three generations. The first set, referred to as the ‘older IIMs’, are IIM-A, IIM-C (established in 1961), IIM-B (1973), IIM-Lucknow (1984), IIM-Indore (1996) and IIM-Kozhikode (1997). The hierarchy remains largely sequential, in order of establishment.

Then comes the second-generation, colloquially called the ‘new IIMs’. The previous government pushed for the expansion of quality management institutes, setting up seven new IIMs about a decade ago—these are at Shillong (which began its first academic session in 2008-09) Rohtak, Raipur, Ranchi, Tiruchirappalli or Trichy (functioning since 2010-11) and Udaipur and Kashipur (started from academic year 2011-12). All of these were until recently operating from makeshift campuses.

Even before this fledgling generation of IIMs could be fully functional, a third generation of IIMs was set in motion in 2015-16. The six ‘Baby IIMs’, as they are called, have been established at Amritsar (Punjab), Bodh Gaya (Bihar), Nagpur (Maharashtra), Sambalpur (Odisha), Sirmaur (Himachal Pradesh) and Vishakhapatnam (Andhra Pradesh). A seventh was later announced at Jammu, which started its academic sessions a year later.

While it is too soon to assess the quality of the baby IIMs, which still work out of makeshift campuses and don’t attract the same level of students as the previous IIMs would, it’s a good time to take stock of the new IIMs, a decade after the first began operations.

Money Matters

Over the past few months, all the second-generation or new IIMs have shifted base to permanent campuses, with the exception of IIM-Ranchi. Each new IIM was allocated ₹333 crore to build their campus, and the government was contemplating granting them an additional ₹300 crore to each to tide over the rising expenses. However, recent news reports say the Centre has decided against this additional funding as it wants the institutes to be self-sufficient.

The Indian Institutes of Management Act 2017, which came into effect in January 2018, granted autonomy to all 20 IIMs, so that they can appoint their own directors, decide their own fee structure and award degrees instead of diplomas, among other features. Reports say that in the spirit of autonomy, the government would like for the IIMs to raise their own funds too.

“This works in the case of the older IIMs, which generate their own revenue and can manage their operational finances,” says P Rameshan, professor at IIM-Kozhikode and former director of IIM-Rohtak. “But, for the newer IIMs, most of them have only completed their first phase of construction. An equal amount will be needed for their next phase.”

IIM-Udaipur and IIM-Trichy have spent the entire ₹333 crore and used up additional funds too the other new IIMs are likely to receive the pending amount, which ranges from ₹27 crore to IIM-Kashipur to ₹263 crore to IIM-Ranchi, which acquired land for its permanent campus only in 2016.

“While we have received no official intimation about this, we have heard it might be a possibility,” says Dheeraj Sharma, director, IIM-Rohtak. “At Rohtak, we have completed Phase 1 of construction at the permanent campus, but have Phase 2 and 3 remaining. I would urge and request the government to reconsider capital funding.”

IIM-Rohtak has about ₹46 crore pending from the original ₹333 crore budget, but estimates that it will require significant additional funds to complete the campus as planned. Sharma says that 50 percent of the campus is now complete.

[qt]We have completed Phase 1 of construction at the permanent campus, but Phase 2 and 3 remain. I would request the government to reconsider capital funding.”

Dheeraj Sharma, Director, IIM-Rohtak[/qt]Image: Madhu KapparathFor any IIM, the expenses are of two kinds—capital and operational. “If the IIMs are moving in the line that they were envisioned, a mid-sized IIM would require ₹30 crore to ₹35 crore for annual operational expenses,” says Sharma. “If they expand to a batch size of 500, and charge a moderate ₹7 lakh as fees, the flagship PGP programme should be able to cover operational and recurring expenses. However, capital expenditure is the problem.”

IIM-Rohtak, for instance, requires more dormitories, class rooms, faculty offices and faculty residences to reach full capacity. IIM-Udaipur shifted to its permanent campus almost two years ago, but still doesn’t have faculty housing entirely ready—a few members have moved in on the campus only recently. IIM-Raipur’s library is not fully functional and their sports block is under construction.

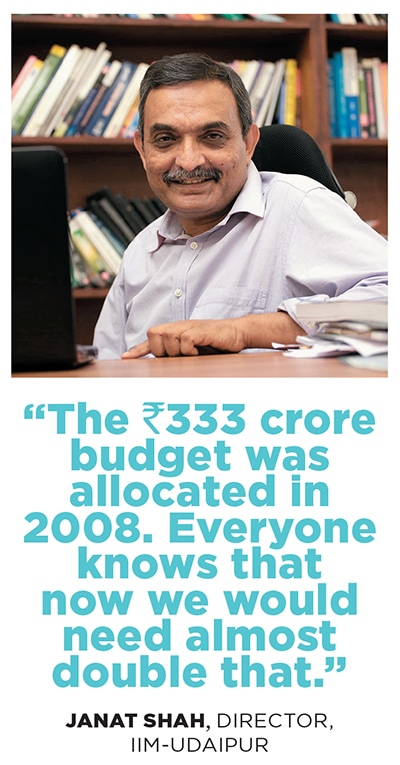

“The ₹333 crore budget was allocated in 2008,” says Janat Shah, director, IIM-Udaipur. “Obviously, everybody, including the agency that prepared the original report, knows that now we would need almost double that. We decided to work with a larger scope than originally planned and took a greater chunk in Phase 1 than other institutes have. This is why we have utilised the entire fund that was allocated.”

Shah says a larger discussion is on about the way that higher education financing will take place henceforth, especially since the Hefa (Higher Education Financing Agency) was incorporated in May 2017. Hefa is a joint venture between the ministry of human resource development and Canara Bank, with an agreed equity participation of 91 percent and 9 percent, respectively. It aims to help develop India’s top-ranked institutions (IITs, IIMs, NITs, AIIMS) by investing in their academic and infrastructure quality. The key here is that Hefa will provide loans, not grants, effectively changing the way higher education is financed.

“We have already increased our first-year batch sizes for the PGP programme to 260. IIM-Ahmedabad and Calcutta took 40 years to reach those numbers,” says Shah. “Obviously, times are different, but we are proud of what we have achieved. The government has been very generous thus far, and we have been able to invest heavily in a strong research programme. If they continue to support us, we can achieve our targets and increase batches to 500 students in seven years.”

Shah says that if the government funding doesn’t come through, the institute would use the combination of a loan, their own parked funds and reach out to philanthropists. “Our board is reasonably confident that this will work,” he says. “We have built a reputation and have tangible data—including our research metrics, IPRS rankings and certifications—to justify that.”

According to IIM-K’s Rameshan, increasing fees is a short-term option to raise funds, but not sustainable. “I don’t think even IIM-Ahmedabad or Bangalore would be able to sustain on high fees,” he says. “Beyond a certain point, students would prefer to go abroad for an MBA.”

Increasing batch sizes would be another fix, but most IIMs don’t have the infrastructure to support this. “IIMs can use executive education as a revenue stream, as a lot of corporates are willing to invest in this,” says Rameshan.

Long Road Ahead

While finances may become an obstacle, the new IIMs struggle with various other challenges. Attracting quality faculty is a prime hurdle.

“Some faculty is good, but some not-so-good,” admits Sarthak Navalakha, a first-year student at IIM-Raipur. “It’s difficult to attract guest faculty. You need budgets for that. We know we’re not IIM-A, B or C, so we set our sights accordingly. We have a good reputation in Chhattisgarh, but others don’t know much about us.”

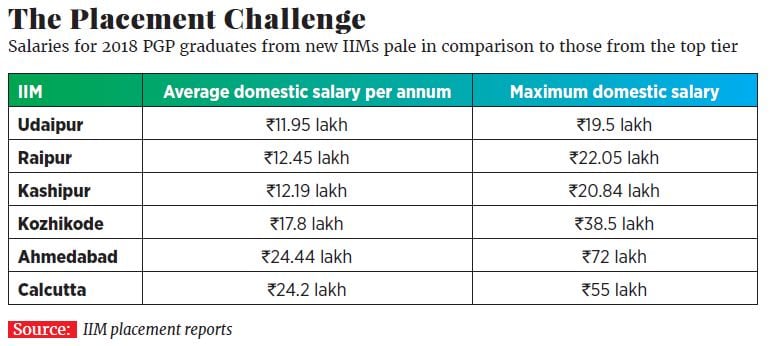

Placements is another challenge, but experts say the new IIMs have enjoyed a reasonably good trajectory over the years. “You can’t compare them to the old IIMs, but they’re doing a decent job,” says Ankit Doshi, founder, InsideIIM.com, a portal to help students make the right B-school choices. “A graduate from IIM-Raipur or Ranchi could expect a salary package of at least ₹10 lakh to ₹12 lakh, which is good compared to the Indian population at large.”

For reference, for the flagship PGP Management programme, at IIM-Udaipur, the average domestic salary in 2018 was ₹11.95 lakh, and maximum ₹19.5 lakh. At IIM-Ahmedabad, the average was ₹24.44 lakh and the highest ₹72 lakh (see chart).

Location can be an obstacle for placements as well. “IIM-Kashipur is close to the mountains, which is an advantage in many ways but definitely a disadvantage when it comes to recruitment,” says Shefali Kushwaha, an IIM-Kashipur graduate of 2017, who now works for the Swachh Bharat Mission. “I remember doing placement interviews over Skype. Many good companies with deep knowledge know that there is a huge difference between Ahmedabad and Kashipur. While they may offer a package of ₹20 lakh to someone from IIM-A, an IIM-Kashipur graduate might get about ₹11 lakh for a similar position.”Kushwaha was one of 16 girls in the batch of 120, a diversity trend that has been a concern for the IIMs, old and new, through generations. Certain IIMs have awarded extra points to female applicants in a bid to increase diversity. Kushwaha says the batch after her saw about the same ratio, and in the one after that, the number of girls dipped further to 10.

“I don’t think gender diversity points are fair to all applicants, as it might lead to a drop in the quality of students,” she says. “Institutes perhaps need to do better outreach programmes to encourage more girls to join.”

Student quality at the new and baby IIMs is a definite concern too. “At IIM-A, B, C, the cut-offs are close to 99th percentile in the Common Admissions Test (CAT), while at, say, Kashipur, this is about 94th percentile. The difference is lakhs of students,” says Kushwaha.

The pool of qualified undergraduate students is also very small, says Doshi. “In most other countries, undergraduates get the sort of jobs that IIM graduates do. But in India, companies want another qualification because our undergraduate programme is notoriously weak. The IIMs then become like finishing school.”

“We have seen that this generation, instinctively born to live with technology and many of whom have lived secluded lives with both parents working, is inwardly bound. Its ability to cope with onerous academic and placement processes is lower than that of previous years,” says Sharma of IIM-Rohtak. “It’s a dramatic change, and attracting the right students is a problem. We need to reinvent the CAT system itself, which is more an exam for deselection rather than selection. Instead, we have to get into recruitment mode.”

Sharma says that through active outreach programmes, they can try and get the right set of people from other countries too, at least Saarc nations to begin with. “It will help with regional-global diversity, which is a good place to start,” he says.

The new IIMs compete for quality students and faculty not just with the older IIMs, but with other top private B-schools too. “Last year, a student converted IIM-Jammu and IIM-Nagpur,” says Jaimin Shah, academic head at CPLC, a leading coaching centre for CAT, which holds the ticket to the IIMs. “He attended classes at IIM-Nagpur for a few days, but saw that its campus was not complete, and lectures were being randomly cancelled. Overall, he thought it to be in a bit of chaos. Eventually, he came back to enrol at Sydenham College in Mumbai.”

“When it comes to final decision-making, students typically look at opportunities after the MBA, and compare them based on placement reports,” says Vinayak Kudwa, chief mentor at IMS, another CAT coaching institute. “They look at fees, location and additional parameters related to their specific field of choice. We have found that students with more work experience would end up selecting a more established private B-school over the new IIMs, while freshers may choose the latter.”

The baby IIMs, he adds, are typically back-ups, and enlist weaker students. “Schools such as ISB and XLRI are considered far superior to the new IIMs,” says Doshi of InsideIIM.com. “Tiss and JBIMS also have strong alumni networks. Most of these schools are at least two or three decades old. The quality of a B-school is determined by various things, and the alumni network is one of them. Even in the second rung of colleges, more often than not, applicants would forego an IIM-Sambalpur or IIM-Sirmaur for an IMT-Ghaziabad or a MICA.”

Instead of making new institutes, he adds, the government could focus on helping established ones such as IIM-A increase their capacity. “Why are they producing only 400 quality graduates when they could have the power to produce as many as a Harvard Business School?” he asks.

Moreover, rising fees are also a factor. Doshi says that when he graduated from IIM-Indore in 2011, the total number of students in his batch was 140. “Now, that number has gone up to 700,” he says. “Fees have almost doubled. Ten years ago, you could graduate from an IIM with ₹5 lakh. Now, IIM-A charges more than ₹20 lakh, and a new one anywhere between ₹10 and ₹12 lakh. So the return on investment for an IIM grad will take longer it will typically take a few years to make that back.”

Brand IIM

What does this mean for Brand IIM? Does it still hold the same prestige?

Yes and no, say experts.

“I don’t think the brand matters anymore, what matters is how an institute is executed,” says Doshi. “A new institute needs more than just financial support. A lot of politically motivated decisions are taken when IIMs are opened in certain locations, which do not have the infrastructure to support it. Eventually, it finds it difficult to become world class and slips into mediocrity. In such cases, I don’t think people would choose such an institute only because it is an IIM, and not, say, an XLRI.”

“Within IIMs, there are various tiers and this is healthy,” says Shah of IIM-Udaipur. “You should have to earn the tag. But on the whole students know that there will be minimum infrastructure and a certain level of quality. The way the government invests in an IIM, very few private institutes can match up. Even the new IIMs have access to resources from the older ones, and recruiters understand the importance of this. The fact that we never have to worry about making a profit makes it clear that we won’t do anything to hurt our quality.”

It isn’t all about competition either, he adds. “If we take the 20 IIMs and 15 of the top private B-schools, we can really focus on making India the hub of quality management education at a moderate cost,” he says. “The centre of economic activity is shifting to China and India, and if we build international standards of infrastructure, we can really capitalise on that. India could become the epicentre for management in this part of the world, and the IIMs can be at the centre of that.”

First Published: Jan 09, 2019, 11:19

Subscribe Now