Meet Asia Pacific's most ordered dish: A veg hot dog in Indore

How Johny Hot Dog, an unassuming street food outlet in Indore, serves up the most-ordered dish on Uber Eats in all of Asia Pacific—a vegetarian hot dog

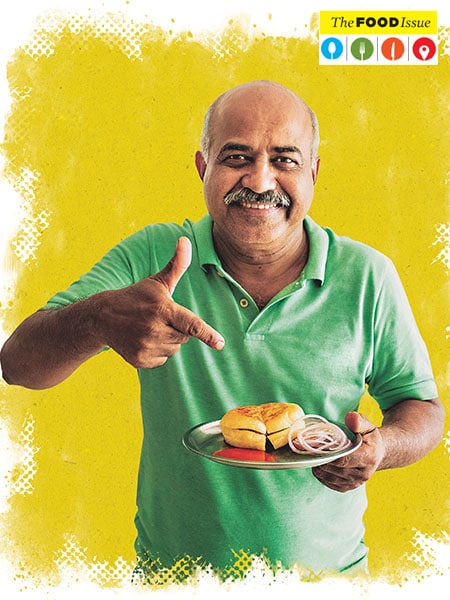

Image: Sakshi Parikh for Forbes India[br] Burger King. McDonald’s. Domino’s. And then a small wonder.

A string of global bigwigs commanded a big bite of the first ever Uber Eats APAC Restaurant Partners Awards 2019. Held in Hong Kong as part of the Uber Eats Future of Food Summit in July, the final award of the night dished up a moment of surprise: The ‘Most Popular Menu Item in Asia Pacific’ was not the Big Mac or pepperoni pizza it was a vegetarian hot dog from Johny Hot Dog (JHD)—a 120-sq-ft stall in the small city of Indore, run by a 60-year-old, unassuming man who had stepped on his first international flight to accept the global recognition.

Dadu, as Vijay Singh Rathore is fondly known in his city, gingerly walked on stage dressed in a baggy suit, visibly overwhelmed and teary-eyed. A slight, balding man with a greying moustache and eyes that smile, Rathore is the quintessential Indian grandfather, fitting to his moniker. He speaks no English. As a host of people come up to congratulate him, he mumbles, smiles and joins his hands, letting his friend (who travelled with him since he was uncomfortable making the trip alone) do the talking.

We meet again a month later, this time on his home turf: Indore. Now dressed in an apple-green T-shirt and casual khakhi pants, Rathore is more at ease. I reach the stall at about 11.30 am, after the breakfast rush has wound down. But the lunch hour is about to begin and people are already lining up.

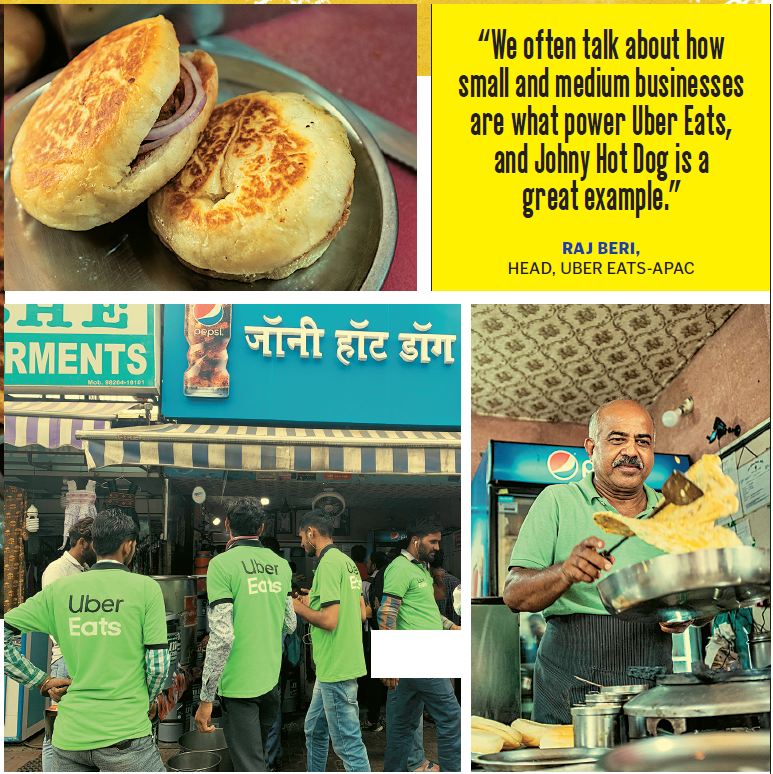

JHD is one of the many roadside stalls across Chappan Dukan, a food bazaar with a long line of street food vendors. As the crowd swells through lunch time, it’s obvious which is the most popular stall—so much so that a smattering of Uber Eats drivers, wearing their signature bright green, is visible milling about across the street, waiting until the next order for JHD beeps on their location-based apps. JHD caters to 3,000 Uber Eats orders a day on average, going up to 4,000 on weekends.

Half of the store is partitioned into a delivery counter, especially for Uber Eats riders, and stacks of water jugs are kept alongside for them to quench their thirst, gratis. JHD has no seats and little space to chat, so I sit down with Rathore and his son, Hemendra Singh Rathore, at a restaurant around the corner that is not yet open. We start at the beginning: How did someone who has had little interaction with American culture invent a version of the hot dog, back in the ’70s?

The making

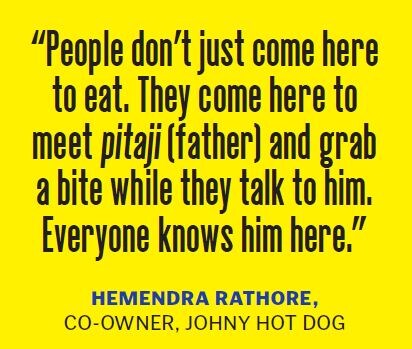

To be sure, JHD’s version of the hot dog is akin to the American variety only in spirit—using sliced bun bread that wraps in a filling. Its shape, however, doesn’t resemble the sausage at all… it is more like a flattened burger, or a fluffy, rounded sandwich.

“We had a cinema hall here that would play only English movies during my childhood, and they would sell such hot dogs,” says Rathore. “A lot of people here have learnt English by going there each night. Everyone would gather there after their work for the day was done, and we would often get a snack. That theatre shut down in the ’70s, taking its hot dogs with it.” JHD dishes up about about 4,500 hot dogs a day[br]In the late ’70s, Rathore, one of eight siblings and the son of a farmer, did various odd jobs at local tea stalls. “Once I had about ₹500 saved up, I told my father I would like to do something of my own,” he says. “My mother would cook for a living. I would watch her and think I could do that too. I always thought this was the line for me, because farming was difficult in those days. We barely had electricity or a motor… we were solely dependent on the monsoon.”

JHD dishes up about about 4,500 hot dogs a day[br]In the late ’70s, Rathore, one of eight siblings and the son of a farmer, did various odd jobs at local tea stalls. “Once I had about ₹500 saved up, I told my father I would like to do something of my own,” he says. “My mother would cook for a living. I would watch her and think I could do that too. I always thought this was the line for me, because farming was difficult in those days. We barely had electricity or a motor… we were solely dependent on the monsoon.”

With his mother’s help, Rathore developed the hot dog recipe—thick, soft, flat bread sourced from a bakery, with a tikki or cutlet inside. The vegetarian version involves a potato cutlet. All variants have tikkis that are roasted, not fried. “For us at home, we didn’t know how to eat these things. We ate mostly jowar and bajra… if we got wheat roti, it would be a festival,” he smiles. “But people gradually became aware of the hot dog, and came to us because it was fresh food, light on the stomach and nutritious, especially for the college students around. This is what still drives us, as it is a meal that is appropriate for breakfast, lunch, tea time or dinner.”

Rathore set up the shop “in 1978 or 1979—some time after the Emergency”. Most of the other stalls across the street bear the owner’s name—Vijay Chaat House, Jain Sweets and so on. “I couldn’t call it Rathore Hot Dog, as it doesn’t sound right. Bread is not part of our culture. So I came up with Johny, and people around seemed to like it,” he adds.

JHD began with three items on its menu and it is the same today, 40 years later. The three-line menu includes a mutton hot dog, the egg ‘benjo’ (a misspelt version of the British ‘egg banjo’, or a sandwich featuring runny egg), and the hot-selling veg hot dog. “The community here was mostly vegetarian when we started out,” says Rathore. “Now, more people eat meat, and as people are becoming health conscious, the egg variety is picking up too. When we started, the egg benjo would be priced at just 10-12 paise, but still there would be little demand for it.” The other items would cost 65 paise each now, they are priced between just ₹25 and ₹30. “It embarrasses me to even charge that much,” he says. “But our costs have gone up too.”

Business had been running smoothly through the years, driven largely by students. Competition has stiffened, of course, even as big players like McDonald’s have set up shop in Indore. “Yes, competition is massive and we have to keep evolving with time,” admits Rathore. “We have upgraded our ingredients. For instance, earlier we didn’t even have refined oil, but now we use the best ghee. But we are not even in the realm of competition for companies like McDonald’s. Our advantage will always be that we serve non-processed, non-fried food that is healthy and quick to digest.”

Demand has only increased over the years. When it started, JHD would open only at 4 pm, but now work begins at 5 am and the outlet opens at about 8 am.

“Now, many of my clients, who were children when we started, visit with their grandchildren,” says Rathore. “Our customers are our biggest stars—there are many who come 20 days a month, sometimes eating here twice a day. We are fortunate to have had the support of entire families, spanning multiple generations. They were more excited about us winning the Uber Eats award than us. I didn’t know how to thank them, after all, it is they who have won this for us.”

“People don’t just come here to eat,” adds Rathore’s son, Hemendra, who quit an engineering job to join his father. “They come here to meet pitaji (father), and grab a bite while they talk to him. These are relationships built over generations… everyone knows him here. It’s a big responsibility for me to live up to.”

The Rathores claim to have fed many of India’s prominent personalities over the years, including the Adanis, Mittals and Rahul Gandhi. Rathore has never tasted an American hot dog, but says he has many old clients now settled in the US, who always drop by on their home visits. On this day in August, Zurich-based Mayank Dashputre is at JHD, having lunch with his brother. The 26-year-old software engineer has been eating here for as long as he can remember, and says it remains a vital part of his trips back home. “Sometimes, we even eat here twice a day when I’m here,” he says with a grin.

With about 70 percent orders coming from Uber Eats Rathore is now looking at automation[br]The Tech Push

While JHD got requests from multiple aggregators, Hemendra had a friend who worked at Uber Eats, who insisted that they give the platform a shot. “Since he was so keen, we had him speak to our chartered accountant, because I don’t understand these things,” says Rathore. “We thought we would just try it out and see how it goes and got ourselves listed [on the platform] in May 2018.”

Since then, growth has been tremendous. “While we continue to have diners at the outlet, about 70 percent of our business now comes on Uber Eats on some days, it’s even 80 percent,” says Rathore. “I have not earned much in life other than the happy, shining faces of customers. But it is true that since we got on Uber Eats, we have made good money. It doesn’t take much effort from our end, and reaches a wider audience.”

“It really shows the power of technology,” says Raj Beri, head of Uber Eats-APAC. “We often talk about how small and medium businesses are what power Uber Eats, and Johny Hot Dog is a great example.”

For the first time since its inception, Johny Hot Dog is looking to upgrade its operations. For one, it has invested in and is testing out an automation strategy.

“It currently takes about 10 to 12 seconds to serve a customer, but the back-end work that goes into making the tikkis is still cumbersome,” says Hemendra. “They are manually made, so to get them to be consistent is a challenge. We would like to automate that process, and have demoed a machine that can make about 2,000 tikkis in 20 minutes, of a pre-defined size.”“We started small, so we didn’t anticipate these challenges,” adds Rathore, who still works 14 hours a day and does a lot of the cooking himself. “The food industry is only going to become more powerful, and those who adapt to technology quickly will move forward. But for that, we need money.”

The father-son duo claims they have had a few funding proposals, but have declined them all. “I would love to serve my food to the whole country, and I’m confident that the hot dogs would do really well. But I would rather do that with the right partner, maybe as a franchise, and the search is still on,” says Rathore.

In the meantime, JHD is set to open its second outlet, its first milestone in expansion, on the Bhawarkua side of Indore, from where a lot of Uber Eats order requests come.

The menu will remain the same three items, and JHD has no plans to list on other delivery aggregators. The Rathores won’t be physically present at the new stall, but will train a team to manage it, “because otherwise, we won’t be able to open a third stall,” says Hemendra.

“I know we have the potential to take a hold on the country’s fast food market if we find the right partner, because our food will always be fresh and filling, but I don’t want to do too many things at once and disturb the business,” says Rathore. “My passion lies in customer satisfaction, not in money, so I’m always greedy to get to work and meet everyone who comes by. I will be here until my last day.”

â— The writer travelled to Hong Kong at the invitation of Uber Eats

First Published: Aug 30, 2019, 11:55

Subscribe Now