2024: The year of interest rates' climb down

This year most global central banks commenced the long-awaited descent after a slew of rate hikes in 2022 and 2023. But they are turning cautious as they tread a slippery zone of potentially inflation

The current calendar year marked a somewhat weary return to normalcy following a major policy reset to tide over a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic. Nearly five years ago, since March 2020, global central banks slashed rates to historic lows to support their struggling economies.

But the avalanche of unprecedented liquidity created a new monster: Inflation. Faced with the dual problem of anaemic growth and rapidly rising price levels, ‘accommodative’ central bankers dragged their feet to train guns on inflation, and began raising rates from early 2022.

Over the next 18-20 months, to tame inflation and restore macroeconomic stability, most central banks either increased, or held rates. The year 2024 brought some respite for investors and borrowers. But this was much less than what global central banks had signalled and what markets had anticipated.

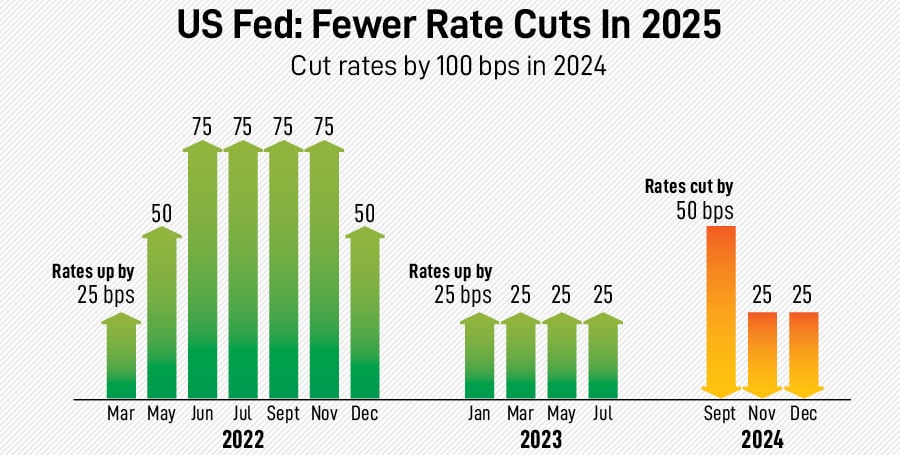

The US Federal Reserve announced three straight rate cuts in the latter half of the year (see table). But on December 18, in the last monetary policy meeting of the year, US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell hit a strongly hawkish note which stung market sentiment and sparked fear across stock markets.

“We have been moving sideways on 12-month inflation," Powell said. “As we think about further cuts, we’re going to be looking for progress on inflation." In fact, the FOMC, is expected to cut rates only twice in 2025, in comparison to its earlier projection of four times in September.

So, it is too soon to declare a victory over inflation. A stronger US dollar, coupled with tariffs and possibility of a crackdown on immigration by President-elect Donald Trump, present a cautious and uncertain outlook for policy easing across global central banks. Fitch Ratings, in its Global Economic Outlook report published in December, projects that the US effective tariff rate could rise to about eight percent from two percent today and stoke inflation, which continues to remain ‘sticky’.

“US inflation risks are rising as consumer spending proves stronger than expected and impending tariff increases are set to push up US import prices," notes Brian Coulton, chief economist, Fitch Ratings. Furthermore, tightening of global financial conditions and volatility in currency markets may force global central banks to walk in tandem.

On December 19, a day after the FOMC meeting, most Asian currencies reeled under the impact of the US Federal Reserve’s projection of fewer rate cuts next year: The Indian rupee tumbled to a record low at 84.94 the Japanese yen hit a one-month low against the US dollar at 155.94 the South Korean yen tanked close to a 15-year low of 1449.9 per dollar.

"We saw US treasury yield rise and dollar index to strengthen post the policy announcement," says Deepak Agrawal, CIO, Debt- Kotak Mahindra AMC. “The Fed policy (announced on December 18) may also limit policy easing by other central banks."

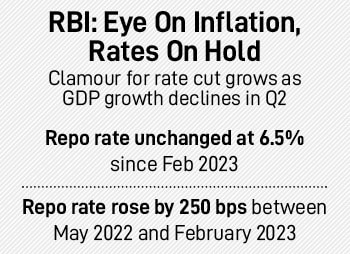

India’s central bank has held the repo rate unchanged at 6.5 percent since February 2023. Former RBI governor Shaktikanta Das, whose term ended on December 10, had reiterated at each monetary policy meeting, the Reserve Bank’s focus on bringing inflation down to 4 percent on a durable basis for sustainable growth. “Our policy is for 1.4 billion people. When inflation comes down, naturally the common man benefits the most," Governor Das stated in the June meeting last year.

In the recently released minutes of the MPC meeting in December, Das said the policy priority at this critical juncture has to be on restoring the inflation-growth balance as the biggest support for higher growth would come from price stability. “The inflation-growth balance has got somewhat unsettled now," he cautioned. “The fundamental requirement now is to bring down inflation and align it with the target."

In the recently released minutes of the MPC meeting in December, Das said the policy priority at this critical juncture has to be on restoring the inflation-growth balance as the biggest support for higher growth would come from price stability. “The inflation-growth balance has got somewhat unsettled now," he cautioned. “The fundamental requirement now is to bring down inflation and align it with the target."

Inflation has been a spot of bother. CPI stood at 5.48 percent in November and 6.21 percent in October. And the Indian economy is growing at a slower clip. In the second quarter of the current fiscal, GDP growth declined to a multi-quarter low of 5.4 percent, much below market estimates. This has increased the clamour for a rate cut. But will the RBI’s rate-setting panel relent?

It is widely believed that Sanjay Malhotra, who assumed office as the twenty-sixth RBI governor on 11 December, will focus on growth over inflation to revive the economy. Most analyst and economists have pencilled a 25bps rate cut in February. But a fragile global macroeconomic environment could force the six-member panel to err on the side of caution.

First Published: Dec 23, 2024, 12:44

Subscribe Now