Earnings to hurt Indian equities, not elections

While poll results could be an excuse for markets to fall, the reasons are more fundamental

Image: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

In an election year, the biggest risk to Indian equities could come not from the outcome of the polls but from a deteriorating macroeconomic environment, rich valuations and a global backdrop that is increasingly vitiated by trade disputes and a return to protectionism.

Indian markets have spent the last four years at valuations that are well above their mean. The benchmark Sensex trades at 24 times (and about 18 times one year forward) earnings pricing in double digit earnings growth, which for the past four years has hovered between 4 percent and 5 percent a year. One reason for this has been the about ₹8,000-12,000 crore per month domestic equity inflows that have left the indices quoting at near their high point even as foreign investors have pulled out and corporate profitability has eroded in mainline sectors like banking and telecom. At 0.8x to GDP, India has among the highest emerging market capitalisation ratios.

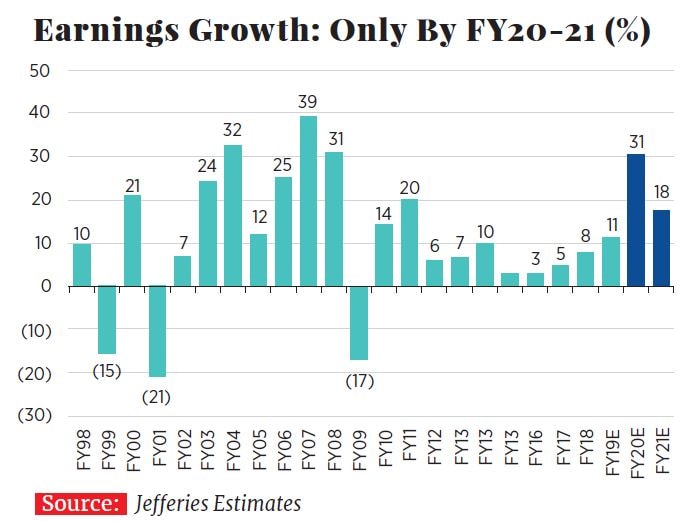

In a recent report, brokerage Jefferies argues that even if profitability recovers, the market could have significant catch up to do. “We see few triggers (for) India’s equity markets this year despite our forecast of 31 percent aggregate EPS growth.” Investors should brace themselves for a messy election outcome that in the short term may impact valuations.Elections have proved to be one-week events for the market. In May 2004, the Sensex fell by 10 percent on each of the two days after the NDA’s defeat but closed the year up by 42 percent on the back of double digit earnings growth. The next four years saw the market quadruple before the Lehman crisis.

The markets rose by 37 percent in May 2009 when UPA-II was elected, but did little in the next four years.

For 2019, the risks are piling up. Consumer spending, which contributes to two-thirds of growth, has reached a temporary bump. With private sector capex still not showing signs of a pick-up and government capex slowing down, it’s not clear where the next drivers of growth will come from. Prospects for a rate cut have dimmed as wholesale price inflation has been inching up. Indian exports are still stuck at the $300 billion ballpark where they were five years ago. Rising imports have led to a higher trade deficit and a weaker rupee, resulting in some skittishness by foreigners over putting in more money. They pulled out ₹100,000 crore in both the equity and debt markets last year. An unwanted election result could see the domestic investor pulling back, giving the markets a long-awaited reason they need to correct.

First Published: Jan 26, 2019, 11:35

Subscribe Now