Gold loans glitter again

With gold prices rising, businesses like Muthoot Finance are poised for a strong run

Someone takes a loan (against gold) when there is a genuine need: George Alexander Muthoot, managing director, Muthoot Finance

Someone takes a loan (against gold) when there is a genuine need: George Alexander Muthoot, managing director, Muthoot Finance

Image: Arjun Suresh for Forbes India[br]Demand at Muthoot Finance, India’s largest gold loan company, surged in July and August. As the country got back to work, small entrepreneurs and traders in need of quick working capital rushed to its 5,330 branches across the country to raise money. The lockdown had seen the value of their holdings rise by a fourth and gold loan financiers were offering loans in under an hour. There were also those who had lost jobs and income and were looking to tide over their immediate expenses.

As the pandemic shut traditional avenues of financing, consumers have moved to monetise their gold holdings. Compare this to the cumbersome process of getting a bank working capital loan and it’s not hard to see why demand for gold loans has surged. “Someone takes a loan (against gold) when there is a genuine need,” says George Alexander Muthoot, managing director at Muthoot Finance, disagreeing that his business has gone up only on account of the rise in prices. Instead, the rise in prices has made his business a lot safer as the value of the security held increased.

Over the last decade there has been a growing acceptance of loans against gold resulting in higher numbers. The increase in gold prices recently hasn’t hurt. Over the last decade the gold loan business has also, like several parts of the financial services business, moved from the unorganised to the organised sector. Where earlier moneylenders would charge upwards of 36 percent for loans against gold, banks and non-banking finance companies now charge between 12 and 26 percent. Organised companies stayed largely under the radar of regulators in the 2000s owing to their small size and the fact that they posed no risk to the financial system.

The rapid rise in gold prices from 2008 to 2013—they rose 170 percent in that period—had resulted in several unscrupulous practices among lenders with instances of companies lending as much as 100 percent of the value of the loan. They were vulnerable to a fall in gold prices. When prices fell in 2013 their loan books soured and the Reserve Bank of India decided to bring them under its supervision. To reduce aggressive lending practices the RBI stipulated that only 75 percent of the value of gold could be given out as a loan. They also have to be adequately capitalised with 15 percent Tier 1 capital.

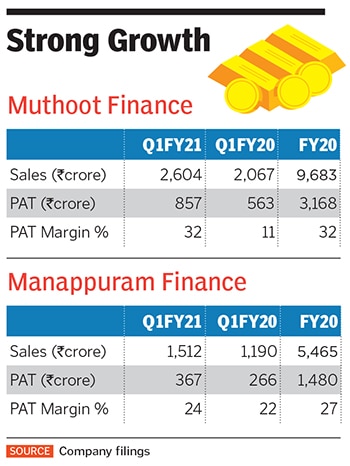

But the additional regulation has not stopped the business from growing. Aiding gold loan companies has been the sentimental attachment Indians have towards gold. Indian households own an estimated 25,000 tons of gold worth ₹130,000 lakh crore, and the government’s attempts to monetise this hoard through sovereign gold bonds have been unsuccessful. Instead they prefer to pledge gold, take a loan, repay the loan and take back their jewellery thereby monetising an otherwise idle asset.The result has been a blowout first quarter performance for Muthoot for this fiscal. Despite most of its branches being shut in April, net profit at ₹857 crore was up 52 percent when compared to the year earlier and 2.6 percent when compared to the March quarter. The company is confident about meeting its 15 percent growth guidance for FY21. The stock has given a return of 23 percent a year since its listing in 2011. Over the last 10 years Muthoot Finance’s sales have grown at a rate of 23 percent a year and profit at 29 percent. Its top and bottom line performance would rank Muthoot among the best in the country across sectors. The reasons are closely tied to the commodity it deals in and its price.

Gold prices and India

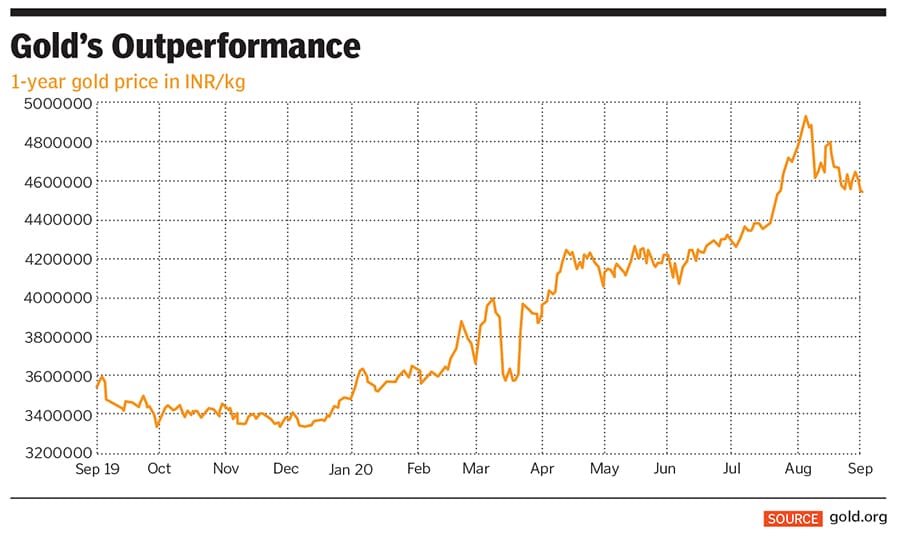

Over the last 40 years the price of gold has moved up 5.93 percent in dollar terms (from about $200 to $2,000 an ounce). But in rupee terms the appreciation has been faster at 8.99 percent. During periods of high inflation bank real interest rates turn negative and Indians view gold as a better store of value. (Another reason is the lack of access to banking for people in smaller towns and rural areas.) More recently, financial products like gold exchange traded funds have tapped into the demand from urban India. For global investors gold has proved to be a good hedge against economic crises and it usually underperforms other asset classes during periods of economic calm. It played an active role after the 2001 dot com collapse and the 2008 financial crisis, rallying 240 percent and 170 percent, respectively. Importantly, it is seen as a leading indicator of equity markets bottoming out and gold started rallying on March 19, a few days before global markets bottomed out on March 24.

For global investors gold has proved to be a good hedge against economic crises and it usually underperforms other asset classes during periods of economic calm. It played an active role after the 2001 dot com collapse and the 2008 financial crisis, rallying 240 percent and 170 percent, respectively. Importantly, it is seen as a leading indicator of equity markets bottoming out and gold started rallying on March 19, a few days before global markets bottomed out on March 24.

According to the World Gold Council, Indian demand fell 1 percent in 2019 to 4355.7 tonnes. A majority of the decline took place in the second half of 2019 as slowing growth began to impact affordability and spending. Demand for jewellery and gold coins and bars was down by 355 tonnes while demand for ETFs rose by 324 tonnes, showing that even before the price rise in 2020 demand had begun to flag. In the first quarter of the current fiscal demand was down 11 percent to 1,015 tonnes.

Past trends have shown that whenever there is a sharp move in prices there is some demand destruction and it takes 3-5 years to catch up. Over a decade demand moves in step with nominal GDP growth. “How long the impairment of demand on account of the crisis continues remains to be seen,” says Vikram Dhawan, head of commodities at Nippon India Mutual Fund, pointing out that the festive and marriage season should be a good indicator of the strength of Indian demand.

If one assumes the present slowdown in global growth will last for another eight quarters, it would be fair to assume that gold prices may still have some way to run. If the Indian government moves to monetise its deficit, the increase in inflation could make gold a better hedge compared to equities or fixed income.

On account of rising prices, two groups of businesses benefit—jewellers and gold loan providers. “Jewellers have their working capital in the form of gold and usually this is not hedged. When prices rise their balance sheet size increases,” says Abhishek Bansal, chairman at ABANS Group, a trading house. There are also inventory gains as gold imported and sold after say a lag of 60-90 days fetches one-time gains. For gold loan financiers it means the value of security increases, allowing them to make larger loans. Well capitalised companies often move quickly to get a slice of this business as their balance sheets allow more leverage. Muthoot accepts only household jewellery as the expectation is that customers have a sentimental attachment to it and will do everything to pay back loans

Muthoot accepts only household jewellery as the expectation is that customers have a sentimental attachment to it and will do everything to pay back loans

Image: Arjun Suresh for Forbes India[br] Muthoot’s Model

At Muthoot rising demand has meant that the company has to be stringent while giving out loans. While 75 percent of the value of gold is permitted it excludes making charges that usually amount to 20 percent of the value. Only household jewellery is accepted as the expectation is that customers have a sentimental attachment and will do everything to pay back loans.

“Even if a customer takes more time to pay we keep a window open and don’t go and auction the gold after the stipulated period,” says Muthoot pointing to the fact that this has helped them win market share over rivals. The company doesn’t do business when gold coins or bars are offered as collateral. The present loan book has an average loan to value of only 55 percent and the average loan size is ₹45,000. In FY 2020 the company wrote off only ₹59.9 crore out of assets under management of ₹40,800 crore.

Aiding organised gold loan companies has been the fact that the cost of borrowing as well as their cost of funds has fallen. This has prompted an increasing number of banks to get into the business. Since these loans are backed by collateral, banks have to keep no risk weights for gold loans.

Muthoot maintained Tier 1 capital adequacy of 25.2 percent in the June quarter and with a gearing of 2.6 times its yields (what it charges borrowers less its cost of capital) are at 21 percent. This led to a spike in its return on assets from 6.3 percent in FY19 to 8.1 percent in FY20. The return on equity was 26 percent in FY20. Muthoot says he is committed to passing on the lower cost of borrowing to his customers and return on assets and equity may not rise much further from here. He is also not keen to borrow more to grow his loan book quicker as that would add to risk even though it would further improve his operational metrics. “I would be comfortable with about a 25 percent return on equity on a sustainable basis,” he says.

For now, Muthoot finds itself well capitalised with demand and acceptance for its product growing at a steady pace. Rising prices also help it in growing its loan book faster. In a sign that the industry is growing rapidly rival Manappuram Finance has also seen its topline grow at 22 percent a year in the last five years.

So what could go wrong and could someone else easily replicate Muthoot’s success? It’s a question the company is often asked. “Operationally the business is very challenging,” says Muthoot. Managing a large network of branches takes its toll. Verifying the purity of gold is a task as is maintaining branch security. The company deals with 200,000 customers a day. A team of 1,000 inspectors is employed to check for fraud and audit the gold kept at its branches. This makes it difficult to scale up beyond the 200 branches the company adds every year and adds a natural moat against competitors.

Lastly, a fall in gold prices would mean that the company may be unable to recover all the interest due to it. But unlike other forms of lending, Muthoot and other gold loan companies will never be in a situation where the principal may be at risk.

First Published: Sep 16, 2020, 12:01

Subscribe Now