Going hammer and clicks

By adapting to online platforms, art auctions are now increasingly reaching bigger audiences and fitting themselves into yet smaller mobile screens

Christie’s live-streaming of the auction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi reached 4.7 lakh people

Christie’s live-streaming of the auction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi reached 4.7 lakh people

Image: Carl Court/ Getty Images

There are things about online art auctions that are anomalous not just to the long-standing, haloed perceptions of art auctions, but also to the new-fangled, whimsical perceptions of online buying.

For one, this is a segment in the realm of serious indulgences. At a time, when even the most established luxury brands remain hesitant and wary of the online world, afraid of losing their jealously guarded exclusivity, online art auctions have gone the whole hog. For another, price tags at these auctions are not anywhere in the realm of popular online buys—usually perceived to be of low value—with purchase values running into millions of dollars.

And yet, the most revered of global auction houses, such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Heritage Auctions, and the crop of newcomers such as India’s Saffronart and AstaGuru have embraced everything that technology has to offer—starting from smartphones and social media platforms, to blockchain and cryptocurrencies—in order to expand their reach, acceptance and credibility.

St Margaret, by Titian was auctioned by Sotheby’s for $2.2 million

Image: Sotheby’s

Online auctions are shaped into two broad formats: Online-only events that are hosted on the websites of auction houses over several days and live, physical auctions in which buyers can bid through an online channel. The latter is similar to the much older concept of bidding over telephone lines, only this new medium frees the buyer from being chained to a telephone line buyers can be based anywhere in the world, and place bids either on the website of the auction house, or through its app.

According to a 2018 Hiscox Online Art Trade Report, online art market sales reached an estimated $4.22 billion in 2017, up by 12 percent from the year before. In the case of Sotheby’s, 23 percent of all lots that they sold in 2017 were purchased by online buyers. Christie’s announced its online sales had risen by 12 percent in 2017 to £56 million. Heritage Auction’s online sales surpassed $815 million in 2017. On home ground, AstaGuru’s total turnover in 2017 was ₹101.9 crore, with art contributing about 90 percent of it.

“Digital has democratised the way people view and buy art,” says Gaurav Bhatia, managing director, Sotheby’s India. “It hardly matters any more if the auction is held in London or New York. You can buy a work that you like from wherever in the world you are with a few clicks. It is really simple.” Sotheby’s has nearly tripled the number of online-only auctions compared to a year ago, adds Bhatia, and continues to see success. “We have an average sell-through rate of 85 percent.”

Dinesh Vazirani, co-founder and CEO of Saffronart, agrees. “In the online model, the pool of people who participate is bigger.” The conventional form of auctions—held at one venue over a few hours—limited the number of participants because they would have to go to the venue, he adds.

In the initial years of going online, different auction houses tried different techniques. “Sotheby’s teamed up with partners, such as eBay, and Invaluable [the world’s leading online marketplace for fine art, antiques and collectibles], with whom it tied up in early 2016,” says Anders Petterson, founder and managing director of ArtTactic, an art market research firm based in London, “while Christie’s has always had its own proprietary online model. It does not partner with anyone, and there is no difference in quality between what it auctions at live events and what it auctions online.” Christie’s hosts 80 to 90 online-only auctions a year. Other auction houses often keep the higher-value pieces—masterpieces by famous artists, or private collections that are expected to draw a lot of attention and bids—for live auctions, while lower-value artworks are auctioned online.

AstaGuru’s online auction of Ganesh Pyne’s The Door, The Windows fetched ₹2.9 crore

Image: Astaguru

And it is not just active bidders who log in to an online auction there are viewers, spread across the globe, who watch the live streaming of auctions, even if they are not bidding on any of the lots. This is borne out by the fact that Christie’s’ live-streaming of the New York event last November, in which Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi was auctioned for $450.3 million, reached more than 4.7 lakh people.

It would, however, be incorrect to assume that all buyers prefer the online route. “There are old-time buyers who still prefer to bid over telephone lines, while the live auction is taking place,” says Sonal Singh, director and specialist head, Christie’s India. “It is a medium they are familiar with, and feel confident about.”

But online, Singh says, is a highly potent platform, not just for sales, but also for awareness and education. “It is an effective medium to draw in a new generation of buyers from a young age,” she says. “Thirty-seven percent of our new buyers came through our online platform.” For instance, Christies.com received 12 million unique visitors in 2017, with visitors coming from 168 countries.

“Sotheby’s social media following, with a combined reach of over 1.3 million followers, is not just the largest of any auction house, but it is also the most engaged,” says Bhatia. “Over 5.5 million people engaged with Sotheby’s social media accounts in 2017. Our major evening auctions are also now streamed live via Facebook.”

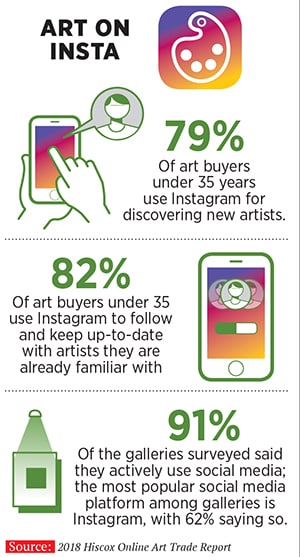

One of the most effective social media tools to emerge in the art auction scene is (not surprisingly, perhaps) Instagram. “Over the last three to four years, Instagram has become a medium to discover new things,” says Petterson. “It is a marketing channel that was not available before. Museums and auction houses are increasingly using social media as a tool. The sheer number of members on Instagram, and its reach, are enormous.”The Hiscox report says the visual platform has become the art world’s favourite social media platform, with 63 percent of survey respondents choosing it as their preferred channel for art-related purposes. “The simplicity and the visual nature of Instagram is ideally suited to the art world, which, combined with its mobile functionality makes it the ideal app for the art world on the move. Although many apps have been created specifically with the art world in mind, the power of Instagram is that it wasn’t,” it says.

But it is still a work in progress.

Even as the numbers look impressive, there are several issues that continue to snap at the heels of online art auctions. The Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2018 says, globally, online art auctions are struggling to convert hesitant and occasional buyers into repeat customers, with price transparency being an important criteria among new buyers—90 percent of new buyers in the report’s survey said it was a key attribute and criteria when buying art online.

Saffronart’s Vazirani agrees that there are two fundamental aspects of the online process—discovery and transparency. The portal provides bidders with all the information that they might want to make a decision about a piece of work. Price, size and provenance comparisons with other artworks by the same artist that have been sold elsewhere are readily available on the website and the app. The information and the time on hand give bidders the opportunity to make more educated decisions, and to consider other lots that are available in the auction. “Our whole auction process has no manual intervention,” he says. “We publish the results of our online auctions immediately, and there is no scope to make any sale after the auction has officially closed.”

[qt]“The future is about convergence. And it is all converging on the smartphone.” - Dinesh Vazirani, Co-founder and CEO, Saffronart[/qt]Loyalty among buyers is another niggling issue: The Hiscox report says that 81 percent of buyers purchased art from more than one platform, with 53 percent of the big spenders buying from three or more platforms.

Image: Christie's

Petterson of ArtTactic says the new online auction houses often face the problem of logistics. “Selling the artwork is just one part of the process. Delivering artworks undamaged and on time is another,” he says. “Old auction houses have long-standing relations with logistics companies, and it is easier for them to transport the artwork, whereas new auction houses struggle with it. This often adds up to a poor customer experience.” Long, trustworthy relationships are also what procurement of artworks is based upon. “A family that has important artworks with them may feel more comfortable working with a legacy auction house, rather than something new because they are not sure of what the experience is going to be like,” adds Petterson. This is further exacerbated by the increase in the number of auction houses, platforms and mediums, and the rising competition among them to procure artworks. “There is not, after all, an infinite supply of art work.”

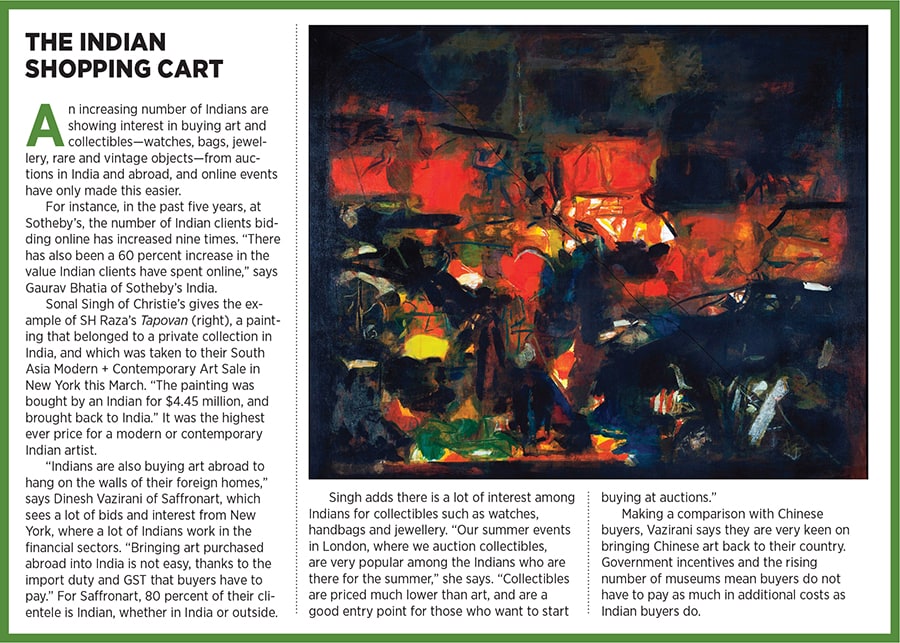

Anju Dodiya’s The Site were auctioned by Saffronart for record prices

Image: Saffronart

Highlighting this aspect is Tushar Sethi, CEO of AstaGuru, which started online auctions in 2008. “Paintings are becoming rarer to find. One of the reasons is the building of museums by business families in India.” These museums, he says, need important pieces of artworks, and the demand from them is going up. However, once bought by one of these museums, that particular artwork is unlikely to come back into the market for a long time. “They will disappear from the market.”

Keeping this in mind, AstaGuru holds only two online auctions a year. “We don’t want to increase the number of auctions we host,” explains Sethi. “Instead we want to hold a few auctions, but with pieces that are of exceptional quality. We have created 22 record prices for artists.”

In its 2017 August-September auction, AstaGuru sold a Ganesh Pyne painting The Door, The Windows for ₹2.9 crore it was bought by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. “Pyne’s older brother meant everything to him. When he died, Pyne painted The Door, The Windows, and it marked a watershed in his painting style, after which his works became dark and brooding. The significance of this painting is immense,” says Sethi. He adds that it took four to five years to convince the owner of the painting to put in on sale.

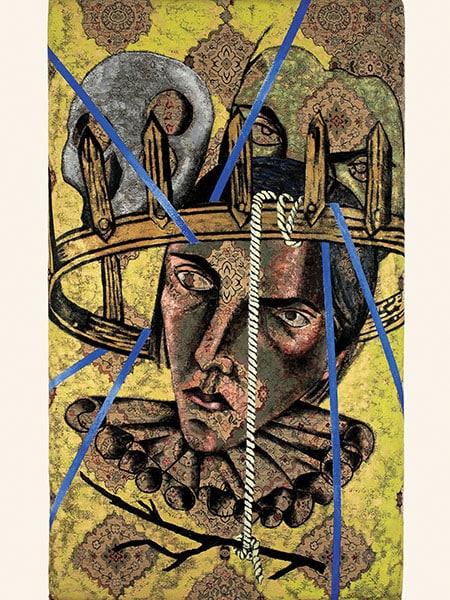

Mahadev Visvanath Dhurandhar’s Tarabai-Founder of the Kolhapur Confederacy were auctioned by Saffronart for record prices

Image: Saffronart

Unlike most non-luxury ecommerce platforms, which remain exclusively online, art auctions are moving towards a hybrid model that includes live auctions as well as online events. So, while legacy auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s now have a strong online presence, those who started out as online-only auction houses now have live events. The Hiscox report predicts, “With online art platforms dependent on quality inventory, and the traditional art businesses in need of a strong online presence, we are likely to see increasing convergence between online-only businesses and traditional art businesses in the coming years.”

Vazirani of Saffronart, which started live auctions in 2013, agrees. “The future is all about convergence,” he says. “And it is all converging on this,” he adds, holding up his smartphone. “As the lives of more and more people go online, they don’t go out as much as they used to. And rich people are nervous about sitting in live auctions.” The smartphone is what seems to have changed the way the world views and buys art. The Hiscox report found that the use of mobile phones has increased significantly, rising to 20 percent in 2018 (up from 4 percent in 2015). This is in line with the near-doubling of mobile web traffic from 2014 to 2018.

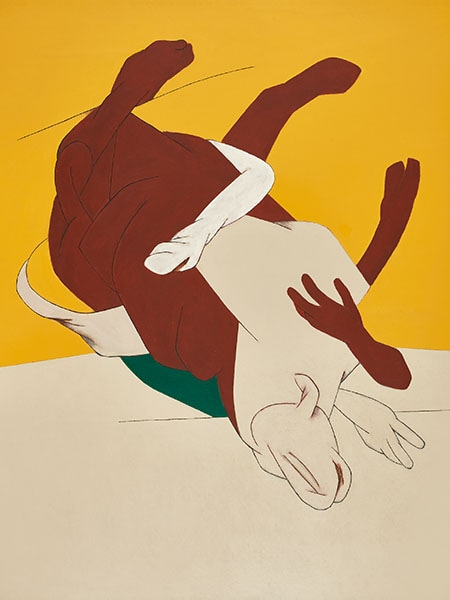

Tyeb Mehta’s Bull was auctioned by AstaGuru for ₹19.98 crore

Image: AstaGuru

Art auctions have always been an arena of drama, with the pantomime-like act of the auctioneer who drums up excitement as well as prices. The hushed excitement that the entry of a famous piece creates in the audience, the one-upmanship among bidders vying to acquire a covetable work, the gasps at the astronomical levels the prices inch towards, and the final knock of the auctioneer’s hammer as he proclaims “Sold!” are just some of the elements of the performance. But as everything else in life slips behind lit screens of varying size, so does this. But when everyone stands to gain, who’s really complaining?

First Published: Jul 21, 2018, 08:06

Subscribe Now