In Search of the Elusive Jaguar

Chasing the jaguar, the Americas' tiger, in the Brazilian Pantanal

Wildlife tourism is heavily focussed on large predators. Perhaps like Ernest Hemingway, wildlife tourists want to wrestle these ferocious creatures bare-handed, although most seem to prefer safer vantage points.

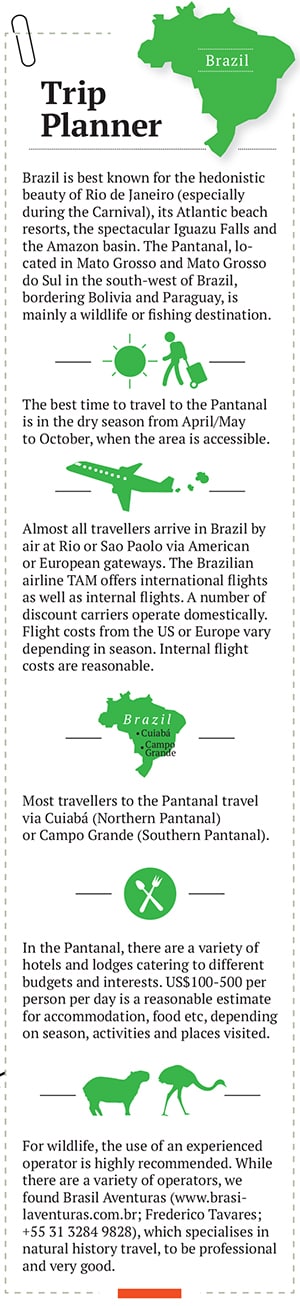

If you’re rolling your eyes and thinking “Indian tourists!”, rest assured that this is not only a subcontinental phenomenon. In the Americas, the place of the tiger is occupied by the jaguar (panthera onca), the apex predator, surpassed in size only by lions and tigers. The best and most reliable place to see jaguars is Brazil’s Pantanal.

The Pantanal (from the Portuguese pântano, swamp or marsh) is one of the largest wetland areas in the world, covering up to 195,000 sq km, mostly in Brazil. Largely submerged during the rains, it consists of distinct eco-systems that support a rich array of plant life and wildlife species.

However, the Pantanal is not a pristine wilderness it includes agricultural properties, primarily raising cattle. Assisted by money from NGOs and donors (expiating the guilt of having destroyed nature in their homelands), many farms now engage in tourism—sometimes their main activity—and support conservation.

Third Time Lucky

On our first visit to South America almost 15 years ago, we found the pristine rainforests of Peru and Ecuador beautiful and frustrating in equal measure. Hallmark mammal and bird species were difficult to spot in the thick and dark forests. We recorded many ‘heards’, not as many ‘seens’. Although the areas we visited were known to be home to jaguars, we never saw any. We got tired of the familiar refrain, “If you had only been here last week…”

Rachel, our guide in Ecuador, advised us that many of the species are more easily and better seen in the wetlands bordering the Amazon basin. We travelled subsequently to Venezuela’s Llanos, the northern equivalent of the Pantanal, and Central American rainforests in Costa Rica. But the jaguar eluded us.

The closest we came to encountering the predator was in Venezuela. At Hato Piñero, we went out before dawn. We didn’t see a jaguar, though we did glimpse the rotund, sizeable rear of a startled tapir retreating into the forest.

On the way back, Otto, our guide, checked the dirt road. There it was—fresh, full-sized jaguar paw prints right on top of our tyre tracks. The cat had walked by after we had driven past. But try as we might, we never found the jaguar.

On our third trip to South

America, we are optimistic. The Pantanal is home to one of the largest jaguar populations—and also 300 mammals, 1,000 species of birds, 480 reptiles, 50 amphibians and 325 varieties of fish.

Carrying the Dead

We plan to spend two weeks in the northern Pantanal in August/September, towards the end of the dry season, to maximise our wildlife-sighting opportunities. But our first target is something rarer than a jaguar.

Serra das Araras, a few hours’ drive from the city of Cuiabá, is billed as an ecological reserve. Though severely degraded by mining and cattle ranching—there are only remnants of the original spectacular plateaus, forests and savannah—the cattle farm is the nesting site of a pair of Harpy Eagles. Named after the Harpies, the winged spirits of Greek mythology that carried the dead to Hades, an adult Harpy Eagle’s wing span is more than two metres. The larger females weigh up to 9 kg, while the males are around 6 kg. Only the Philippines eagle and Steller’s sea eagles are larger.

The Harpy Eagle’s large talons and power allow it to catch and kill large prey, traditionally monkeys and sloths picked up from the upper canopies of tropical lowland rainforests. Threatened by loss of habitat because of logging, agriculture and mining, and also hunted by farmers seeking to preserve livestock, they have been wiped out in many parts of South and Central America.

So it is a matter of much excitement that the Harpy Eagles are known to be nesting in the reserve: They do not breed every year but, this year, they have a chick. But the chick has already fledged and the nest—made from twigs, sticks and branches, several metres across and very deep, 30 metres above the ground in a Cambará tree—is empty. We wait.

Around dusk, a large bird flies into a tree near the nest. The pale chick is unmistakeable by appearance and size. The parents do not appear.

Next morning, we spot the chick near the nest but there is no sign of the adults. In the late afternoon, some newly arrived British bird-watchers locate an adult. We watch the huge female through a telescope. Falling darkness forces us to leave. The lingering British birders see the male returning to the nest with the carcass of an armadillo for the chick. We kick ourselves for not having stayed longer.

The next morning, we make one last hopeful trip to the nest. Again, the chick is there but the adults are missing. After a couple of hours, I notice a Plumbeous Kite, a smaller grey black raptor, suddenly take off. The female Harpy Eagle has landed in a dead tree only metres from us.

In the morning light, every feature of the bird is visible: the slate blue-black upper feathers, the white belly, the broad black band across its breast, the pale grey head, the extraordinary double crest and even its grey-brown eyes. The yellow talons—at 15 cm, longer than a grizzly bear’s—are unmistakeable. The Harpy Eagle sits there for more than 30 minutes, offering us an extraordinary view. Then, in response to a call from its chick, it flies to the nest, revealing its massive wing span.

An Easy Profusion

After the diversion, we travel south along 150 km of the Transpantaneira Highway to the Cuiabá river. Road construction has left large depressions on either side of the highway, which become a source of water during the dry season, attracting birds and animals. It provides abundant “drive-by” wildlife-spotting opportunities.

Earlier, the highway was frequently blocked by cattle. Today, the congestion comes from mini-buses and cars ferrying tourists from all over the world, reflecting the evolution of wildlife watching into a pastime as wealth, leisure and conspicuous consumption increase.

There are numerous pousadas (inns) and eco-lodges. We stay at a number of lodges to experience different habitats: Grasslands, gallery forests and waterways. Our days fall into a pattern: Pre-dawn drive, post-breakfast walk or drive and late-afternoon excursion extending into the evening as well as the occasional post-dinner outing.

Wildlife is concentrated around available water. Our excursions provide excellent sightings of primates (black howlers, black-striped tufted capuchin monkeys and marmosets) as well as marsh deer, brocket deer, peccaries and agoutis. Every water hole is filled with Yacare caiman. Capybaras, the world’s largest rodents, are everywhere. Night drives reveal tapirs, crab-eating foxes, raccoons and southern tamanduas, an anteater.

After our Venezuelan sighting of a tapir’s rear, we get good views of the animal. The largest land animal in the Americas combines the features of a horse, a rhinoceros and a hippopotamus. We see two mothers with young. We watch a male crossing a stream totally submerged, walking along the bottom.

We record more than 250 species of birds, including several ‘lifers’—birds seen for the first time. There are the ostrich-like rheas and partridge-like tinamous, a profusion of water birds including a variety of herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, cormorants, darters, screamers, wildfowl, rails, jacanas, kingfishers, sun bitterns, swimmers and storks, such as the giant jabiru. Birds of prey, such as ospreys, snail kites, crane hawks, black-collared hawks, great black hawks, savannah hawks and roadside hawks, as well as falcons and vultures, are everywhere. There are numerous arboreal pheasants such as guans, curassows and chachalacas. We spot hyacinth macaws, the largest parrot in the world, distinctive in their cobalt blue plumage, blue and yellow macaws, various parakeets and toucans. There are bewildering varieties of pigeons, doves, cuckoos, tanagers, jays, swallows, manakins, hummingbirds, trogons, motmots, puff birds, jacamars, woodpeckers, woodcreepers, antbirds, shrikes, tyrants and flycatchers as well as owls, nightjars and potoos.

Given the ease with which all these species can be spotted, people with hitherto little interest in nature are reborn as instant experts, becoming, like Woody Allen, at “two with nature”.

But the jaguar is still elusive. On a drive between two lodges, a brownish feline shape crosses the road about a kilometre ahead. By the time we reach the spot, the only evidence of the jaguar is the alarm calls of birds and monkeys.

The Cuiabá river, east of Porto Jofre, is reputedly the best place in the world to see jaguars. The ban on hunting and decades of motorboat fishing has habituated the jaguars to human presence. We have four full days at Porto Jofre.

Tourists go out all day or on separate dawn and late afternoon excursions. Large organised groups use big powerful motor boats, while smaller groups or independent travellers use motorised canoes. They search for jaguars along the Cuiabá or its branches, the Piquiri or the Three Brothers rivers.

The jaguar has to be on the riverbank. If the cat retreats into the thick jungle lining the river, it is invisible. Once one is spotted, the boat broadcasts its location by two-way radio, allowing other boats to share the experience.

On the first day, we see giant river otters, a rare neotropical otter as well myriad birds and bats. We see a magnificent king vulture, the largest New World vulture other than the Condor. Every feature is clearly visible, as the bird is perched a few feet from the boat. It is predominantly grey and white but its head and neck are yellow, orange, blue, purple and red. There is an irregular golden crest above its orange and black bill.

That evening we discover that everyone else has seen a jaguar or two. Feigning patient equanimity and polite disinterest, we smile whilst contemplating mass murder.

It confirms English nature journalist Bill Oddie’s observation about bird and wildlife watchers: “Tense, competitive, selfish, shifty, dishonest, distrusting, boorish, arrogant, pedantic, unsentimental and, above all, envious”.

Our luck turns the second day. A jaguar is sighted on the Piquiri. It will take us about 45 minutes in our canoe to get there, by which time the jaguar may have moved on. We try another part of the river. A fisherman tells us that he has seen a jaguar on a sand bank a few hundred metres away.

We spot the jaguar swimming across the river. Its basketball-size head is only a few metres from us. It is a big male, nicknamed Borboleta (Portuguese for butterfly), after the distinctive pattern on his forehead.

The jaguar is more than 1.8 m from nose to tail and probably about 75 cm at the shoulder. It is a tawny yellow, covered in rosettes for camouflage in the dappled light of the forest. Borboleta must weigh over 100 kg. It is bigger and stockier, with shorter, thicker legs than leopards we have seen elsewhere, adapting it perfectly to hunting its preferred prey: Capybaras, peccaries, tapirs or fish.

The jaguar rests on the side of the river, close to our boat. Within minutes, about 20 boats arrive, jostling for position to provide its occupants and their several hundred thousand dollars’ worth of photographic equipment with the ‘money shot’.

Eventually, irritated by insects, Borboleta continues its patrol. We follow until it turns into the forest, out of sight.

Having seen the object of our journey, we take a day off from jaguar chasing to the bemusement of our fellow travellers, who cannot conceive of anything other than more cats. We travel four hours up the Piquiri to see a yellow armadillo as well as several families of giant river otters.

Over the remainder of our time in Porto Jofre, we see jaguars on five separate occasions. In total, we see five individuals, including Borboleta twice and a female three times near the lodge itself.  The Crucifixion of Nature

The Crucifixion of Nature

The diversity and beauty of the Pantanal is breathtaking. But we are disturbed by the degraded environment and industrial wildlife tourism. Nature barely survives, preserved only, it seems, for exploitation. The abject poverty of the local people, the Pantaneiros, suggests that the bounty does not trickle down very far.

The Harpy Eagle nest site lies in a tiny patch of forest cleared areas on all sides of the towering tree, providing birders and photographers with better viewing opportunities. The farm has a small population of sheep. As it is not a traditional activity, the suspicion is that they provide food for the eagles, compensating for a lack of natural prey in the vicinity. It ensures that the eagles return, supporting the lucrative commerce. Pantanal property owners now run cattle almost as bait for jaguars to ensure good sightings for wildlife tourists.

The guides know of no more than 50 jaguars in the area, too small a genetic pool for a sustainable healthy population. If the numbers grow, then the need for additional territory will bring them into conflict with humans.

We saw our first hyacinth macaw on the Transpantaneira Highway. It was a single aged bird, which has probably lost its mate. The macaw perched on an electrical pole. We and another group of tourists stopped, in their case to take photos. The large bird overbalanced on its perch and desperately grabbed the live wires, electrocuting itself. It did not die instantly, shrieking in agony and terror before falling to the ground.

We were distraught. The other tourists got out of the car, walking to the body to take more photos and collect the gloriously colourful feathers.

Along with the many beautiful images of the creatures of the Pantanal, this memory haunts us. Genesis in the Bible speaks of God giving man dominion over “every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. Irrespective of faith, it is a responsibility that the human race does not discharge well.

Satyajit Das is a former banker and author of Traders Guns & Money and Extreme Money

First Published: Jul 10, 2013, 05:36

Subscribe Now