Will the govt's agri reforms seed change for farmers?

The reforms aim to open up a nationwide market for farmers. But that's a far way off without supporting infrastructure and storage facilities

Sambhaji Jaid at his farm in Manchar, Mahrashtra

Sambhaji Jaid at his farm in Manchar, Mahrashtra

Courtsey: Farmpal For years, Dnyandev Hon travelled 20 km with his produce in a rented vehicle, twice a month, to the Kopergoan Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandi in Maharashtra. On some days, he even travelled about 200 km when he needed to sell his produce—onions, wheat or soyabean grown on his 1.5 hectare farm—at the Pune APMC mandi.

“The involvement of middlemen didn’t allow us to get a fair price for our produce. It was painful to see that all our hard work and sacrifices had no value, with the middlemen pocketing 50 to 60 percent,” recalls the farmer, adding that sometimes they were unable to recover even the transportation costs.

One thing was clear to him—he had to educate his three children enough so they didn’t have to go through what he did. He remembers telling his children, “Work hard, and become anything in life, even if it’s a clerk or a peon at a bank, but don’t become a farmer.”

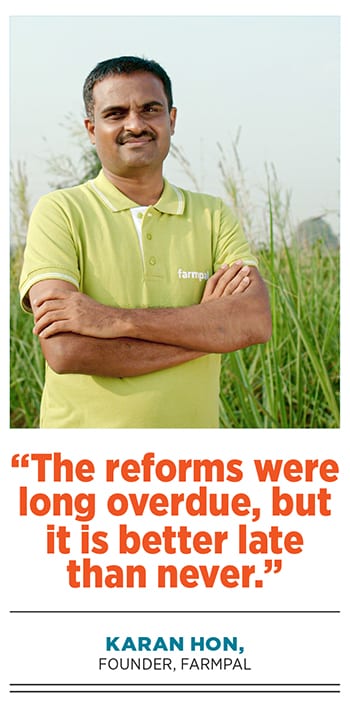

Karan, Dnyandev Hon’s son, became an engineer, went and worked with tech giants like Tech Mahindra in Denmark and SAP in Australia, then returned to India. In 2017, he set up Farmpal, a farm-to-market company, to ensure other farmers did not have to suffer like his father. The company lets farmers know the price of their produce before they harvest the crop, pays them a premium of 15 to 30 percent over what they would get in a mandi, collects the produce from them, processes it and sells it to retailers and hypermarkets.

“At the local mandi, we had to sell at whatever price the local trader offered,” says Sambhaji Jaid, a farmer from Manchar, about 60 km from Pune, who jumped at the opportunity when Farmpal reached out to him three years ago.But farmers like Jaid and startups like Farmpal were still restricted to selling and buying in particular states, due to the stringent rules and regulations. Now, with the new agriculture reforms announced in June, Farmpal is looking at nationwide expansion and Jaid will have far more options.

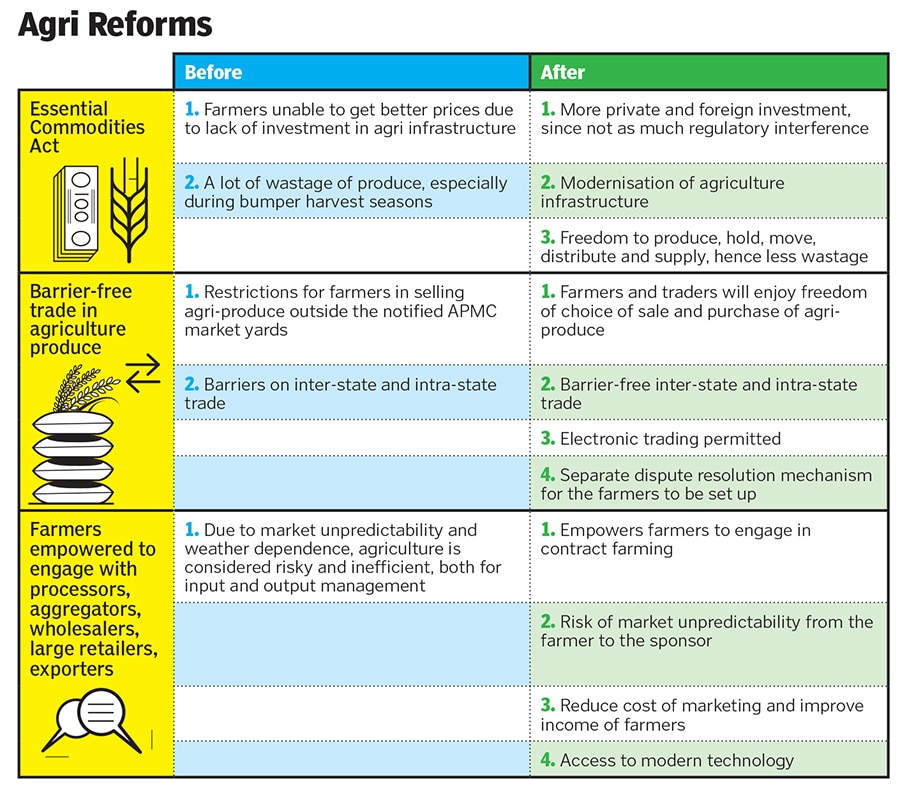

The reforms announced were three-pronged: First, an amendment to the stringent 65-year-old Essential Commodities Act (ECA), removing cereals, edible oil, oil seeds, pulses, onions and potato from the list of essential commodities. “The freedom to produce, hold, move, distribute and supply will lead to harnessing of economies of scale and attract private sector/foreign direct investment into agriculture sector,” said the press release. Secondly, farmers and traders will enjoy freedom of choice relating to sale and purchase of farmers’ produce with the barriers to inter-state and intra-state trade removed, a farmer can also do e-trading of agricultural produce. Thirdly, an ordinance has been passed to allow contract farming, which lets farmers make contract arrangements with retailers, exporters and processors.

In 2017, when he was setting up Farmpal along with his co-founder Puneet Sethi, Karan recollects, “We had to go through a number of obstacles to get a licence to operate in Maharashtra.” Besides, the access of agritech players like Farmpal was restricted to farmers in a certain geography, as each state had its own licence, underlying processes, paperwork and costs. “These reforms were long overdue, but it is better late than never,” says Karan, adding that the three-year-old startup can now expand rapidly across the country.

“Since there is no stock limit on essential commodities now, we can choose to store our produce in a cold storage, if prices have crashed,” explains Jaid, who gets his payment via direct bank transfer within three to four days of sale. He adds, “We now have the choice to sell to whoever gives us the best price, not just within the state but in other states too.”  APMC mandis, like the one in Azadpur near Delhi, will have to rethink their role by providing improved linkages between farmers and organised clients

APMC mandis, like the one in Azadpur near Delhi, will have to rethink their role by providing improved linkages between farmers and organised clients

Image: Sanchit Khanna/Hindustan Times via Getty ImagesWith a push from the government for e-trade of agriculture produce, Mumbai-based startup AgriBazaar too sees a lot of potential for growth. The startup has replicated the physical mandi to an e-mandi aggregator model, where once a farmer registers and uploads his produce, buyers can place orders for purchase.

“Why does a farmer go to an APMC mandi? To sell his produce, get a fair price via auctions, and logistical support," says Amit Agarwal, CEO and co-founder, AgriBazaar. "Through our platform, we are enabling each of these functions. Right from an option between negotiable trade and fixed auction to transferring funds via our digital wallets and facilitating logistics.” Currently, the startup is working with over 2 lakh farmers in 21 states. However, as with Farmpal, AgriBazaar’s licences limit it to trading in individual states.

AgriBazaar is like a private counterpart to the pan-India electronic National Agriculture Market or eNAM platform, except that eNAM does not help facilitate logistics. Now, with these reforms in place, Agarwal says eNAM might be open to tie-ups with private players like AgriBazaar.

The Mandi Conundrum

APMC is a marketing board established by each state government, under which as per earlier rules farmers had to make the first sale of their produce at APMC’s market yards or mandis. The objective was to ensure farmers get fair prices and are safeguarded from exploitation by large retailers. “There are inspectors in the yards to ensure traders do not cheat our farmers,” says PS Gajera, secretary of the APMC in Junagadh, Gujarat. He agrees that the reforms are likely to benefit farmers, but “even with the market open, I feel farmers will benefit the most if they come to the market yard,” he adds.

Private and foreign investment coming into the market will also bring in more competition in the form of private mandis, so APMCs will have to focus on improvements to ensure farmers continue trading via the yard, says Gajera. APMC yards usually provide facilities like waterproof platforms to store produce, and facilities for farmers to sleep and eat.

With farmers under no compulsion to sell at APMC mandis, the food supply chain is likely to evolve, and these mandis might need to rethink their role in providing improved linkages between farmers and customers, since the economics work out better that way. “APMC mandis can play a facilitative and value-added role in connecting farmers to organised players as well as e-markets like eNAM,” says Arindam Guha, partner, leader-government and public services, Deloitte India.

Hemendra Mathur, venture partner at Bharat Innovation Fund, an early-stage venture fund that invests in agri innovation startups (among other sectors), adds that there will be a co-existence of multiple supply chains. “There will be more de-layering and disintermediation in the supply chain, allowing for a more direct connect between farmers and customers,” he says.

But APMC mandis are unlikely to be substituted entirely as they are an important medium for price discovery. Besides, though it has been argued that farmers might obtain a higher price by selling to buyers of their choice, R Ramakumar, Nabard chair professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, believes there is no evidence that amending the APMC Act will, by itself, improve the price realisation of farmers. In fact, he says, “The absence of APMC markets may lead to a huge void in the agricultural marketing sector, which might open up the field for acute exploitation and harassment of farmers.”

According to him, procurement should be expanded, larger public investments should flow into creating modern farm storage structures, and these storage systems should be efficiently aligned with the expansion of the public distribution system. “The government does not want to invest in farm storage, but leave the sector open to investment by private players. The ECA is being amended since it is believed to be the reason why no private investment is flowing into warehousing and storage spheres. However, he points out, that Kerala had no APMC Act and Bihar nullified its APMC Act in 2006. “But in neither of the two were there any major inflow of fresh investments from the private sector,” he says.

The Way Forward

While the reforms look good on paper, they won’t translate into benefits unless accompanied by investments in infrastructure, logistical support and cold storage facilities. Jiyalal Chauhan, who moved from Delhi to Dehradun in Uttarakhand to do organic farming in 1996, used to sell in APMC mandis when he started out, but stopped after he saw the exploitation taking place. Currently, he only supplies to his customers via home deliveries. “We used to sell at the weekend organic food mandis in Dehradun, but stopped doing that since farmers would sell regular produce as organic and our customers started losing trust in us.” But farmgate collection remains uneconomical. “There is a need for smaller collection centres near villages that could be set up by large corporates,” says Mathur. Foodgrains in India are usually stored in archaic warehouses and open plinths without any use of technology. According to Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates, nearly 40 percent of the food produced in India is lost or wasted.

But farmgate collection remains uneconomical. “There is a need for smaller collection centres near villages that could be set up by large corporates,” says Mathur. Foodgrains in India are usually stored in archaic warehouses and open plinths without any use of technology. According to Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates, nearly 40 percent of the food produced in India is lost or wasted.

With the opening up of intra-state selling, Jiyalal is also confident he can harvest a lot more produce and sell to other states, but he doubts the logistical support from private firms will reach small farmers like him.

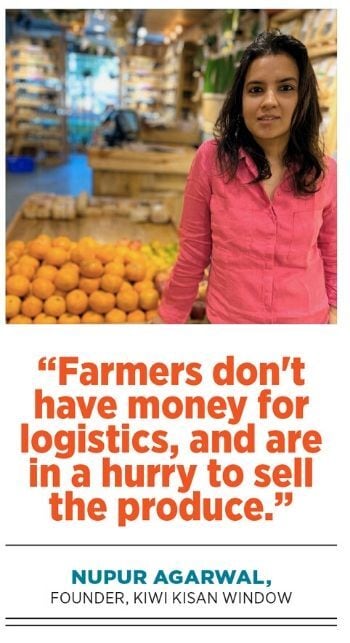

“The reality is that an Indian farmer does not have enough money to pay for logistics and as the product is highly perishable, he is always in a hurry to sell his produce as soon as possible,” explains Nupur Agarwal, founder of Kiwi Kisan Window (KKW), which works with farmers like Jiyalal directly to generate employment by procuring fruits, vegetables and grains from them. In her opinion, these reforms never end up reaching the grassroots.

The current need is to improve sustainable storage facilities. Private sector companies like Adani Agri Logistics for instance, have been a pioneer in bulk handling, storage, and transportation by creating silo capacities nationwide, wherein the loss of grains is negligible. Adani Agri Logistics has created a silo capacity of 8,75,000 tonnes across Punjab, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh.

Agarwal of AgriBazaar adds that for farmers to sell goods to other states, there needs to be a strong network of cold-storage facilities as well, which is currently inadequate. There are very few private cold-storage facilities in Uttarakhand, and the few times Jiyalal has paid the hefty rent to use them, he has been cheated. “They exchange our good quality potatoes with their bad quality produce. I have no trust in them,” he says.

“Currently there are only large cold-storage facilities what we need are smaller facilities near villages,” says Mathur of Bharat Innovation Fund. Besides, there is also a need for a digital platform that can enable the collection and dissemination of information on the pricing and produce across mandis in real-time, he adds. The reforms, he says, are also an opportunity to use technology like satellite mapping for national-level planning, including deciding the location of warehouse or cold-storage facilities.

From Dnyandev Hon to Sambhaji Jaid, things in the agriculture sector have changed, but at a slow pace. The hope is these reforms will give a boost to the sector in the right direction.

First Published: Jun 16, 2020, 12:18

Subscribe Now