Carbon Masters: Fuelling new possibilities

Carbon Masters, with its asset-light model, is powering Mahindra & Mahindra's biogas plant

Som Narayan expects Carbon Masters’ Malur plant to run to its full capacity of 1,600 kg by March 2018

Som Narayan expects Carbon Masters’ Malur plant to run to its full capacity of 1,600 kg by March 2018

Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

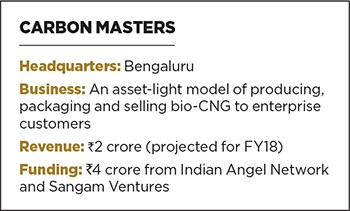

In April 2016, when Som Narayan, 32, and Kevin Houston, 65, agreed on a deal with Mahindra & Mahindra, it was the kind of association they had dreamt of.

After being in the business of advising clients on reducing their carbon footprint and then producing bottled bio-CNG (a purified form of biogas) over the past eight years, they would be running a biogas facility at Malur, a town about 50 km from Bengaluru, for Mahindra Powerol, a generator manufacturing arm of the $15-billion Mahindra & Mahindra Group, for eight years. While Mahindra would spend about ₹7 crore on installing the facility, Narayan’s and Houston’s venture, Carbon Masters, would procure wet waste for producing biogas and organic fertilisers, and package and sell the gas. The plant, with a daily production capacity of 1,600 kg, was about eight times as big as their existing facility at Doddaballapura in Karnataka.

Mahindra, on the other hand, was impressed with Carbon Masters’ focus on “sustainability”. “The Malur bio-CNG project is Mahindra’s first commercial waste-to-energy project, which not only generates green energy but also creates rural employment and supports the farmer community with the organic fertiliser. This very well synergises and supplements Mahindra’s vision of farm tech prosperity,” says Hemant Sikka, president–chief purchase officer, Powerol & Spares Business, Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd.But even as Houston and Narayan signed on the dotted line, they knew that a rocky road lay ahead. The company needed to make some investments to run the plant, and despite Houston, a former executive at Procter & Gamble, and PwC already having invested ₹50 lakh of his personal money, more was required.

Consequently, they spent much of 2015 scouting for funds. “We just did not know how to raise funds,” recalls Houston, while we sit at Konark restaurant in Bengaluru, one of Carbon Masters’ early clients for the bottled biogas. “The best that we could get was some consultant who would promise to raise the money from banks against a cut,” says Narayan. “We signed the deal in May 2016. Until then, we had done everything from understanding the space and building a team to running pilots. This plant was one box on the checklist that we had to tick off.”

But fresh funds remained elusive, while the plant at Malur was nearing completion. It was not before another year that Houston and Narayan could finally breathe easy.

Help came from an unlikely quarter. Konda Vishweshwar Reddy, a Member of Parliament from Telangana, whom Narayan had met at multiple conferences, introduced the duo to the Indian Angel Network (IAN). Soon, they found patrons in angel investors Nagaraja Prakasam and Mridula Ramesh, and Sangam Ventures, a sustainable energy-focussed fund backed by the Shell Foundation. In June 2017, IAN and Sangam Ventures invested ₹4 crore in Carbon Masters, a crore more than the company’s initial ask.

Today, Carbon Masters processes about 35 tonnes of wet waste, sourced from multiple waste procurement firms in Bengaluru, including Saahas and Hasirudala, and garbage contractors recognised by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagar Palike (BBMP), to produce about 1,000 kg of bio-CNG and 10 tonnes of organic fertiliser every day at the Malur plant. Narayan expects the plant to run to its full capacity of 1,600 kg by March 2018. A few more plants are expected to come up next fiscal, he adds.

Apart from this, Carbon Masters has developed an engineering unit in Bengaluru that will handle conceptualisation, commission and operations of biogas plants. The results so far have encouraged Narayan and Houston to aim for about ₹30 crore in annual revenue in the next three years, compared to the current revenue run rate of ₹2 crore.

“What excites me is that Carbon Masters is able to package and sell [the gas]. It helps customers because they don’t need to switch between LPG and biogas, and lose efficiency in the process. It is a win-win for waste management companies because earlier, they used to compost the waste, which would take months. Now, they can just hand over the wet waste to Carbon Masters,” says Prakasam. “India produces 1.5 lakh tonnes of waste every day, and half of that is wet waste.”

With every development, Houston and Narayan are moving a step closer to their dream of reducing carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere.

An April 2017 report by the United States Environmental Protection Agency states that carbon dioxide accounts for 82 percent of the total greenhouse gases, when compared to methane’s 10 percent. Methane, however, absorbs 100 times more heat than carbon dioxide over five years, and 72 times over 20 years. Though methane breaks down faster than carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, its capacity to retain more heat makes it more dangerous.

“The best one to tackle first is methane because it has a higher global warming potential,” says Narayan. “When you burn methane from a biogas plant, it gets converted to carbon dioxide [and moisture], but this is biogenic. But, when you take coal and burn, it is incremental carbon dioxide being released in the atmosphere.” This explains Carbon Masters’ biogas product, CarbonLites, which is 92 percent methane. Narayan and his University of Edinburgh colleague Kevin Houston set up Carbon Masters with an office on the university campus in 2009

Narayan and his University of Edinburgh colleague Kevin Houston set up Carbon Masters with an office on the university campus in 2009

Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

It wasn’t a smooth start for us, says Houston, who started pondering over global warming after watching An Inconvenient Truth, a 2006 documentary by Davis Guggenheim featuring former US Vice President Al Gore. All hell broke loose when he decided to quit his consulting job at IBM in the UK to go back to school to study carbon management at the age of 55. “At the time, my three adult children were leaving university. They felt I was crazy, having a midlife crisis and had lost the plot,” he jokes.

Houston met Narayan at the University of Edinburgh in September 2008, where both were studying for their master’s in carbon management. The two set up Carbon Masters, with an office on the university campus and four other employees, in May 2009, while still at university—with a 10,000-pound interest-free loan from the university’s incubator—to advise businesses on ways to reduce their carbon footprint. Over the next two years, Carbon Masters wangled projects from the European Commission in Brussels, the Edinburgh airport, drug manufacturer Pfizer and steel manufacturer Adelca Edinburgh University, in fact, was their first client. The company clocked about ₹20 lakh in annual revenues in FY13.

Towards the end of 2011, Narayan had to return to India. His visa had expired. “We thought it would be prudent for him to return [to India] and set up business here,” says Houston.

And there was enough opportunity or so it seemed. A 2011 report by Greenpeace said India’s telecom sector emitted 5.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, accounting for 2 percent of domestic greenhouse gas emissions, thanks to its enormous appetite for diesel. Early in 2012, the central government asked telcos to ensure that by 2020, at least 75 percent of towers in rural areas and 33 percent in urban areas should run on hybrid power. This gave Carbon Masters enough reason to set their eyes on the telecom sector.

undefinedCarbon Masters processes about 35 tonnes of wet waste. It is eyeing ₹30 crore in annual revenue in three years[/bq]

But what seemed like a land of opportunities turned out to be a quagmire. “We did about three months of pro bono work for a telecom tower operator towards the end of 2012. But they got the work done, and didn’t give us any contract. It was hard for me to digest that,” says Narayan. “We decided not to do consulting engagements in India. I believe consulting work in the climate change space goes to the Big Four accounting firms or companies that can get regulatory clearances.”

It was also a time when the garbage crisis in Bengaluru was at its peak: As villages around the city’s landfills began to protest, waste disposal within the city got held up, causing massive garbage pile-ups. Amid the stench, Narayan and Houston got the whiff of an opportunity to process wet waste to generate biogas, bottle it and sell the gas to businesses.

“For telecom contracts, you have to ensure an uptime of 99.9 percent. We didn’t know how to do that, and failure would entail a fine,” says Narayan. “The next option were kitchens. Back then, commercial LPG cost about ₹118 per kg and we could compete on that front.”

In February 2013, they made a deal with Maltose Agri Products Pvt Ltd to operate the company’s biogas facility—it had a capacity of 200 kg a day—in Doddaballapura. Running the pilot project was essentially to identify potential business opportunities.

While a few pilots with restaurants and caterers were successful, running three Mahindra trucks on biogas in November 2013 catapulted Carbon Masters straight to the truckmaker’s boardroom in Mumbai. “They were the first biogas trucks in South India. The truck distributor rang up the Mahindra guys in Mumbai and told them about us. The company people then visited us on the plant,” says Houston.

Things have only looked better since. The company now also supplies CarbonLites cylinders to about eight restaurants in Bengaluru, while work is underway to reach eight more cities in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Given that CarbonLites is priced to match commercial LPG—Carbon Lites cost ₹60 per kg, while LPG costs ₹65 per kg—restaurant owners aren’t complaining either.

“There was some initial scepticism because we were new to it,” says Ram Murthy, owner of Konark restaurant, which has been using CarbonLites since 2014. “But, unlike LPG, CarbonLites cylinders maintain a constant pressure even as the content is depleted, and it does not produce carbon soot, hence no gas is wasted.”

Its asset-light model sets Carbon Masters apart from its peers, such as GPS Renewables, SustainEarth Energy Solutions, Green Brick Eco Solutions. “Startups lose their footing because they have to set up the plant, run it and then find customers. They neither have enough money to build a proper plant and bear operational expenses nor enough bandwidth for sales. The economics don’t work because eventually you cannot sell gas beyond a certain price. Hence, the model for Carbon Masters, where they just run the plant and sell the products, is impressive,” says Shyam Menon, co-founder and investment director at Infuse Ventures.

Narayan is aware of the challenges of evangelising biogas adoption in India. He admits that creating awareness about biogas is one of his biggest challenges. But, his faith in the “waste-to-value” business does not waver.

At least, his cylinders are selling.

First Published: Jan 12, 2018, 06:42

Subscribe Now