Allcargo: Proving its mettle in a tough business

The logistics company has built an enviable bouquet of offerings. Why then are the markets not impressed?

An American business sending a half-container load of goods to Antwerp, or an Indian company supplying auto parts to a car manufacturer in Gurgaon or leasing space in a logistics park could conceivably do this by entering into an agreement with just one company Allcargo Logistics. With its wide variety of offerings in the logistics space, the company has positioned itself as a one-stop shop for businesses that need to move goods quickly.

It’s a unique offering that resonates with business owners and is not something that Allcargo’s Indian rivals have been able to build. “Pre-2020, we didn’t have any presence in the domestic [logistics] market. The company now stands a lot taller in the domestic arena," says Shashi Kiran Shetty, founder and chairman of Allcargo Group. Over the last three decades he has scaled the business to a market cap of Rs 9,000 crore.

In doing so, Allcargo has emerged as the world’s largest consolidator of ocean freight in the less-than-container load (LCL) category. Its latest quarterly numbers released in February 2023 showed it had a 15 percent share of a worldwide market, which is fragmented. It now aims to start building scale in the full-container-load category, where its share is 1 percent. Together, the global ocean freight business accounts for 90 percent of topline and makes the company a play on the global trade cycle.

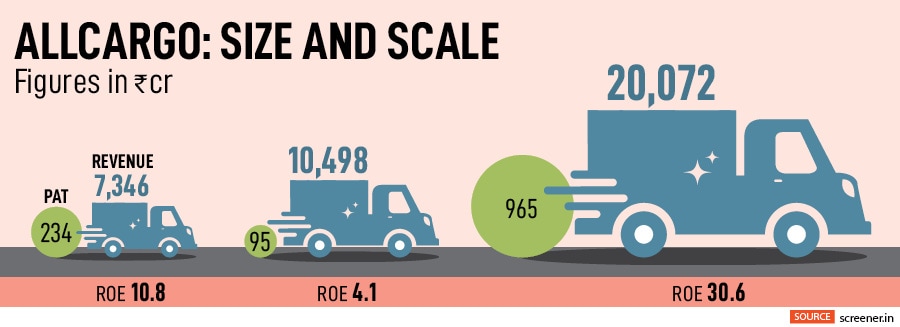

While Allcargo has clearly demonstrated its ability to scale and build a worldwide lead in the LCL business, the market has been less than impressed by the sum of its parts. Over the last five years, even as business has grown—topline has grown fourfold to Rs 20,000 crore and profitability has moved up sixfold to Rs 1,000 crore—the market has not rerated the stock. It continues to languish at 10 times earnings.

Powered by higher freight rates, there’s no mistaking the fact that in the last three years Allcargo has had a dream run. In the two years from March 2020, its revenues surged from Rs 7,346 crore to Rs 20,072 crore in March 2022. Profits rose from Rs 234 crore to Rs 965 crore. Its stock has tracked the rise in earnings, taking it to Rs 9,000 crore market cap.

But results for the December 2022 quarter showed that the market is not willing to cut it any slack. Revenue was down 19 percent to Rs 4,099 crore and profits fell 31 percent to Rs 157 crore. Shetty had addressed the lackluster numbers in an interview with Forbes India before the results were declared. “Yields are down by about 10 percent and this quarter [Q4FY23] will also be a little subdued on account of the Chinese New Year. But I expect a pick-up from next fiscal," he had said. The stock fell 12 percent on results day, but has since recovered half of what it lost.

At Rs 9,000 crore, Shetty strongly believes the company isn’t getting the valuation it deserves. One reason for this is the fact that it is now an unwieldy collection of businesses in the logistics space and investors find it hard to value the different entities. “When investors get a simple business, they know what they are investing in. Allcargo is a mix of businesses that people find hard to value," says Vikram Suryavanshi, vice president, equity, at Philip Capital. Compared to peers, it is also asset heavy and before the recent burst in profitability it had a subdued return on equity. Compared to TCI Express, which averaged 27 percent ROE in the last three years, Allcargo has averaged 17 percent.

Allcargo"s inland container depot at JNPT port, Mumbai

Allcargo"s inland container depot at JNPT port, Mumbai

The Covid-19 pandemic saw global freight rates rise dramatically. The World Container Index started climbing from April 2020, from $1,492 from a 40-foot container before peaking at $10,377 in September 2021. As global trade slows, rates have now fallen back to $2,035 in February 2023. With global trade growth slowing, it remains to be seen which way they head now. The World Trade Organization, which had forecast global trade to grow at 3.5 percent in an October 2022 forecast, expects growth in 2023 to slow to 1 percent. India’s merchandise exports and imports were both down in January 2023, falling 7 percent and 3.7 percent to $32.91 billion and $50.66 respectively.

Now, as freight rates normalise and the global trade cycle enters a low ebb, Allcargo’s prospects depend on the several strengths it has built up over the last decade. The company now effectively has four businesses: An international supply chain, express logistics (GATI), logistics parks and inland container depots. All these have strong growth prospects. Equally, they are all tough businesses to operate in, with low margins.

Since setting up Allcargo in 1993, Shetty moved rapidly to position the company for scale. The global logistics business is a tough market, where the ability to serve customers worldwide is a crucial differentiator. Over the years, the company has moved to make sure it can deliver to any part of the world. So, if a customer wants to send a small load to an island in the Pacific or a small country in Africa, Allcargo will be able to get the delivery done.

While one part of the business relies on working with shipping lines, the more crucial part is having a worldwide network that can ensure reliability. To do this, Allcargo has relied on acquisitions with the most important being ECU Line NV, in which it acquired a 33 percent stake in 1995. ECU was then the world’s second-largest LCL consolidator. Over the years Allcargo has done 19 acquisitions, with recent ones strengthening its position in Germany, a crucial market. The group has also set about an ambitious target of doubling its business in the LCL space by 2030.

Size also ensures it is able to cut out agents in several markets, explains Shetty. Often, agents compete among themselves, and this harms the business. Taking bookings directly gives the business a level of control over demand and allows it to negotiate better with shipping lines. In the first six months of 2023, the company plans to develop an 100 more trade lanes, in addition to the 2,600 they have at present. A trade lane is one shipping route so, New York to Rotterdam would be one trade lane.

Size also ensures it is able to cut out agents in several markets, explains Shetty. Often, agents compete among themselves, and this harms the business. Taking bookings directly gives the business a level of control over demand and allows it to negotiate better with shipping lines. In the first six months of 2023, the company plans to develop an 100 more trade lanes, in addition to the 2,600 they have at present. A trade lane is one shipping route so, New York to Rotterdam would be one trade lane.

With its global heft, not only can Allcargo invest in the ERP systems required but can also reach out to customers asking them to bring their worldwide business over to them. “Everyone [within the company] has proper use of our customer relationship management system. We monitor weekly call reports, and top management calls customers, focusing on the difficult task of asking why they won’t do business with us, and working on getting them on board," says Tim Tudor, chief executive at ECU Worldwide. Tudor also points out that only 30-35 percent of their performance is a result of the rise in freight rates globally. The rest has come about through efficiency.

In the domestic market, Allcargo acquired GATI in 2020. This allows it to compete in India’s express logistics market. GATI suffered from an asset-heavy model, where it owned its trucking fleet—now a rarity in the industry. Here too Shetty moved rapidly to make sure the business becomes asset-light to allow it to compete with the likes of Mahindra Logistics and Safe Express. Its truck fleet was sold and the company now leases them for its operations and has plans to get into the contract supply chain business. Shetty plans to grow this business to a billion-dollar topline in the next two to three years. This would take GATI to the top three in India. The current topline is Rs 1,500 crore in the year ended March 2022.

In addition, Allcargo has an inland container depot business as well as logistics parks and equipment hiring. These two businesses have an annual revenue run rate of Rs 1,100 crore, or about 5 percent of topline, but Shetty plans to keep them as they’ve developed an expertise in scouting for real estate and then building warehouses. The one change would be to sell the assets once built to lessors like Blackstone and then lease them back for their use. (Allcargo sold the equipment hiring business to JM Baxi in March 2022.)

Allcargo plans to split into four separate listed entities and is expecting court approval for the demerger to come by May 2023. The mainstay international ocean freight business will be the largest entity. Gati (already separately listed), logistics parks and container freight stations will form the other three entities. Allcargo has also reduced debt in the last six months by Rs 443 crore to Rs 1,874 crore. It remains to be seen how the demerged business does in the markets.

In the three decades since he set up Allcargo, Shetty has built an enviable global business that is a leader in at least one category, the LCL space. A favourable global trade cycle and asset-light businesses could also see him get the better of the valuation conundrum the group has been facing.

First Published: Feb 21, 2023, 14:45

Subscribe Now