Can edtech keep up its momentum after Covid-19?

Pandemic lockdowns have boosted India's edtech startups such as Unacademy, Byju's and Vedantu, and the wealth of their founders. But what happens once the crisis ebbs?

A student attends an online class using his smartphone in Srinagar, Kashmir

A student attends an online class using his smartphone in Srinagar, Kashmir

Image: Idrees Abbas / Sopa Images / Light rocket via Getty Images[br]Tanushree Nagori recalls a conversation she had with one of her users—a teenage girl from a small village near Saharanpur in northern Uttar Pradesh. Her father, a paddy farmer, had scrambled together funds to make their first ecommerce purchase, a smartphone, so that she could study online and not interrupt her education when the coronavirus crisis set in. “The majority of our users are children of farmers, labourers, vegetable and fruits vendors, cooks and hawkers. For them, education provides an escape velocity. It puts them in a different orbit altogether,” says Nagori, co-founder of Doubtnut, an app that lets users upload pictures of their math-related queries, and receive step-by-step video solutions within moments. It’s backed by marquee investors, including China’s Tencent, Sequoia India and the Omidyar Network.

Talk of Doubtnut being acquired by Byju’s has been doing the rounds for months now. The Bengaluru-based online learning giant is reportedly in late-stage talks to snap up the startup—it had $23,000 in revenue in FY19—for $100 million. The value of the rumoured, all-cash deal proves just how hot the edtech sector is at present. Byju’s itself has had a bountiful year: It has seen 25 million new free users on its platform since March, when the lockdown was announced total number of users are now 70 million—of which 4.5 million are paying subscribers—which is almost 30 percent of India’s 250 million school-going children.

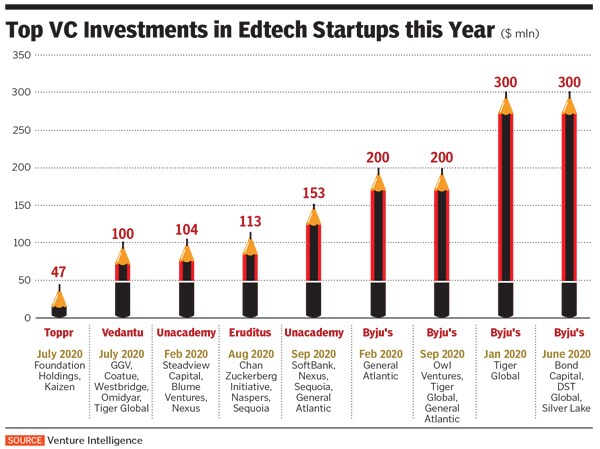

Investors have poured in around $1 billion dollars in the startup this year, catapulting Byju’s valuation from $7.8 billion in January when it raised $200 million from Tiger Global to around $11 billion in June when it raised $300 million, led by Bond Capital, a venture firm founded by Mary Meeker, who’s known for her bets on Facebook, Uber and Airbnb.

“The pandemic has brought online learning to the forefront, making it an integral part of mainstream learning,” says Byju Raveendran, founder and CEO, Byju’s. The 39-year-old eponymous founder along with his wife Divya Gokulnath, 34, who runs the company with him, are the youngest billionaires to feature on the 2020 Forbes India Rich List, with an estimated net worth of $3.05 billion.Unacademy and Vedantu are the other front-runners in the funding race. The former turned unicorn after a SoftBank-led $150 million infusion this September, while Vedantu raised $100 million in Series D funding led by US-based Coatue and Shanghai’s GGV Capital at a $600 million valuation.

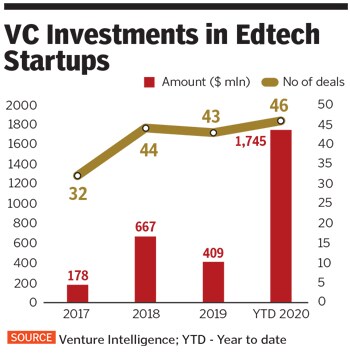

Other startups in K-12 as well as the post K-12 segment have also attracted funding, including Toppr, Classplus and Eruditus. In all, more than $1.7 billion in funding has flowed into India’s edtech sector in the first nine months of 2020, a 4x jump from the $409 million that was invested in the whole of 2019, according to Venture Intelligence.

Meanwhile, new startups have sprung up and smaller ones have been snapped up. Unacademy, for example, made four acquisitions this year. It bought PrepLadder, a medical education platform for $50 million and coding platform CodeChef in June, as well as online exam prep startup Kreatryx in March. Most recently, it picked up a majority stake in K-12 platform Mastree for $5 million. Byju’s splurged $300 million in an all-cash purchase of coding company WhiteHat Jr in August.

Before the pandemic, RedSeer, a consultancy, had predicted that the K-12 edtech space was poised to reach $1.7 billion by 2022, while the post-K-12 market would touch $1.8 billion, a growth of 6.3 times and 3.7 times, respectively, compared to 2019. “We’re now revising our estimates to factor in the pandemic,” says Abhishek Gupta, senior consultant, education technology, RedSeer.

“Covid has been a watershed moment for edtech as a whole,” says Arjun Mohan, India CEO of upGrad, the Ronnie Screwvala-founded startup that focuses on the post-K-12, higher education market.

Sure enough, subscribers have surged, investor interest is on the upswing and valuations have zoomed. But can the momentum be sustained post-Covid-19, when schools reopen and professionals trudge back to office leaving them with little time to pursue online offerings?

“Edtech is not a flash in the pan,” says Sajith Pai, director at Blume Ventures, a Mumbai-based entity that backed Unacademy in 2015. The underlying drivers, he explains, are strong. Education is seen as a path to prosperity technology solves the problem of access to quality education, especially in small towns, and rising incomes are leading to an increase in demand for private tuitions. Add to this the proliferation of low-cost smartphones, cheap data, and better infrastructure and it’s clear that edtech was always poised to grow. Says Vamsi Krishna, co-founder and CEO of Vedantu, “Edtech has been growing for the last few years. We were always going to get to this point, but what would have taken two to three years has now happened in four or five months.” Covid-19 has been the “catalyst” that helped bring about a shift in attitudes towards online learning, he says.So it’s unlikely that what happened in the foodtech space in 2015—when entrepreneurial activity surged, investor interest bubbled and funding flowed freely, only to see a slump and market consolidation in 2016 and 2017 when startups like Tiny Owl folded up—or in the hyperlocal services space, will happen in edtech as well.

While foodtech and hyperlocal services startups operate on wafer-thin margins, the gross margins in edtech are 60 to 80 percent. That’s because the average revenue per user (ARPU) is high. In upGrad’s case, it’s about ₹2.5 lakh, while for K-12 companies it ranges from ₹50,000 to ₹2 lakh. Although, counterintuitively, customer acquisition costs have not reduced through the pandemic because most players amped up their sales and marketing spends to draw in more students, the unit economics are still attractive. Plus, the target market is huge, and largely untapped. According to RedSeer’s Gupta, penetration for paid K-12 online learning is just about 2 percent in India. “We’ve merely scratched the surface,” he says.

That said, most believe there will be a dip in growth post Covid-19. “Nobody expects to grow at this pace going forward... things will slow down,” says Krishna. Vedantu, he says, has been seeing 400 percent growth month-on-month since March. upGrad’s Mohan concurs. Traffic, he says, surged 5x to 6x in the early months of the pandemic over time it has settled to 3x to 4x.

Yet others believe that while the number of users might not fall, the average time spent on the platform will go down. “As schools reopen, kids have less time on hand to spend on their devices, so naturally time spent on edtech platforms will fall,” says Nagori. But a complete drop-off is unlikely because many—like the farmer’s daughter from Saharanpur—have made an “investment for the future” by buying digital devices. Currently, Doubtnut’s 1.5 million daily active users spend about one hour per day on the platform, she says, adding that the startup added long-form live and pre-recorded classes to its offerings in June.

Krishna Kumar, founder and CEO of Simplilearn, a digital skills training provider set up in 2010, says while Covid-19 provided them with “tailwinds”, it was “not such a big game changer” as it was for companies operating in the K-12 space. Covid-19 has helped increase the size of their target market as professionals who are working from home or whose employers have shuttered operations have realised the need to acquire new-age skills in order to be desirable at the workplace, he explains. “It’s a mindset shift that has come about, which is unlikely to reverse,” he says.

“Whether or not you can sustain your growth after Covid-19 depends on how you spent the last six to seven months,” says upGrad’s Mohan, who previously served as chief business officer at Byju’s. If it was spent on product improvement and strengthening one’s sales and marketing efforts, then it’s unlikely that users will drop off, he reckons. “Covid-19 gave the edtech sector an opportunity to service customers who had never used such platforms before. If their experience was good, they’ll stick on,” he adds. A concerted push on the sales and marketing front is also important, he says, because edtech’s high ticket prices mean that customers need “hand holding”. When asked about the hard-sell and aggressive tactics used by some companies, Mohan says, “In India, if you want to sell at a high ARPU, it needs to be an assisted purchase, which leads to continuous follow-ups. When you’re building for scale and managing large teams, discipline and processes need to be set.”

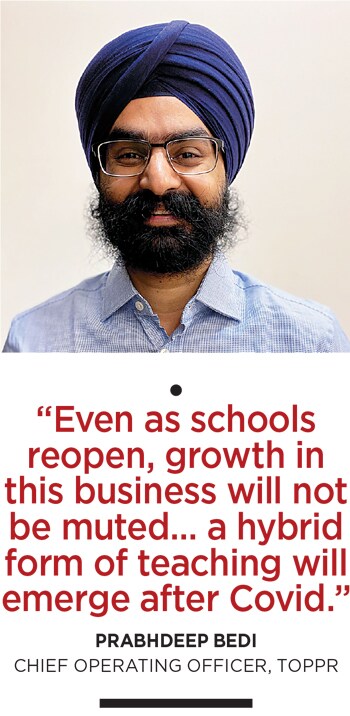

However, Toppr’s chief operating officer Prabhdeep Bedi differs. “There’s no reason for hard-sell if your product is good. Parents are not going to buy a product because some sales guys instilled in them the fear of missing out in a two-hour demo session. In the short term you might get users, but edtech is ultimately built on referrals. If users like your product, they will talk to others about it.” Toppr, which raised $47 million led by Dubai-based Foundation Holdings in July 2020, has seen a 4x growth in users since February. The paid user base has also jumped 2x, says Bedi.

Toppr also launched a school operating system business during the lockdown to help schools teach online, create assignments and manage the backend. A hundred schools and one lakh students are using the platform on a daily basis. Even as schools reopen, growth in this business will not be muted, says Bedi, as a hybrid form of teaching will emerge after Covid-19.

So despite the “frothy” valuations—about 20 to 25 percent higher than what they should be, says Pai—and the growing roster of startups (around 20 percent of the pitches Blume now receives are edtech related, up from 8 to 10 percent pre-pandemic), edtech is set to become increasingly mainstream. Says Pai, “Edtech is to India what ecommerce is to China.”

First Published: Nov 02, 2020, 13:41

Subscribe Now