As a result, the company corners much of the market share in India, having recorded around 1.5 billion bookings on the platform, translating to over 28 million in a week, before the pandemic wreaked with the economy. While the ride-hailing business is slowly limping back to normalcy, the canny Aggarwal also used the past few months to diversify Ola’s business into the fledgling electric vehicle industry in India.

“The need to transform mobility to electric is there, and we can see what"s happening with pollution, so we have to build for the future paradigm, we have to build for future technology, and in mobility, it has to be electric," Aggarwal had told Forbes India in March. “It absolutely has to be done as fast as we can."

Since then, the company has been working at a breakneck pace, and in nine months since it announced its plans to build what’s touted as the world’s largest two-wheeler factory, Aggarwal launched the first of its two-wheelers from the company’s stable—the Ola S1 and Ola S1 Pro, which it hopes will help kickstart a much-needed electric vehicle revolution in India.

“Ola S1 comes at a revolutionary price of Rs 99,999 onwards," Aggarwal said at the time of launch. “In states with active subsidy grants, Ola S1 will be much more affordable than many petrol scooters. For instance, after state subsidy in Delhi, the S1 would cost just Rs 85,009 whereas in Gujarat it would be only Rs 79,000."

![]()

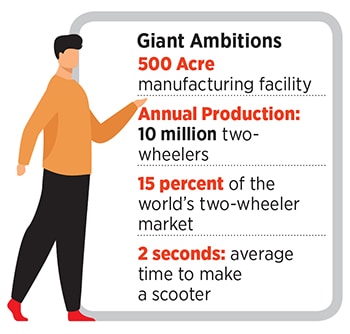

The company is also building a Rs 2,400 crore plant in the tiny hamlet of Krishnagiri in Tamil Nadu with a production capacity of 10 million vehicles annually. That’s as much as 15 percent of the world"s two-wheelers. The company’s 2 million square feet factory will have the capacity to roll out one scooter every two seconds. For now, only one of its 10 lines is operational and Ola expects to complete building its manufacturing facility by June 2022.

“The mobility space is such that no one company can transform," Aggarwal had told Forbes India in an interview earlier. “It’s a massive space and it needs a massive transformation where the whole ecosystem has to work together."

![]() Already, Ola received upwards of 100,000 orders the day it had opened its booking, in late July. While the company hasn’t divulged the total orders it has received so far, it plans to start delivery from October. “About 80 percent of the vehicles sold in India today are two-wheelers and despite that only 12 percent of India owns a two-wheeler," Aggarwal had said at the time of the launch. “These vehicles consume 12,000 crore litres of fuel every year and are responsible for 40 percent of air pollution."

Already, Ola received upwards of 100,000 orders the day it had opened its booking, in late July. While the company hasn’t divulged the total orders it has received so far, it plans to start delivery from October. “About 80 percent of the vehicles sold in India today are two-wheelers and despite that only 12 percent of India owns a two-wheeler," Aggarwal had said at the time of the launch. “These vehicles consume 12,000 crore litres of fuel every year and are responsible for 40 percent of air pollution."

Ola’s push towards electric also comes at a time when fuel prices, particularly petrol prices that most scooters and two-wheelers use in the country, have hit record prices. In Mumbai, a litre of petrol currently costs Rs 107.

The newest launch from Ola is a scooter based on AppScooter, an electric vehicle developed by Netherlands-based Etergo BV that the company had acquired in May 2020. The product, of course, has been customised for the Indian market. “Is there any other way?" Aggarwal, chairman and group CEO of Ola, had asked about the pace at which the company is planning its EV foray. “In the EV space, the only way we can create impact is to play the scale game. We must build this business at scale. That’s the only way the adoption of EVs will be faster. Because, unless we build at scale, you can"t bring the cost down enough, and you can"t get consumers excited."

So, can it bring a revolution?

To begin with, the company’s pricing strategy seems on course to shake up the industry.

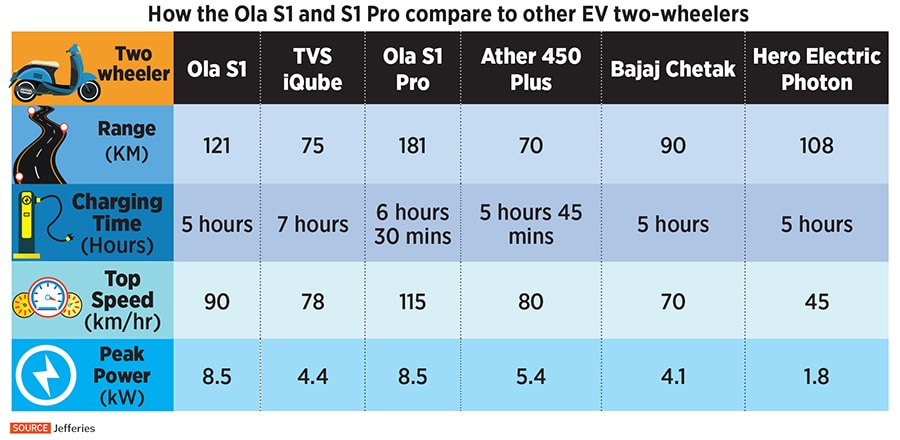

“Ola Electric"s scooters are priced aggressively with S1 at Rs 85,000 ex-showroom Delhi post subsidies," Jefferies said in a recent note. “This is 11 percent below TVS iQube, 25 percent lower than Ather"s 450X, and 41 percent below Bajaj"s Chetak. On-road Delhi price for S1 is just 10-15 percent above top-selling ICE scooters such as Honda Activa and TVS Jupiter. S1 Pro is priced at Rs 110,000 ex-showroom Delhi post subsidies, which is 29 percent higher than S1."

![]()

That could be a trigger in getting customers excited, and in providing an alternative to the internal combustion engines, something that Aggarwal knows is key for his plan. More so when the vehicle offers performance on a par with ICE engine vehicles. For instance, an industry-leading vehicle such as the Honda Activa has a top speed of around 85 km per hour with a mileage of 55 km per litre. The Ola S1 has a top speed of 90 kmph while the S1 Pro has a top speed of 115 kmph. The vehicles also have a range of 121 km and 181 km, respectively.

For years now, India’s consumers have been wary about embracing EVs despite a mammoth push from the government. India is a signatory to the Paris Climate Agreement, which means that the country needs to reduce its carbon emissions by around 35 percent of its 2005 levels by 2030. The government has tried everything—from tax cuts to manufacturing incentives in the automobile sector—to kickstart an EV revolution in the country.

Yet, despite all the narrative around EVs, there haven’t been substantial gains. Last year, India sold some 156,000 units of EVs, of which 126,000 were two-wheelers. In contrast, over 21 million vehicles that run on internal combustion engines (ICE) were sold in FY20, of which 17 million were two-wheelers. China sold some 1.3 million EVs in 2020, according to Singapore-based market research firm Canalys, in a year marked by a pandemic, accounting for over 40 percent of the global EV sales.

“Ola S1’s pricing is quite competitive and strategic in nature," says Harshvardhan Sharma, head of auto retail practice at Nomura Research Institute says. “It is in line with the segment leaders in ICE space and few notches below its EV peers. Such price positioning is good for all players in the long term because this will propel an EOS (economy of scale) effect eventually leading to an uptake in adoption and eventually growing the ecosystem. It’s remarkable that Ola can offer a truly global product at such an aggressive price point."

It has also helped that in June, the Narendra Modi government had revised the FAME-II scheme, increasing the electric two-wheeler incentive to Rs 15,000 per kWh (up from Rs 10,000 earlier) and doubling the subsidy limit to 40 percent of the two-wheeler’s price. That means any two-wheeler with an ex-factory price of up to Rs 1.50 lakh will be eligible for a maximum FAME-II subsidy of Rs 60,000 if it has a 4-kWh battery. The Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and EV (FAME) scheme was launched in 2015 and provides subsidies and upfront incentives on the purchase of EVs. Then there are various state-wise incentives for electric vehicles.

“As far as the pricing strategy goes, Ola is on par with ICE products and, with contribution from central government and state governments, it has the potential to shake things up," says Puneet Gupta, director for automotive sales forecasting at consultancy firm IHS Markit. “But, as far as the Indian consumer goes, Ola really needs to communicate the pricing well instead of confusing them with various subsidies and tax benefits. If pricing is so complex, people will move from them."

Gupta also reckons that the product could have been cheaper by at least Rs 5,000 or Rs 10,000 considering the high levels of localisation in India. “They could also be a lot more transparent and choose to claim the incentive directly from the government," adds Gupta. “This was what Maruti did with its Hybrid scheme so that the customers aren’t confused."

For now, as much as 90 percent of the components required to manufacture the two-wheeler will be built at the facility in Tamil Nadu. Barring the battery cells, which the company is importing from South Korea, the rest of the components that go into manufacturing the bike will be sourced from the company’s massive supplier park being built along with the facility.

Big plans

Ola is also setting up a series of charging networks across the country as part of its plans to fix range anxiety. While Ola’s scooters have a range between 121 km and 181 km based on the model, charging stations are critical for the success of electric vehicles in the country. According to the Central Electricity Authority (CEA), India has 933 public charging stations across the country as of June 2020. Of that, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka have the highest numbers with 433, 160, and 126 units, respectively.

Ola’s Hypercharger Network, the company claims, will be the widest and densest electric two-wheeler charging network in the world, with more than 100,000 charging points across 400 cities. In the first year alone, Ola is setting up over 5,000 charging points across 100 cities in India, more than double the existing charging infrastructure. The company is also spending some $2 billion over a period of five years for that.

“The key is getting the economy of scale, and plans to manufacture at large scale is definitely in the right direction," adds Sharma. “That is, as long as enough demand can be generated for the finished goods. Reduction of prices and wider adoption is going to be a shot in the arm from a domestic market perspective, but I am sure Ola would be considering exports as well since the product is quite global and EV scooters are going to be ubiquitous globally."

According to Niti Aayog, the country’s EV financing industry is projected to be worth Rs 3.7 lakh crore in 2030, about 80 percent of the current retail vehicle finance industry. Between 2020 and 2030, the estimated cumulative capital cost of the country’s EV transition will be Rs 19.7 lakh crore across vehicles, electric vehicle supply equipment, and batteries (including replacements).

“Ola has the potential to shake things up," Gupta of IHS adds. “Initially, it will be the urban customer who is tech-oriented who will take to the two-wheelers. But, with the way they have gone so far, especially with meeting all their timelines with the second wave of Covid, everybody has begun to feel the heat. The Ola brand is an old one and it infuses some trust and confidence compared to other startups."

It has also helped that barring a few newcomers in the sector, many of the incumbents have also been slow towards their electric vehicle play. “TVS and Bajaj Auto launched their first electric scooters 1.5 years ago but need to enhance their offerings," Jefferies note in their recent report. “Hero MotoCorp (HMCL) plans to launch a fast-charging electric scooter by March 2022 and another EV with battery swapping in the latter part of 2022. HMCL also has a 35 percent stake in Ather Energy, which launched its first electric scooter in 2018. Honda surprisingly has not launched an electric scooter in India yet despite its dominant 50 percent market share in ICE scooters."

![]()

But, despite that, the incumbents aren’t likely to let Ola go without a fight especially since Ola has managed to price its two-wheelers closer to the ICE vehicles. Honda Activa, manufactured by the Japanese automaker Honda, sells at between Rs 67,000 and Rs 71,000. Hero Maestro Edge, manufactured by Hero MotoCorp, sells at between Rs 71,000 and Rs 79,000 without taxes. “But once Ola launches its bike, there will be a price war that will start with the big players," Gupta adds. “Big players like Honda and Bajaj won’t make it easy for them."

What, then, will determine Ola’s success in the coming months? “Ola Electric"s ability to scale up manufacturing, ensure product quality and create a wide distribution network would be crucial to its success," Jefferies says in its report. “However, the bigger onus is now on incumbents to leverage their R&D, manufacturing, and distribution to scale up in EVs."

Aggarwal knows how to take a fight head on. And, for Ola Electric, he knows he is in for the long haul. "‹

Already, Ola received upwards of 100,000 orders the day it had opened its booking, in late July. While the company hasn’t divulged the total orders it has received so far, it plans to start delivery from October. “About 80 percent of the vehicles sold in India today are two-wheelers and despite that only 12 percent of India owns a two-wheeler," Aggarwal had said at the time of the launch. “These vehicles consume 12,000 crore litres of fuel every year and are responsible for 40 percent of air pollution."

Already, Ola received upwards of 100,000 orders the day it had opened its booking, in late July. While the company hasn’t divulged the total orders it has received so far, it plans to start delivery from October. “About 80 percent of the vehicles sold in India today are two-wheelers and despite that only 12 percent of India owns a two-wheeler," Aggarwal had said at the time of the launch. “These vehicles consume 12,000 crore litres of fuel every year and are responsible for 40 percent of air pollution."