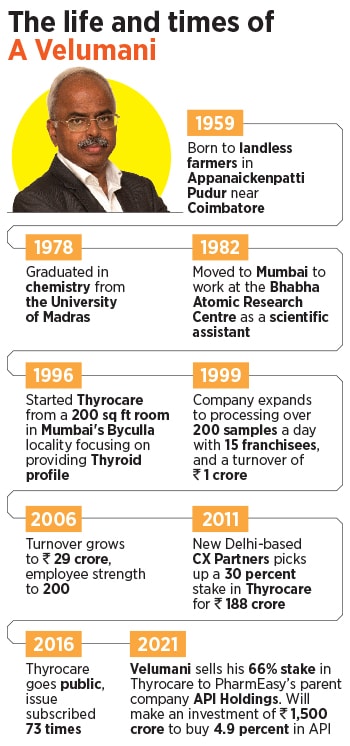

The son of a landless farmer, whose father couldn’t afford to buy him a pair of pants or slippers, Velumani has traversed some rather difficult terrains since starting out from the nondescript village of Appanaickenpatti Pudur near Coimbatore. Along the way, the bespectacled scientist had also redefined the medical diagnostic industry in the country.

His 26-year-old company Thyrocare Technologies is one of India’s largest healthcare diagnostic chains that has been instrumental in India’s long drawn fight against Covid-19 for over a year now. “Mine is a story of grit, guts and glory," Velumani, the chairman and managing director of Thyrocare Technologies had told Forbes India in an interview a few months ago. His company is today worth a staggering Rs 7,000 crore and Velumani’s own stake in that venture used to be around Rs 5,000 crore.

Until last week.

On June 25, Velumani surprised the world when he decided to sell his company to a relative newcomer in the health industry and a unicorn, PharmEasy, in one of the first instances of a startup buying a listed company. According to the deal, Velumani sells his 66 percent stake for Rs 4,546 crore to PharmEasy"s parent company API Holdings. He will use Rs 1,500 crore of those proceeds to buy 4.9 percent in API, which will propel PharmEasy’s valuation from Rs 13,390 crore ($1.8 billion) to over Rs 29,700 crore (roughly $4 billion).

“I would have retired now, had I been in my previous job," the former scientist at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre tells Forbes India. “The difference is my former colleagues have retired with maybe Rs 5 crore, and I have done so with Rs 5,000 crore."

Thyrocare, a pioneer in the thyroid testing segment, has, over the past few years, expanded its business into other areas, like preventive health checkups and lipid profiling among others, with outlets across India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and the Middle East. The company processes over 920 million samples in the country through 3,300-odd collection centres across 800+ towns in the country, making it one of the largest health diagnostic labs in the country. As India battled both its first and second wave of Covid-19 cases, Thyrocare was at the forefront, processing some 35,000 samples a day.

“A lot of people are calling me mad for leaving the company," says Velumani. “But I saw great value for the company in the deal. I felt there was huge potential for the company and maybe I am not the right man to lead it. People with an ego wouldn’t have done that."

PharmEasy’s deal with Thyrocare comes at a time when India’s online pharmacy segment has seen increased traction. Earlier this month, Tata Digital, a subsidiary of Tata Sons, announced it was acquiring a majority stake in 1mg Technologies. “It’s like an arranged marriage, “Velumani says about the deal. “About 25 boys had come to see, and with the 26th boy, it was love at first sight. The process was very fast, and I don’t see it as something where I am parting with it entirely. But the brand must transition for another 25 years, and it can do that better without me."

From landlessness to billionaire

Velumani’s story is one of true grit. The son of a landless farmer, he grew up near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu. “When it comes to poverty, there are two kinds of people," Velumani had said during the interview a few months ago. “One who enjoys it, and another who suffers because of it. The one who enjoys it will come out of poverty very fast while the one who suffers will remain poor."

His parents toiled hard to bring up Velumani and his three siblings and ensured they received an education. His mother, Velumani says, inculcated the lesson of not borrowing money, and taught him to manage with limited resources. “People in business often forget how to manage with low resources, but I learnt how to manage with no resources," Velumani says.

After his graduation in chemistry in 1978, Velumani’s career began with a job as a shift chemist at Gemini Capsules, a small pharmaceutical company in Coimbatore, in 1979. Three years later, the company shut down and Velumani was staring at an uncertain future.

![]() Around the same time, Velumani used to frequent the Central Library in Coimbatore. “It was my adda (hangout)," Velumani says. “I didn"t have money and I didn"t have many friends. My life was about spending time in libraries than in theatres or other entertainment options." There, on a Wednesday, Velumani saw a job posting in a newspaper for a scientific assistant at the illustrious Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. BARC, located in Mumbai, is one of India’s foremost multi-disciplinary nuclear research centre that began operations in 1954.

Around the same time, Velumani used to frequent the Central Library in Coimbatore. “It was my adda (hangout)," Velumani says. “I didn"t have money and I didn"t have many friends. My life was about spending time in libraries than in theatres or other entertainment options." There, on a Wednesday, Velumani saw a job posting in a newspaper for a scientific assistant at the illustrious Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. BARC, located in Mumbai, is one of India’s foremost multi-disciplinary nuclear research centre that began operations in 1954.

“I came to Mumbai, not with some big dreams," Velumani says. “My belief was that if I get a government job, my life will be completely transformed." But the entire process of selection would take time and Velumani returned to his hometown to look at other opportunities. Around 50 days later, he received an offer letter to join the institute and Velumani was once again back in Mumbai. This time, however, a medical assessment had found him to have colour blindness, forcing BARC to withdraw the offer.

“After 15 days, I received a letter saying that colour blindness will not affect your work," Velumani says. “Finally, after three trips to Mumbai in three months, I had a job at BARC." His work profile involved thyroid testing. “It"s a very boring job," Velumai recalls. “I also would have hated it had I been from a rich family. There are two kinds of people at the workplace, those who only work, and those who can also think. I was in the second category."

That meant, Velumani began spending his free hours in the library and began studying everything about the thyroid gland, endocrinology, immunology, microbiology, and molecular biology, among others. In 1985, he enrolled for a master’s degree while being an employee at BARC, before going on to complete his doctoral programme in thyroid biochemistry by 1995. “When I was travelling to Mumbai, I used to think the BSc degree was a full stop," Velumani says. He later realised it was only the beginning of his journey. It also helped that he had the support of his boss, a blind man, who also encouraged Velumani to study.

At that time, the University of Mumbai had a tie-up programme that allowed scientists at BARC to study and research further. In the meantime, he also rose to the rank of a scientist and was posted at the Radiation Medicine Centre (RMC), a department that focussed on the application of nuclear energy in healthcare and agriculture.

Building Thyrocare

By 1995, some 14 years after he started working at BARC, Velumani knew it was time to start something of his own. “My boss retired, and I was very comfortable with him," Velumani says. “At that time, my wife was working with the State Bank of India. Since she had a stable job, I thought why not give up this job and try something else. I was a very frugal man"

With Rs 1 lakh that he had pooled through his provident fund, the then 37-year-old set up a testing facility in Byculla, a neighbourhood in South Mumbai, to detect thyroid disorders. It also helped that the lab was near the Tata Memorial Hospital, a prominent cancer institute. For long, India has grappled with hypothyroidism, with one in ten Indians suffering from the condition.

Velumani started out by charging one-fourth of the existing fees in the market for processing the samples. Even at that time, the scientist-turned-entrepreneur knew the key to success was keeping costs low, which meant the business needed to process at least 25 samples a day to be cost-effective. The company would provide a thyroid profile at Rs 100. That was also largely because it focussed on aggregating samples from numerous labs in the city, thereby achieving economies of scale.

“When I priced my services very low, people asked me, "will you get enough to eat", Velumani recalls. “But I knew, if I am the lowest, and I am the best, I"ll be the tallest. There is no company that has closed down because they kept prices low. All of them closed down because they could not control the cost."

Over time, Velumani started out with a franchise model where samples would be collected across the country and sent back to the central laboratory in Mumbai. By 1999, the company had nearly 50 franchisees and processed some 200 samples a day. Until 2015, the company had only one lab in Mumbai to process the samples coming in from all over the country. “I succeeded in logistics very early on," Velumani says. “But when we found that the floor was losing efficiency as samples went up, we decided to set up a new one in Coimbatore and found the efficiency was going up but not the cost." Today, the company has 15 processing labs across the country.

In addition, from testing for thyroid, the company also expanded into other areas, including preventive medical checkups, blood tests, and pulmonary function tests. A significant part of the business, however, continued to be in the B2B category. “Velumani had taken a philanthropic approach to his business, and managed to build the business well," says Vishal Manchanda, research analyst for pharma at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “He was the one who brought down costs substantially in the testing business. In addition, his focus on operational efficiency also made him one of the cheapest in the business."

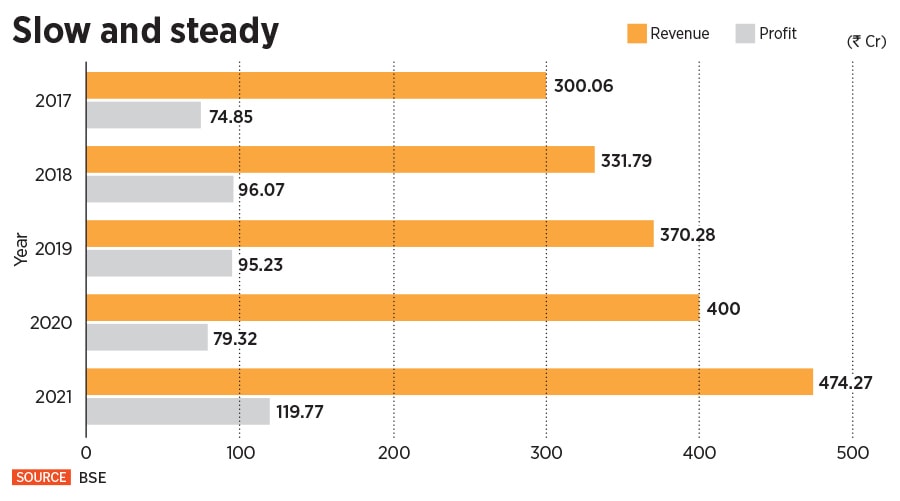

Last year, Thyrocare posted revenues of Rs 474 crore, up by 18 percent, while profits grew by 51 percent to Rs 119.7 crore. “In the entire world, India is cheapest in healthcare," Velumani had told Forbes India earlier. “And in India, I am the cheapest diagnostics provider. This is nothing but efficiency." That"s probably why Thyrocare has seen its net margins hover between 25 and 30 percent, unlike many of its peers whose net margins have remained between 15 and 20 percent. Over the years, by keeping prices low, Velumani had managed to increase volume and achieve economies of scale, while by keeping overhead costs low, he protected his margins.

![]()

In 2016, over 20 years after Velumani founded the company, Thyrocare Technologies listed on the bourses, which was subscribed some 73 times. A few years before that, in 2011, New Delhi-based CX Partners picked up a 30 percent stake in the company for Rs 188 crore. “Had I not diluted my company, I would not have become cleaner and transparent because once somebody else is the stakeholder in your organisation, he is bound to ask too many questions, and you don"t want him to ask any question which is worrying you," Velumani says about the deal.

At that time, the deal had valued the company at about Rs 600 crore ($100 million). Since then, other investors, including Samara Capital, Norwest Venture Partners, and ICICI Bank’s Emerging India Fund, had also bought into the company.

“In 2011, somebody bought a stake in the company and for five years, they did not do anything," Velumani says. “When they left, they got four times the value without doing anything. My son told me, ‘You do four times the work and somebody else gets four times the reward’. He suggested that I do what they did."

Letting it go

Perhaps that was also a trigger when it came to letting go of the company he had held close to his heart. Five years ago, Velumani had also lost his wife, who he believed was a pillar of Thyrocare. Sumathi Velumani, a former director at Thyrocare, and passed away due to pancreatic cancer before the company had gone public.

His children, a son and daughter, meanwhile felt that only Velumani could do justice to the company. “Over the past five years, I had left it to them to run it," Velumani says. “But, perhaps, they are more of managers than creators, and they felt it was not the best way to run it. A creator is somebody who dreams." He then discussed the plan of a stake sale with his children, only after he had made up his mind to sell the company. “I took a decision, and told them," Velumani says. “You must never discuss and then decide. That causes confusion."

Now, with nearly Rs 3,500 crore in his kitty, Velumani, the investor, is gearing up for the long gamble. “I used to get a salary first, and then I began paying salaries," Velumani says. “Now, I will be the one giving money to those who pay salaries," Velumani jokes about his foray into investing.

To begin with, he will own a five percent stake in API Holdings, the holding company of PharmEasy, which is likely to be listed on the bourses and is currently valued at a staggering $4 billion. PharmEasy, founded by Dharmil Sheth, Dhaval Shah, Harsh Parekh, Hardik Dedhia and Siddharth Shah, provides a slew of services including teleconsultation, medicine deliveries, and sample collections for diagnostic tests. The six-year-old company has a network of 80,000 pharmacies and 6,000 doctors.

![]() Dhaval Shah and Dharmil Sheth, co-founders, PharmEasy Image: Mexy Xavier

Dhaval Shah and Dharmil Sheth, co-founders, PharmEasy Image: Mexy Xavier

In April, PharmEasy became India’s first e-pharmacy unicorn after raising $350 million at a valuation of $1.5 billion in Series E funding led by Prosus Ventures and TPG Growth. A month later, the company purchased e-pharmacy player Medlife for an undisclosed amount. “Thyrocare is a B2B business, which has been dealing largely with hospitals," Manchanda adds. “With PharmEasy, it will have an opportunity to deal with customers directly and offer PharmEasy an opportunity to offer numerous wellness packages, making it a holistic player in the space."

Already, other players in the segment, including Netmeds, Flipkart, and Amazon, are ramping up their presence in the segment. That’s because e-pharmacy and B2B healthtech are the two largest segments in the healthtech sector in India, and account for about 70 percent of the overall healthtech market, according to a report by IAMAI and Praxis. Of this, the e-pharmacy business is worth a staggering $700 million. The past few years has seen an increased traction towards healthcare, particularly healthtech, as Covid-19 accelerated a shift towards tech-based offerings.

“E-pharmacy saw a 200 percent increase in the number of orders in 2020, e-pharmacy adoption in households also increased by more than 2x post Covid-19," the report said. “The number of consultations on teleconsultation platforms increased by 300 percent in 2020. India’s e-diagnostics market was at $0.07 billion in 2020 and is growing at a CAGR of 66 percent."

India currently has more than 5,000 healthtech startups and the healthtech market, according to IAMAI-Praxis Global Alliance, is expected to grow at a CAGR of 39 percent to touch $5 billion by 2023. “Due to physical restrictions and safety concerns owing to the pandemic, there has been an increased adoption towards tele-consultation, homecare services, e-pharmacy, online fitness and digital personal health management which has catapulted the Indian healthtech sector on a high growth path," consultancy firm, RBSA Advisors had said in a recent report. “The consumer adoption that healthtech has been able to achieve in 2020 would have taken at least 4-5 years in a non-Covid 19 scenario."

That’s perhaps something Velumani knew was a long time coming. “Anything connected with technology and tech companies will be very highly profitable, and scalable," Velumani had said about the impact of Covid-19 on the healthcare services industry in 2020. “And you will get a lot of valuation."

Looks like, the canny investor in Velumani is only getting started.

A Velumani, chairman and managing director of Thyrocare Technologies

A Velumani, chairman and managing director of Thyrocare Technologies  Around the same time, Velumani used to frequent the Central Library in Coimbatore. “It was my adda (hangout),"

Around the same time, Velumani used to frequent the Central Library in Coimbatore. “It was my adda (hangout),"