That the monsoon this year has been unusual in its onset, severity and distribution has been in the news, given the severe damage to life, property and infrastructure it has caused in the northern and northwestern regions of the country, while falling short of normal in the eastern regions. In the short term, erratic rainfall affects the sowing of crops and consequent prices of food commodities, and in the longer term, it raises the question of food security.

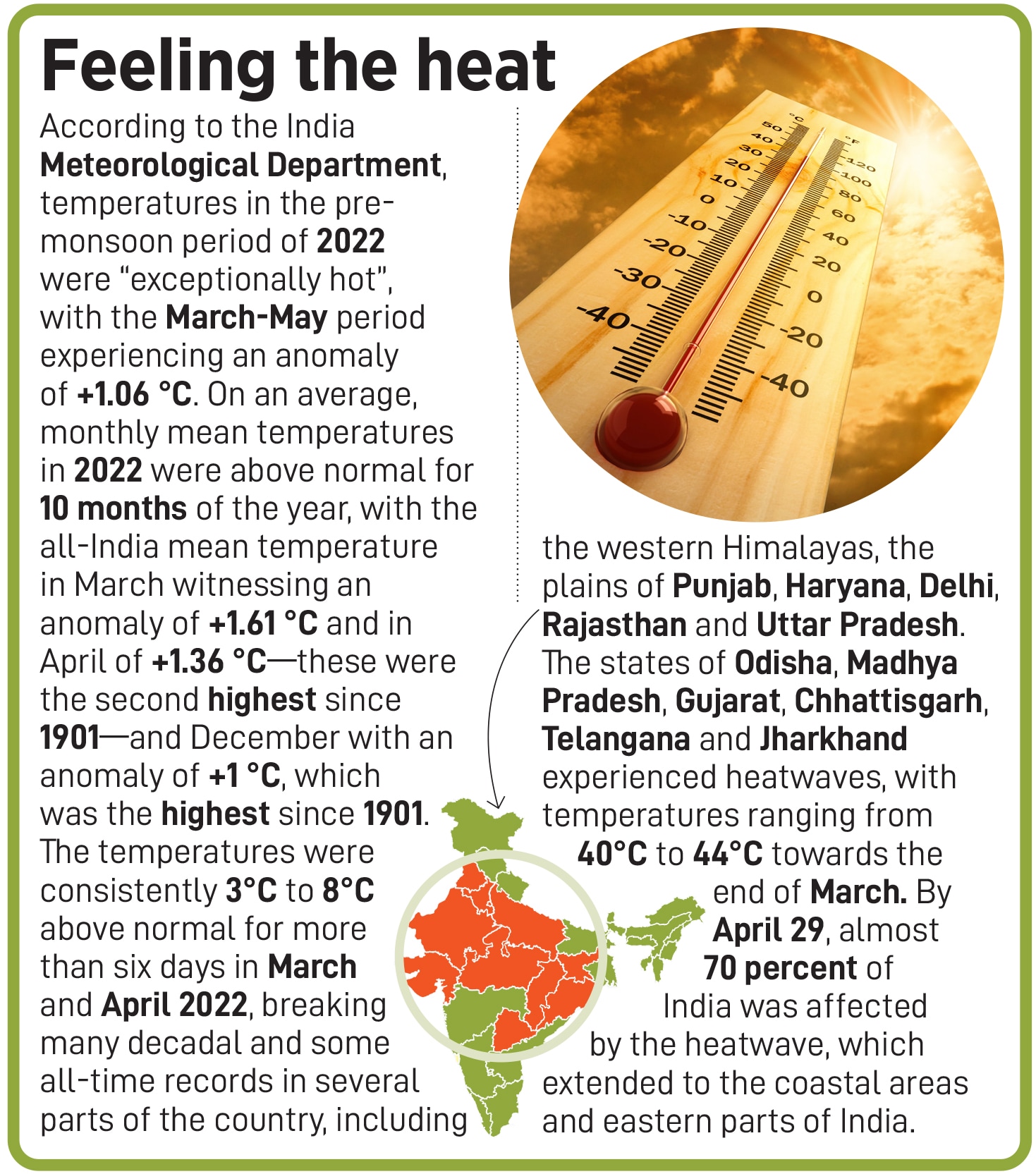

And it is not just rainfall that is at play: Extreme temperatures pose an equal threat. In a report titled Statement on Climate of India during 2022, India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences and India Meteorological Department (IMD) highlight in detail the extreme heat conditions affecting the country (see box) in the pre-monsoon months. The report concludes: “Anomalously high temperatures during these months adversely affected grain filling and caused early senescence, thus reducing crop yields, especially wheat."

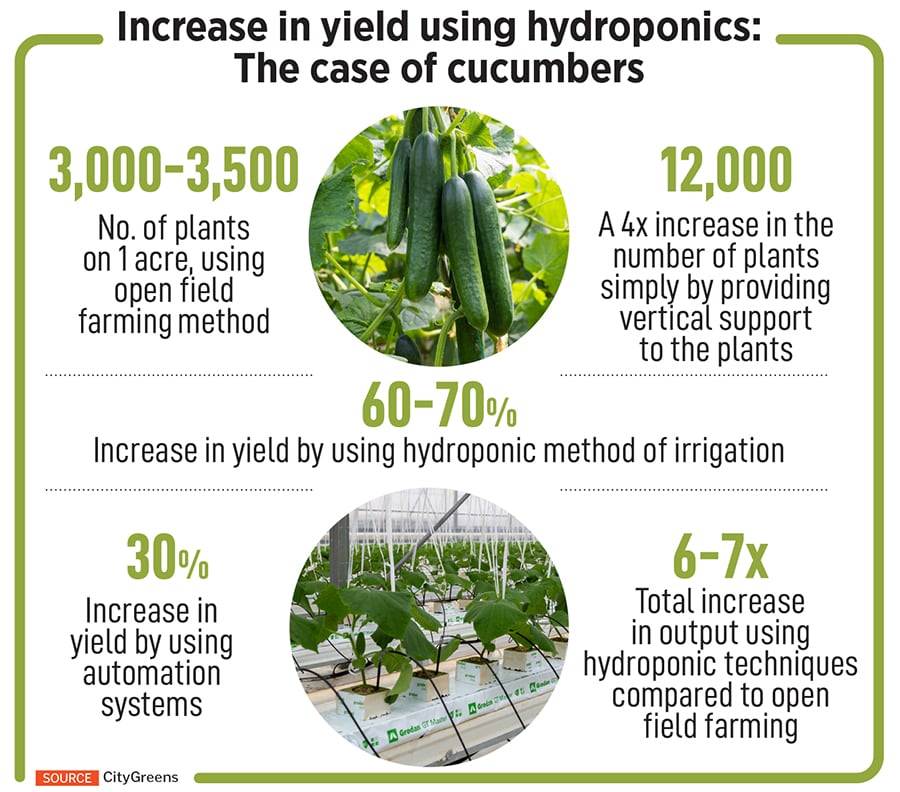

In a country where agriculture and allied sectors, according to the government, contributed 18.3 percent of GDP in 2022-23, and the farm sector employed 45.5 percent of its labour force in 2021-22, the impact of climate change on food security and employment cannot be stressed enough. In order to adapt to unpredictable weather and soil conditions, the agriculture sector is witnessing the growth of ventures that are adopting various technologies to mitigate the impact of erratic rainfall and heat, while increasing yield manifold (see box) and decreasing the use of harmful chemicals.

![]()

The new-age farmers

For ventures such as NutriFresh Farm Tech, Rise Hydroponics and CityGreens, the founders got their hands dirty experimenting with different technologies and formats before launching commercial ventures.

Sanket Mehta and Ganesh Nikam, co-founders of NutriFresh, spent about a year and a half farming on 4 acres of land that belonged to Nikam’s father—Mehta was a credit officer at Central Bank of India processing proposals for loans in the agriculture sector, while Nikam was running his own debt syndication business when they met at work—and understanding the pain points and resolving them. “During that journey, while nearby farmers would get an average yield of 60 to 70 tonnes per acre, we were able to achieve 120 tonnes per acre. And that is what gave us the confidence that, when done differently and with a little bit of knowledge, the outcome can be completely different and you can be successful," says Mehta.

The duo’s first venture was of floriculture, where they grew flowers such as roses, gerbera and orchids on 4 acres at present, this project runs completely on hydroponics. Their second project was in Phaltan, in Maharashtra’s Satara district, where they leased 250 acres from the state government, and grew sugarcane, baby corn, sweet corn, maize, jalapenos, chillies, watermelon and papaya and sold them to various corporates.

Their third project was NutriFresh—started in 2019 on 10 acres—built with the learnings from the first two projects. “We learnt that we need a sector within agriculture that is tech-based, agile, and which can yield produce around the year, irrespective of the season." The company now has 33 acres under hydroponic production and grows 40 kinds of fruits and vegetables, and has more than 100 B2B clients, including Nature’s Basket, Big Basket, Swiggy, KisanKonnect, McDonald’s, Venky’s, Amazon Fresh and Reliance Fresh.

Last May, Nutrifresh raised $5 million in a pre-Series seed funding round led by Theodore Cleary (Archer Investments), Sandiip Bhammer (Green Frontier Capital), Sky Kurtz (Pure Harvest AE) and Mathew Cyriac (Florintree Advisors and ex-Blackstone India), among others.

![]() Gaurav Narang, co-founder and CEO, CityGreens

Gaurav Narang, co-founder and CEO, CityGreens

Ahmedabad-based Rise Hydroponics—co-founded by Aggarwal, Meet Patel and Vivek Shukla—however, remains entirely bootstrapped, with no external investor. Unlike the end-to-end approach of NutriFresh, Rise sets up large-scale hydroponic and CEA farms for other companies to operate, and has so far set up 25 lakh sq ft of hydroponic farms across 12 states in India, which includes a 200-acre farm in Rajasthan and 40 acres of poly houses.

“Our farms grow everything from leafy greens such as exotic varieties of lettuces and herbs, broccoli and peppers, to Indian staples like brinjals, okra, and melons, to ayurvedic herbs such as ashwagandha and kalmeg," says Aggarwal, who went through two years of self-learning, by trying out different techniques on rooftops. He started Rise Hydroponics in April 2020, with multiple intentions: “I wanted to make agriculture a lucrative business for everyone and change the status quo that we have seen for many years, with farmers facing severe hardships in many regions. I also wanted to change the fact that the rampant use of chemicals and pesticides was giving rise to chronic diseases, not just among consumers, but also among farmers themselves, as we have seen in Punjab."

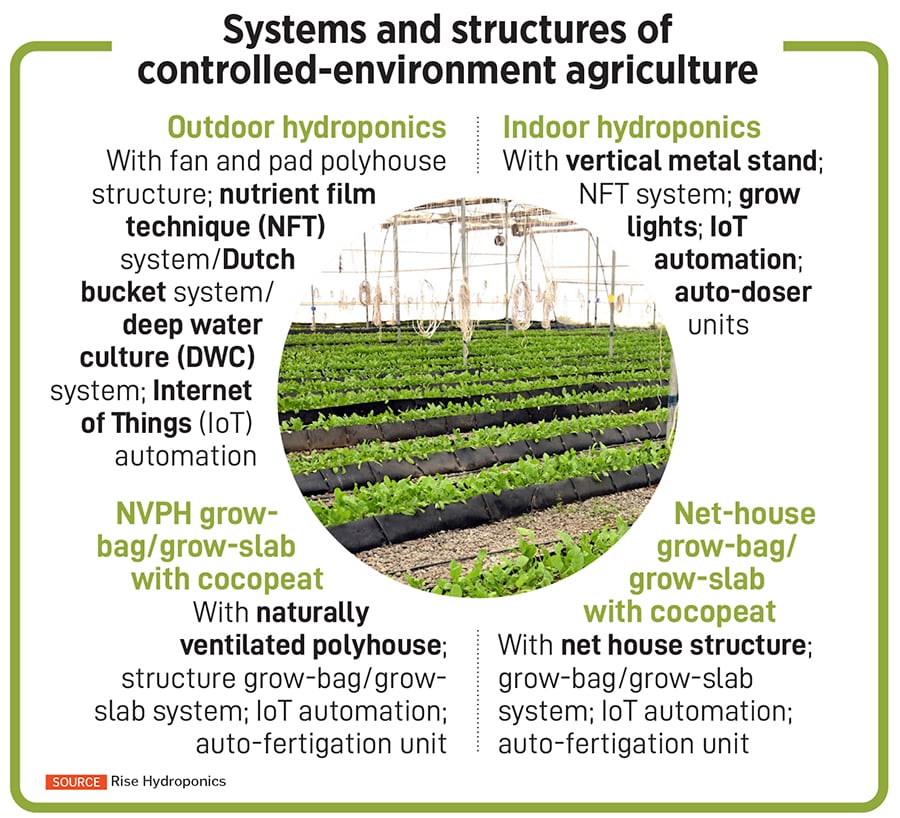

Aggarwal explains that the cost of setting up a CEA farm can vary widely, and depends entirely on the kind of technologies and structures being implemented (see box) costs can range from ₹25 lakh to ₹30 lakh for 500 sq m to 1,500 sq m. “For an investor—and a lot of private investors, including individual businesses are showing interest in this sector—the returns on investment vary from 30 to 35 percent annually, following a gestation period of two to four months."

Rise Hydroponics is a vendor for Big Basket, Star Bazaar and Waycool, and its clients include Hero MotoCorp, Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative Limited (Iffco), Tatva Greens, Satvik Greens, WaterCress Farms and Satviki Farms.

![]()

Starting with the intention of providing supply linkages between growers and consumers of healthy produce, CityGreens—co-founded by Gaurav Narang, along with wife Shwaita Uniyal, and Rahul Indorkar—has worked with different models before deciding to focus on developing and deploying cutting-edge technology at affordable rates to farmers. “We had an earlier startup in the health care domain for about nine years, which was acquired by Portea Medical. With our experience in cold chains and delivery capabilities, we wanted to form a supply chain company for healthy farm produce, but realised it was difficult to find quality food," says Narang. “We started looking for other solutions and came upon hydroponics, and thought of giving it a couple of years to develop this ecosystem. So, we put in our own money and started CityGreens in 2017."

In 2020, CityGreens ventured into the B2B sector, where it started setting up farms for commercial growers it has set up about 30 farms so far. To address the twin challenges of lack of skilled manpower and the lack of markets, it turned to creating automation solutions for all critical tasks, and tying up with players such as Big Basket and Milk Basket to provide a market to growers.

“In India, adoption of automation is very slow because the technology usually comes from the US and Israel, and is very expensive. Two years ago, we started making automation solutions and launched the automation products about eight months ago," says Narang. “Although we were operating six to seven of our own farms, we have now shut them all down. We realised we can bring in many more efficiencies with the kind of technology we have developed at an Indian price point. Compared to Israeli technology, we are at 20 percent of their cost."

Bengaluru-based CityGreens is now setting up a 3.25-acre research farm near Ahmedabad, with 12 different micro-climates for Indian crops. The technologies they thus develop will be deployed with their partner farmers. “The farm also runs entirely on renewable energy, which is another cost factor. We are using geo-thermal cooling, in which we use the deeper layers of soil to cool the air by 8-10 °C, which is then used to cool the polyhouses. For further cooling we use solar power."

Vihari Kanukollu, CEO and co-founder of UrbanKisaan, which was started in 2017 and operates greenhouses and vertical indoor farms in Hyderabad, Oman, Bahamas and Maldives and soon in the UAE and Saudia Arabia, says that although embarking on a hydroponic venture is exciting, it is not without its challenges. “Initial setup costs can be substantial, given the advanced systems and technology involved. There’s also a steep learning curve, as managing a hydroponic farm demands specialised expertise. Energy consumption, especially with artificial lighting, can be significant."

Kanukollu, Sairam Palicherla and Sampath Vinay, founded UrbanKisan to mitigate the environmental impact of traditional farming methods and the pressing need for food security in regions with land and water constraints or unfavourable farming conditions. This, while creating a sustainable and scalable solution.

![]() Vihari Kanukollu (left) and Sairam Reddy Palicherla of UrbanKissan

Vihari Kanukollu (left) and Sairam Reddy Palicherla of UrbanKissan

Investor interest

Incofin, a Belgium-based impact investment manager that has a presence in India, recently launched its Sebi-registered ₹600-crore private equity fund, with the objective to support sustainable businesses contributing to 12 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. It is investing predominantly in two sectors, financial services and agri-food. “We are an impact fund, and given one of the sectors is agri-food, hydroponics, which is under a larger scheme of protected farming, fits into our thesis," says Shubham Kothari, investment associate at Incofin. “From an environment point of view, hydroponics is a more sustainable, scientific method of farming—especially in these days, given the lack of agricultural land, fertile soil, and scarcity of water—using significantly lower amounts of water, making optimal use of land, with yields that are significantly high. Also, the output is relatively clean."

Incofin’s fund has a Rs 500-crore investable corpus. “Typically, we do five deals per sector. The fund has been closely tracking the hydroponics sector and is hopeful of making an investment in this space, either from its current fund or upcoming funds. In general, the fund expects a minimum IRR ranging from 25 to 30 percent," says Kothari.

Kothari says there are multiple business models in the sector, including companies that just construct polyhouses or hydroponic farms and sell them to farmers, and those that are doing an end-to-end process of setting up their own polyhouses, farming, and supplying to end business-business (B2B) or business-to-consumer (B2C) customers. “We prefer models with an integrated end-to-end value chain, with the right distribution strategy as these have the potential to generate higher margins. It is also important to have a diverse product offering with an optimal blend of exotic crops, leafy greens, and traditional crops. Otherwise, it could be very difficult to be financially sustainable," he says.

The two challenges that face this sector, he explains, are scalability and profitability. “It is important for us to have companies that are in the end-to-end business cycle of the entire hydroponic space." Although Incofin is yet to invest in any hydroponic venture, it is looking out.

An end-to-end operation is something that Karan Goshar, partner and co-founder of Samarthya Investment Advisors, also preferred and hence became NutriFresh’s first angel investor. “For most investors in the agritech sector, the technology element needs to be very dominant. So, the various funding rounds taking place are related to some specific problem, which some specific company is solving," he says, adding that ESG factors, too, play a significant role in influencing decision-making. “The scope that NutriFresh holds is different. Compared to many other companies, Sanket and Ganesh entered the industry with a multi-crop approach—they have 40 SKUs—were extremely price-sensitive, and from day one they wanted to be profitable and sell the entire produce at mandi prices." Macro factors such as substantial growth in the B2B model, modern and quick commerce also proved favourable where taking the produce to market is concerned.

“NutriFresh is a very asset-heavy company, and while raising Series A we realised that although PEs are looking at this sector, VCs aren’t willing to touch this asset class because of the asset-heavy nature. However, the business needs to have these assets in order to produce successfully," explains Goshar. With the fresh round of funding, NutriFresh plans to expand its total capacity to close to 100 acres in one specific location, which gives them the operating leverage.

Validating Goshar’s views on VCs’ approach towards the sector is Reihem Roy, partner at Omnivore, an early-stage VC fund that has invested in about 40 agritech startups, but none that involves CEA farms.

“From the investor standpoint, the challenges are two-fold: It is not so much as op-ex but cap-ex to get the farm up and running," he says. “Multiple models, such as franchise models and consumer models, have been explored. But the problem of capex remains. This is different from the asset-light, easy-to-replicate and scalable ventures that VCs like to invest in. Hydroponic farming includes real estate, machinery and equipment."

Roy explains that the second challenge that VCs face is the need for such farming ventures to aggregate demand, either by feeding into modern retail or plugging into a hyperlocal delivery platform. “The only approach that can maximise profits is the D2C [direct-to-consumer] route, but there too marketing and customer acquisition is a high cost." He adds that the VC fund would perhaps be more interested in agri-startups that are like aggregator platforms that provide market linkages or resolve specific pain points using technology.

The startups that Omnivore has invested in includes Ecozen Solutions (a solar cold storage solution), Aquaconnect (a tech platform that uses artificial intelligence and satellite remote sensing to bring transparency and efficient market linkages in the aquaculture sector), Loopworm (an agri-biotechnology company that converts organic wastes into valuable products), Niqo Robotics (it uses AI-powered robots in farming activities), Tractor Junction (a digital marketplace to buy, sell, finance, insure and service farm equipment) and Varaha (it generates carbon credits through tech solutions).

Kanukollu of UrbanKissan, however, has tasted success with VC investors. Although he does not reveal the amount of investments the venture has attracted, he says his investors include Y Combinator, BASF Venture Capital, 2xN and Khimji Ramdas. Markus Solibieda, managing director of BASF Venture Capital GmbH, had reportedly said that agritech was one of the key focus areas of the VC fund across the globe, and its aim is to support innovative agricultural and food-related businesses across Asia.

CityGreen initially remained bootstrapped because the co-founders believed that unless they could solve the problems, there was no point in raising money. “We did a small angel investment round, and now we feel we have cracked the market and are raising a Series A round," says Narang. “About three years ago, we had reached out to some top-rung investors and understood that they perceived hydroponics as a niche market. The middle rung was sitting on the sidelines, while the bottom rung was willing to invest. We are now talking to a US-based investor with a fund size of $75 million, which means the middle rung is coming in."

The venture is now seeing more interest from investors since it started focusing on developing technology, especially from countries such as the Gulf Cooperation Council nations and Singapore, where there is scarcity of land and water, and such cheaper technologies are in demand. “Now these investors are approaching us, instead of us approaching them," adds Narang.

![]()

The path to profitability

Although perceived as a capital-intensive, niche segment, these hydroponic farming ventures have managed to break into the mainstream by scaling up their operations, reducing the cost of equipment through indigenisation, bringing in operational efficiencies by using a bouquet of technologies, and growing a multitude of everyday fruits and vegetables instead of only exotic ones.

“NutriFresh’s entire approach was about having these massive facilities in one location, so that they’re able to achieve operational efficiency. Second, what really interested us in this investment was that they were growing 40 SKUs and wanted to give a bouquet of products to the customer," says Goshar of Samarthya Investment Advisors. “Usually, when you think about hydroponics, it’s always about exotic fruits and vegetables. But NutriFresh doesn’t do that they do the exotics, but at the same time they’re able to give every single produce that a household needs on a day-to-day basis. This has helped them in being price competitive."

“By increasing the scale of operations, we have reduced the cost by bringing in efficiencies. Apart from that, we have reduced the capex by making the required equipment in India instead of importing them, as was the case some years ago, since hydroponics was a technology that was developed in Israel," adds Nikam of NutriFresh.

UrbanKissan’s Kanukollu adds the venture is expected to become profitable by the end of this financial year. “Our focus remains on sustainable growth and creating long-term value for our stakeholders," he adds. UrbanKissan has also entered into strategic collaborations, such as a joint venture with Chirayu Khimji, director of Nailesh Khimji Investments in Oman and the UAE, through which it aims to take their technology to businesses worldwide.

CityGreens—which turned profitable six months ago—is clear that if hydroponics has to be sustainable in India, it has to grow produce that people in India eat, and sell it at a price that people in India can afford. Says Narang: “Around four years ago, in my farm in Bengaluru, I was growing lettuce and selling it at ₹160 a kg. My growing cost was about ₹50-55 a kg, and I was making good money. The moment the season turned, and a truck could come overnight from Ooty, I was not able to sell even at ₹60 a kg. Demand for exotic vegetables alone is limited, and is not sustainable."