To begin with, India’s oldest private airline will make a comeback into Indian skies next year. Around the same time, a new entrant, backed by a billionaire businessman and a few aviation veterans will also take to the skies. Yet another, backed by one of India’s oldest business groups, will tap the bourses to raise money and have already received approvals for it.

While all this plays out, India’s oldest airline and its national carrier, Air India, will have a new owner for the first time in more than 70 years. One of the suitors is an airline whose promoter has close ties to the government, but one who has seen its fortunes dwindle over the past few years, raising concerns about its viability. If all this isn’t enough, India also has a two-year-old player emerging as its largest airport operator and accounting for one in four passengers passing through its airports.

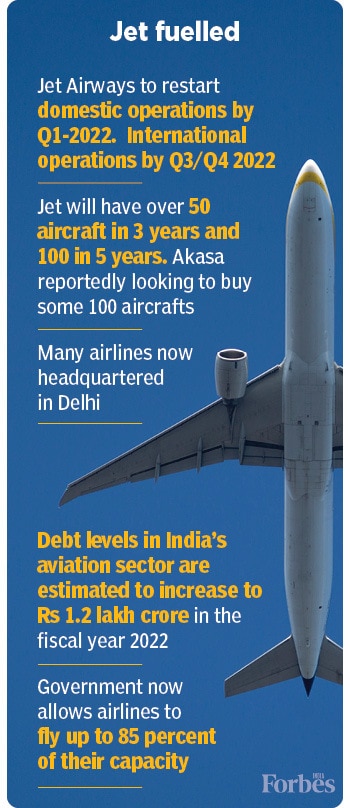

Amid this churn, India’s aviation sector is expected to see debt levels rise to Rs 1.2 lakh crore in FY22, requiring additional funding of Rs 45,000 crore in the next two years. Over the past few years, many, including Jet Airways, had fallen prey to high debt levels, making operations unsustainable. Beleaguered airline owner Vijay Mallya had to flee the country after his airline, Kingfisher Airlines, had mopped up massive debts during its decade-long journey.

“Lurching from crisis to crisis has become a familiar story since 2004 because the industry has chosen to pursue profitless growth, resulting in chronic losses for many years," said airline consultancy firm Centre for Asia-Pacific Aviation (CAPA) in its India aviation outlook for 2022. “Two major airlines have failed in the last 10 years, leaving a trail of $7 billion of liabilities. Yet nothing has changed. The twin waves and sudden impact of Covid-19 have resulted in a high level of solvency risk for most airlines, which could impact the entire industry, including airports."

But this hasn’t hindered anyone’s plans so far. Early in September, almost two years after Jet Airways was grounded, the airline announced its plans to make a remarkable turnaround by next year. For this, it is looking to tap into its once undisputed legacy and its rather loyal customer base.

“Jet Airways 2.0 aims at restarting domestic operations by Q1 2022, and short-haul international operations by Q3/Q4 2022. Our plan is to have more than 50 aircraft in three years and more than 100 in 5 years, which also fits perfectly well with the short-term and long-term business plan of the consortium," said Murari Lal Jalan, the lead member of the Jalan Kalrock Consortium and the proposed non-executive chairman of Jet Airways, earlier in September.

The airline will restart operations with a New Delhi-Mumbai flight. “It is the first time in the history of aviation that an airline grounded for more than two years is being revived and we are looking forward to being a part of this historic journey," Jalan added.

![]()

Jet Airways will begin flying domestic routes before expanding its international operations. Once owned by Naresh Goyal, it will now be run by a consortium of investors led by Murari Lal Jalan and Kalrock Capital. Jet Airways’ plans come at a time when India’s aviation industry has been hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. A report by Capa projects a loss of $3.9 billion for Indian airlines in FY22. Similarly, rating agency ICRA expects overall cash loss for the sector to be around Rs 3,500 crore in FY21, impacted by a 66 percent year-on-year decline in passenger traffic.

Jet Airways, which will now be headquartered in Delhi NCR instead of Mumbai, will start with leased narrow-bodied aircraft. It has already hired over 150 full-time employees and will add another 1,000 over the next few months.

The Jalan-Kalrock resolution plan had been approved by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) on June 22. The Mumbai bench of the NCLT had given the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) and the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) 90 days from June 22 to allot slots to Jet Airways. The Jalan Kalrock Consortium has agreed to make a total cash infusion of Rs 1,375 crore in Jet Airways, including Rs 475 crore that will be used for payment to stakeholders and creditors.

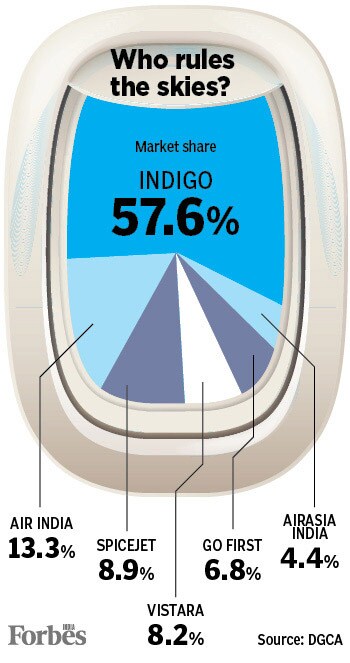

In the skies, Jet Airways is likely to face some serious competition, something that had led to its downfall over the years. For instance, market leader IndiGo continues to cement its place in the aviation industry with a near-60 percent market share. Over the third week of September, in what’s seen as an indicator of investor confidence in the airlines, the shares of InterGlobe Aviation, Indigo’s parent company, surged by 14 percent, touching a fresh 52-week high.

SpiceJet, India’s second-largest private airline, had also surged by 17 percent in the same week. On September 20, the government permitted airlines to operate a maximum of 85 percent of their pre-Covid domestic flights, instead of the 72.5 percent allowed since August 12. Between July 5 and August 12, the cap stood at 65 percent. Between June 1 and July 5, the cap was at 50 percent.

Then there is the new entrant that will take to the Indian skies: Akasa Airlines, led by Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, which plans to launch an ultra-low-cost carrier (ULCC) next year. MoCA and DGCA awarded a no-objection certificate to Akasa this August.

A ULCC, unlike a low-cost carrier, operates with unbundled fares, making it cheaper for customers. This means that apart from the seat, all other amenities such as baggage, seat preference, or food are subject to additional fees. ULCCs usually have fewer amenities than low-cost carriers, which provides a bigger revenue source from ancillary services for airline operators.

“Typically, you need people, machines, and money to get an airline into the skies," says Jitender Bhargava, a former executive director of Air India. “There is very little known about Jet Airways’s plans, whereas other entrants such as Akasa have clear plans. They have a team in place, including veterans of the Indian skies. But, as far as Jet Airways goes, the promoters have very little experience in running an airline."

“For an airline to take off, you need an air operator certificate [AOC], which is linked to the aircraft type," says Satyendra Pandey, partner at advisory firm AT-TV and former head of strategy at GoAir. “While procuring an aircraft may not be an issue, other factors like pilots, routes, slots, and training will take time. Jet will need to sell inventory one or two months in advance, which makes their plan quite ambitious. Nobody really knows the plan going forward."

Akasa is in talks to add 100 new Boeing 737 Max aircraft to its fleet. It has also recruited the likes of former Jet Airways CEO Vinay Dube, GoAir’s former chief commercial officer Praveen Iyer, and the former head of treasury and investor relations at IndiGo Ankur Goel. “I’m very, very bullish on India’s aviation sector in terms of demand," Jhunjhunwala had told Bloomberg in July.

Lot of churn

Either SpiceJet or the Tata Group is likely to take control of India’s flagship carrier, Air India, and set itself on a path of aggressive transformation, which means the competition in the space is only likely to intensify. “Financial bids for Air India’s divestment were received by the Transaction Adviser. The process now moves to the concluding stage," Said Tuhin Pandey, secretary for the department of investment and public asset management, on September 15.

“Ideally, the transaction will go through successfully, but the government should not be left scrambling for answers at the time should that not be the case," said Capa in its report. “Closing Air India would not only be extremely challenging politically but will have a notable impact on the market, especially in the international segment."

![]()

Ajay Singh, the founder of SpiceJet, has reportedly managed a bank guarantee from State Bank of India (SBI) to make the bids, even though his airline has seen its net worth erode over the past few years. For the fiscal ended 2021, SpiceJet’s losses stood at Rs 998 crore. Since then, the airline has made losses every quarter, including a loss of Rs 729 crore in the April-June quarter. Rival IndiGo’s case isn’t any different. It has seen losses rise to Rs 5,829 crore, although it has higher cash reserves and plans to raise Rs3,000 crore from qualified investors, in addition to another Rs4,500 crore through bank credit lines and sale-and-leaseback deals with lessors.

“The combined Air India-Tata entity will be very strong in the international market, while IndiGo continues to cement its place in the domestic skies," Bhargava says.

Then there is a plan by Go First, formerly GoAir, to put itself on a path of growth by following the ULCC model after many years of struggle. Over the next two years, the airline wants to corner 20 percent of the domestic market, and increase its fleet to 87 aircraft by 2023, from the current 55. It operates Airbus A320 Neos and is expected to add over 78 aircraft after 2023.

Helming that transition is Ben Baldanza, who has taken charge as vice chairman. He is a pioneer in the ULCC model, having served as CEO of US-based Spirit Airlines for over a decade. Baldanza also has Kaushik Khona, a long-time veteran of the Wadia Group (promoters of Go First), who has returned to Go First after leaving as its CEO in 2011. Baldanza has been part of the airline’s board since 2018 and has a reputation for transforming Spirit into North America’s first ULCC, with cheap fares and high-profit margins. During his tenure, Spirit increased its fleet from 32 to 100. Markets regulator Sebi has given the green signal to Go First’s planned maiden public issue of shares it had earlier suspended the initial public offering (IPO) of GoAir.

“We continue to believe there will be strategic consolidation in the Indian airline sector once the Covid-19 umbrella has lifted," the Capa outlook says. “If there is no consolidation [although such a scenario appears unlikely] and if the privatisation of Air India does not proceed, then the Indian aviation sector may emerge from Covid-19 with more airlines than it went in with, as it is possible that 1-2 startups may launch, resulting in 8-9 carriers in total. Under other scenarios, we could be left with just 3-4 carriers. Every airline’s business case will be impacted by the different competitive dynamics under each of these diverse scenarios. The next few months will be key to determining the long-term outlook."

There are logistical challenges too. Aviation turbine fuel (ATF) prices have risen by over 30 percent since the beginning of 2021, and accounts for nearly 40 percent of the cost of running an airline in India. Globally, the aviation industry has incurred losses of $371 billion in revenues in 2020 and is expected to post between $296-317 billion in losses during 2021.

The paradox doesn’t stop with airlines. On July 13, less than a year after it forayed into India’s lucrative airport sector, the 32-year-old Adani Group became India’s largest airport infrastructure company, its airports seeing one in every four passengers passing through them, and accounting for one-third of India’s air cargo.

The steady climb to the top has come after the group took control of the Mumbai airport. Through its subsidiary Adani Airport Holdings Ltd (AAHL), it acquired a 50.5 percent stake in Mumbai International Airport Ltd (MIAL) last year from Hyderabad-based GVK group.

AAHL acquired another 23.5 percent stake this February for Rs 1,685 crore from the two foreign partners—Airport Company of South Africa and Bidvest—in MIAL, increasing its stake to 74 percent. The government-owned Airports Authority of India (AAI) holds the remaining 26 percent in MIAL. “As the economy normalises, revenues are expected to grow with the business, and international travel will accelerate as the world and India emerge from the pandemic," said Malay Mahadevia, CEO of AAHL, to Forbes India in July.

So where does Indian aviation go from here? “Given the resurgence of the second wave of the pandemic, the recovery in passenger traffic will only be gradual, with the domestic passenger traffic expected to reach pre-Covid levels only by FY24," says Kinjal Shah, vice president and co-group head at rating agency ICRA in a recent report. “Limited elevated ATF prices and fare caps continue to pose a challenge for the profitability of the airlines. Thus, the Indian aviation industry is expected to report a net loss of Rs 250 to Rs 260 billion (Rs 25,000 crore to Rs 26,000 crore) in FY22."

Indian aviation: A renewed fight for the skies. Representational Image (Shutterstock)

Indian aviation: A renewed fight for the skies. Representational Image (Shutterstock)