Unsung heroes: NGOs, community, people

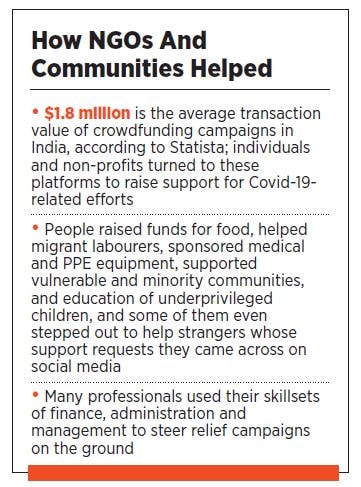

Non-profit organisations, individuals and community initiatives chipped in to work on the ground, and combat the social and economic fallouts of the pandemic

Khaana Chahiye, a citizen-led movement now registered as an NGO, served around 47 lakh meals and 20,000 ration kits to migrant workers and slum dwellers around Mumbai

Khaana Chahiye, a citizen-led movement now registered as an NGO, served around 47 lakh meals and 20,000 ration kits to migrant workers and slum dwellers around Mumbai

Image: Mexy Xavier[br]In March, when migrant workers from Mumbai started walking long distances to reach home, and many impoverished slum areas in the city were unable to access food due to the pandemic restrictions, seven people from different career backgrounds in Mumbai decided to join hands to launch a citizen-led initiative to combat hunger. They mapped out different clusters or arterial roads in the city where they could distribute biscuit-and-food packets, identified restaurants that could turn into community kitchens, and also turned to social media to find volunteers who would help scale up their efforts.

They called the initiative Khaana Chahiye, and to date, have distributed 47 lakh meals, 20,000 ration kits and reached out to about five lakh migrant workers. During the peak of the lockdown months, the team was serving at least 70,000 meals on a daily basis. “In March, we started with a pilot of distributing 1,200 meals across the Western Express Highway, and soon expanded operations to arterial stretches like SV Road, Link Road, Eastern Express Highway and LBS Marg,” says Ruben Mascarenhas, an activist who leads a community collective of changemakers at the Litmus Test Project.

Other co-founders of Khaana Chahiye include restaurateur Neeti Goel, Shishir Joshi of volunteer-led organisation Project Mumbai, businessman Anik Gadia, digital marketer Swaraj Shetty, advocate Rakesh Singh of grassroots non-profit Bharat Utthan Sangh, and software consultant Pathik Muni. “We also reached out for more volunteers on social media and through word-of-mouth, and we got as many as 400 people who responded and wanted to contribute,” Mascarenhas says.

This team of volunteers included IT and finance professionals, CXOs, actors, marketing professionals, musicians, students and chefs. The initiative put their skillsets to use to manage tasks, including kitchen hygiene and quality, supply chain management, fundraising, accounting, finance and volunteer management. Around 200 of these volunteers continue to actively work for the initiative even today.

Given the sustained response to the initiative, the co-founders of Khaana Chahiye decided in November to transform the movement into a registered foundation that could tackle the issue of hunger post-Covid too.

This meant building a digital hunger map of the city that would “map micro-clusters of vulnerable slums and homeless people,” adds Mascarenhas, who is also the national joint secretary of the Aam Aadmi Party. “We collect data on our app during our weekly drives and upload it on the map. We hope this will help us identify consumption patterns so that we can connect these people to public distribution systems and government schemes, which is a more long-term, sustainable approach to help them get regular access to food.” Khaana Chahiye also managed to raise ₹1 crore through crowdfunding and an additional support of ₹12 crore from partners and corporates.

During the course of the lockdown and after that, many individuals stepped up to help others in a personal capacity. For example, Bengaluru-based digital marketer Mahita Nagaraj managed to fulfil more than 26,000 requests for help and support through her Facebook group Caremongers India. There was also businessman Maurius Norohna from Mumbai, who spent over ₹1 crore that he was saving for immigrating to the US, to provide groceries and food supplies to lakhs of people around his Borivali locality. He also distributed medical supplies and sponsored ambulances across Maharashtra.

Crowdfunding also emerged as a way for common citizens to contribute towards Covid-19 relief efforts. According to Mayukh Choudhury, co-founder of crowdfunding platform Milaap, “Over 272,656 donors came forward to help. More than 12,600 fundraisers were set up for Covid-19 relief by individuals and organisations alike, where people generously contributed over ₹12 crore.” People contributed toward raising money for food, medical and PPE equipment, and helping vulnerable people.For example, in the coastal town of Cuddalore in Tamil Nadu, Kanavu, an initiative working with non-profit Association for Sarva Seva Farms (ASSEFA), crowdsourced close to ₹15 lakh to help 1,200 children to continue education. “Most members of the community are daily wage earners or landless labourers, so the pandemic created various issues of survival for them,” says Gowtham Reddy, who co-founded Kanavu in 2017. “In the five low-income private schools that we work with, salaries of the 50 teachers and five headmistresses depend on the fees paid by parents. During the pandemic, it became impossible for parents to pay. And the children lagged behind their grade levels because they were not able to receive sustained formal education.”

Before they tackled the issue of poor internet connectivity, the team at Kanavu had to first ensure sufficient food was available for these children and their families. With the help of the Wipro Foundation, they distributed dry rations to families across the five schools for three weeks. During this process, they also collected data on the financial and employment status of each family, along with availability of internet and smartphones for the children to continue studies.

“We realised that about 45 percent of parents had smartphones and internet connectivity, but 55 percent did not have any access. Many teachers also had only feature phones,” Reddy says. So the team, with the donations they had received, procured second-hand digital devices. They also trained teachers on how to effectively use these platforms. For kindergarten children, digital study material was sent to parents for homeschooling.

Even with internet connectivity, parents and teachers could not afford to be on data-guzzling platforms like Zoom and Hangouts, so Kanavu created study materials on YouTube and used WhatsApp for communicating and conducting practice tests and homework. “It’s not education as usual, and we are working toward helping every individual kid receive the extent of support and hand-holding they need.”

First Published: Jan 14, 2021, 09:46

Subscribe Now