Saving artists' legacies by preserving their studios

Studios, tools, letters and belongings tell you as much about artists as their artworks

The room was barren, its floor spotlessly clean. There was no furniture in it, except for an architect’s drafting table, sitting beneath a single low-hanging bulb, in the middle of the room. She sat at the table, like a meditating monk at night time her hands, which would otherwise involuntarily tremble because of a neurological disorder, were unwavering and steady. You could feel the room fill with the vibrations of her presence… and the voice of Bhimsen Joshi.

“People must know that her art and her space were inseparable,” says Roobina Karode, of Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990), while describing an exhibit she had curated in 2013 for an exhibition called ‘A view to infinity NASREEN MOHAMEDI: A retrospective’ at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) in New Delhi, depicting the studio in which Mohamedi worked.

Mohamedi, who did not receive much recognition in her lifetime, is now considered one of the most significant Indian artists within the modernist tradition, with her work receiving international critical acclaim only in recent years. “The studios of most artists are messy. But Nasreen’s studio in Baroda was impeccably clean and uncluttered. There were no distractions. The space had a very restorative feeling,” says Karode, director of KNMA.

This intimate space in which Karode had found herself as a 16-year-old student with Mohamedi left such a lasting impact on her impression and knowledge of the artist that she felt an exhibition of Mohamedi’s creations would not be complete if visitors could not see and feel the space and ambience in which she had worked.

That an artist’s tools are extensions of her hands, and the studio an extension of her being, is something Karode firmly believes in. This is the guiding force behind an exhibition that she is curating on Himmat Shah, scheduled to be on display at the KNMA in January 2016. Shah, a sculptor, now 82, works with a variety of material including plaster, ceramics and terracotta. “He is a recluse, but his studio in Jaipur is fascinating,” says Karode. “In between all the terracotta heads that he creates, you can see the tools that he works with he has made some of these himself. They are like cookie cutters, or a carpenter’s tools. You cannot think of an artist without thinking of his tools.”

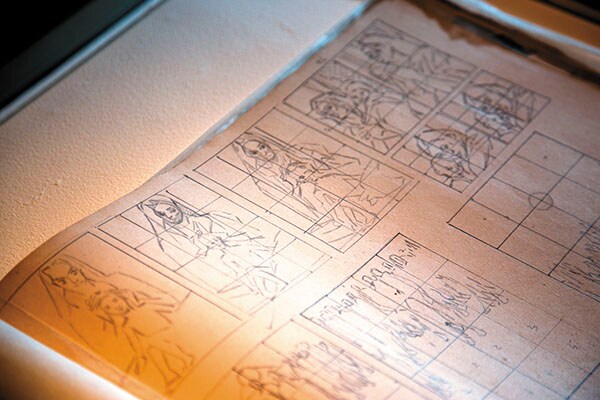

It is, however, rare for the tools and working spaces of artists in India to be preserved for posterity. Given that many artists work within their homes, it is often the families who find themselves as the custodians of these belongings.  Image: Joshua Navalkar

Image: Joshua Navalkar

Initial drawings of a painting, form part of the Jehangir Sabavala bequest at the CSMVS in Mumbai

Such has been the case with the personal archive of Jehangir Sabavala (1922-2011), one of India’s best-known modern artists. An exhibition called Unpacking the Studio: Celebrating the Jehangir Sabavala Bequest opened at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) in Mumbai on September 15 and showcased 140 items that belonged to Sabavala, which had so far been with his wife Shirin. These belongings have now been donated to the museum.

“It is perhaps for the first time in the history of Indian museums that a personal archive has been donated to a public museum,” says Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director, CSMVS. “A studio gives an overview of an artist’s growth. It is a part of our modern and contemporary history.” The bequest by Shirin Sabavala comprises her husband’s last paintings, a rich archive of the artist’s papers, photographs, books, portfolios of drawings and sketchbooks. Some of these date back to the 1940s, when he was a student.

The studio was a very special space for him,” says Ranjit Hoskote, curator of the exhibition at CSMVS and someone who had known the artist for many years. “This exhibition takes a very private space and recreates it in a public space.” The process of curating the exhibition, he admits, was a deeply emotional one for, while one part of him wanted to protect the privacy and intimacy of Sabavala’s studio, the curator in him wanted to share it for the purpose of historical narrative.

The exhibition—which also comprises works by Sabavala from CSMVS’s collection—had two objectives, says Hoskote: First was to celebrate the bequest, which is a huge archive and the second was to display Sabavala’s works in context. So, not only do you get to see a recreation of Sabavala’s studio, with his easel, his brushes and his palettes, you also get to appreciate the manner in which his work evolved over the decades and the influences that find reflection on his canvases.

“It is something very rare,” says Hoskote, “for a family to donate items and paintings like these. You can imagine how much these paintings would now be worth. But Jehangir always wanted these things to go to the city, to the people of the city.” Sabavala’s mother, Bapsy, belonged to the affluent and aristocratic Cowasjee Jehangir family, which was responsible for building some of the biggest and best-known institutions in Mumbai, including the Gothic structure that houses the Elphinstone College and the Mumbai University’s Convocation Hall. Philanthropy has had a long-standing position within the family.

The preservation, documentation and archiving of personal belongings do not follow a fixed pattern. Different methods and routes have been adopted, although with similar goals in mind. A bequest like Sabavala’s is very different from, say, the belongings of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore that are archived at Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, the university which he founded in 1921, and where he lived for many years, and at his ancestral home in Jorasanko, Kolkata.

Rabindra Bhavana, the museum at the university, was established in 1942, a year after Tagore’s death, with the intention of preserving several hundred of his manuscripts in Bengali and English, hundreds of correspondence, books, paint brushes and sketches for posterity and also for the purpose of research. Rabindra Bhavana also houses Tagore’s personal library and various objects used by him, his voice-recordings and thousands of photographs taken of him at different times and places, along with the many gifts, honours and addresses which he received from different parts of the world.

At the Uttarayan Complex of the university, the five homes in which Tagore lived at some point of time or the other have been kept in their original form. “Some of these have furniture from the years of his stay here, along with photographs. Although the rooms are kept in their original form, the furniture is rearranged sometimes,” says Anshuman Dasgupta, assistant professor II at Visva-Bharati University. “While more of his paintings are kept at the archives in Santiniketan, there are more personal belongings that are kept at Jorasanko.” The architecture of the houses, their interior decoration and the furniture strewn about the rooms bring to life Tagore’s persona. This unit of Rabindra Bhavana has more than 1,500 original paintings by Tagore and more than 500 by others, a curio collection of over 3,800 items, along with 52 statues.

Sometimes, it is not just the studios and working tools of artists that draw the attention of archivists and researchers. Personal living spaces, everyday objects of use and correspondence, too, provide significant insight into not just the minds and lives of the artists, but also the times in which they lived and worked.

Shilpa Gupta’s work ‘The Photo We Never Got’ at the India Art Fair in 2015 (top left and top right) maps relationships within the art community through personal memorabilia ‘Another Life’, at the Hong Kong Art Fair in 2011 (bottom right and bottom left), was a recreation of the home library of art critic Geeta Kapur and installation artist Vivan Sundaram

Shilpa Gupta’s work ‘The Photo We Never Got’ at the India Art Fair in 2015 (top left and top right) maps relationships within the art community through personal memorabilia ‘Another Life’, at the Hong Kong Art Fair in 2011 (bottom right and bottom left), was a recreation of the home library of art critic Geeta Kapur and installation artist Vivan Sundaram

And this is what the Asia Art Archive (AAA) strives to do. With an aim to digitise and document the works and personal belongings of artists, AAA is making these materials available on its website for anyone curious enough to want a peek into the life and times of different artists. Formed in Hong Kong in 2000, AAA started work in India in 2007 by collecting archival material and documents.

In 2010, they began digitising the personal archives of art critic and curator Geeta Kapur and her husband and contemporary artist Vivan Sundaram. “This was the first personal archive that we digitised,” says Sabih Ahmed, senior researcher at AAA. “The process is one that takes place through extensive dialogues with the artists to decide and select what will be digitised and archived. They also get a copy of the digitised work.” Work on Kapur’s and Sundaram’s archives took a year to finish. However, the project did not end with digitisaion alone. To represent the archive in a spatial form, AAA set up ‘Another Life: The Digitised Personal Archive of Geeta Kapur and Vivan Sundaram’ at the Hong Kong Art Fair in 2011, in which they recreated Kapur’s and Sundaram’s home library, a microcosm of the world in which they worked. “They gave us their furniture, books and albums to carry to Hong Kong,” recalls Ahmed. “It was a very idiosyncratic space, with very different textures. Vivan is an installation artist and does not work in a specific artist studio.”

The dimensions of the recreated home library were not identical to the original space, but “we took these hi-res photographs of their walls, the shelves on their walls, which were packed with books, and printed them to scale,” says Ahmed.

This meant that visitors could actually see each and every item kept on the shelves, as they would have had the real shelf been before them. “We even got Geeta’s pinboard with the postcards that she had pinned on to it.” Through the scaled photographs, books, image projections, video footage, music and even scent, the exhibit recreated the physical archive of these two significant figures in Indian art history.

AAA has also digitised the personal archives of artists Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, Jyoti Bhatt, KG Subramanyan and Ratan Parimoo, one of the first generation of teachers at the MS University in Baroda. The project, that started in 2011, took two years to complete. “We chose these four faculty members not only because we wanted to archive their personal careers, but also the contribution they have made to the field of art and to get a holistic view of their times,” says Ahmed.

But deciding on what to archive (or put up on public display) is a tricky path to walk on. For, the personal lives of many artists are intricately intertwined with their creative processes and works. Not only are their styles and subject matter influenced by their personal circumstances and relationships, where and how they work is also often determined by factors such as moving to a new place to be with their partners. “We had invited Shilpa Gupta to work on the archival material before the 2015 India Art Fair, and she commented that there were no love letters among all the archival material,” says Ahmed. Consequently, Gupta wanted to focus on relationships, love stories, friendships, marriages and fallouts. Human relationships, too, shape the field of art as much as any other influence.

‘The Photo We Never Got’, the exhibit that Gupta created out of numerous letters, photographs and other memorabilia, is like going back in time and joining the dots between events, meetings, conversations and correspondence that were merely a part of the artists’ lives, but which also, indelibly, have formed the narrative of art history of that period.

“An object of art does not exist in vacuum. Artists float in this loose community that has an effect on their artworks,” says Gupta, whose intention was to relook at art history narrative, which has traditionally focussed on just the artworks.

Constructed from material painstakingly acquired from artists—“most of the process comprises talking to artists they are very happy actually to talk about the past”—the exhibit, for instance, has a photograph showing a group of artists protesting in front of the Lalit Kala Akademi, and then, in another photograph, the same artists are chatting with writer Mulk Raj Anand, who was part of the Akademi, and discussing an oncoming exhibition. The photographs show how the same group of people had relationships at different levels with each other, says Gupta. “They are very layered relationships.” There are instances too of artists becoming the subject of an artwork for instance, photographs of a group out on an excursion. “You can see them in their sunglasses, and against the backdrop of the outdoors, of trees. They are just having a good time,” says Gupta.

Amrita Sher-Gil’s correspondence in the 1930s with Ram Chandra Tandan, who was the secretary of the Hindustani Academy in Allahabad, for instance, gives a glimpse into the organisation of an exhibition of her artworks in Allahabad in February 1937, and the printing of a catalogue of her works.

These letters, which were in the possession of the Tandan family, were recently auctioned by Saffronart in Mumbai. [The Tandan family had earlier (in 2009) auctioned correspondence that belonged to Nicholas Roerich, including a letter from Albert Einstein to Herrn Arnold Schwarz about the Roerich Museum in 1931, passports, visas and permits to travel in different countries, letters and documents of awards and citations, as well as exhibition catalogues.]  It gives a glimpse of the artist’s personal life, including his happiness when his proposal for marriage was accepted by Barbara Zinkat

It gives a glimpse of the artist’s personal life, including his happiness when his proposal for marriage was accepted by Barbara Zinkat

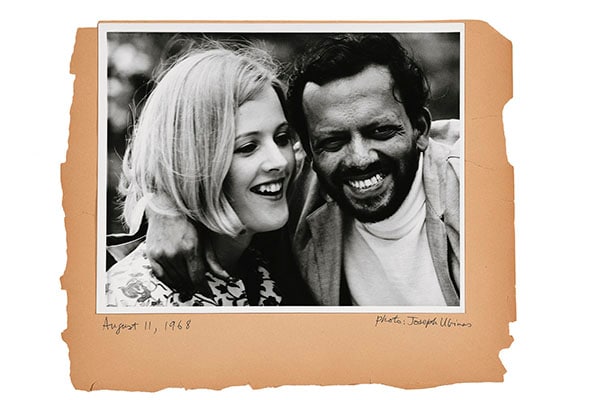

Saffronart also recently auctioned personal photographs and memorabilia of FN Souza, a founding member of the Progressive Artist’s Movement—three pages from Souza’s scrapbook is a peek into the artist’s private world, for instance, his excitement when his marriage proposal is accepted by Barbara Zinkat in 1964.

The Sabavala exhibition at CSMVS has as its first chapter a section titled ‘Imagination’s Chamber’ that explores the evolution of the artist’s studio, as it assumed many avatars over the centuries. The chapter is a visual history of the studio’s evolution from the period of the Northern Renaissance to the present, beginning with the workshop or bottega, transforming into a retreat of studiolo, an atelier, a laboratory, a performance venue or an outdoor site.

As the evolution of the artist’s workspace has evolved, reflecting changing circumstances and practices, the process and methods of preserving and archiving these spaces and tools too shed light on contemporary times. “Artists in the 19th century had their ateliers,” says Ahmed. “The ones in the 20th century had their studios. And now you have video and installation artists.” How would the archival material of these artists be preserved? How would email correspondences and JPG attachments be documented?

If art and artists have found their way, archivists will too.

First Published: Feb 27, 2016, 06:05

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Oct 08, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)