Mainstream Hindi cinema is easy on our conscience. We know who the good guys are, who the bad guys are, who we should root for, and who needs to die in the end (unless the cops turn up and play spoilsport).

Also, in the world of Hindi cinema, villainy often has a kind of magnetism that heroism rarely has: Villains come wrapped in an abundance of charm, confidence, cunning and control that heroes (female ones included) barely possess. In scene after scene, movie after movie, heroes bluster on with lines of heavy dialogue, while the villains sedately smoke cigars, or nod indulgently with amused smirks on their lips heroes blunder their way through the plot, falling prey to temptations and travails, while villains remain steadfast in their ideals and objectives. If the hero manages to finally prevail over the villain—often with the help of generous amounts of luck and chance—it is almost always because good must prevail over evil (audiences don’t take too well to cynical plotlines), and not really because the villain comes up short. We are all too aware that villains are perhaps better than the heroes in every which way, except in that sticky department of morals.

METHODOLOGY: How we crunch the numbers

PHOTO GALLERY: Top 10 celebs in 2016 Forbes India Celebrity 100 list

PODCAST: The cerebral side of 2016 Forbes India Celebrity 100 list

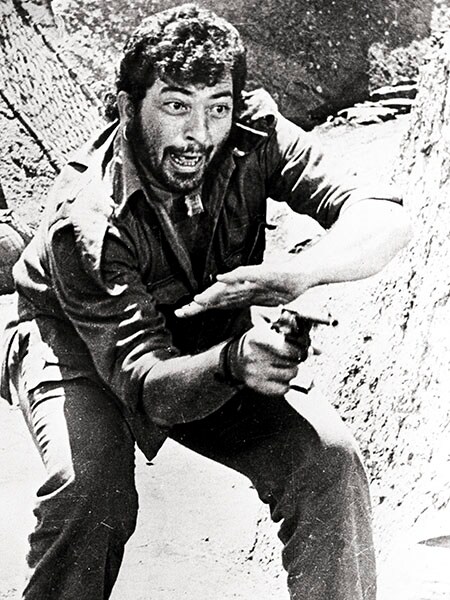

Morals were what separated the good from the bad. And the lines were clearly demarcated among actors and even at award ceremonies. Indian film awards follow this strict demarcation by having separate categories for actors in ‘a negative role’, unlike, say, the Oscars or the Baftas, which have no such category. It is almost as if we are morally obligated not to award a villain the award for the best actor. Or is it because we know who the better actor really is?![mg_91443_amjad_khan_280x210.jpg mg_91443_amjad_khan_280x210.jpg]()

Amjad Khan in the iconic role of Gabbar Singh in Sholay

Image: Express Archive PhotoFrom the 1950s to the 1990s, villainy lay in the clutches of a few actors—Pran, Premnath, Ajit, Prem Chopra, Ranjeet, Amjad Khan, Amrish Puri, Gulshan Grover, Shakti Kapoor, and Kiran Kumar are some of the most prominent ones. While it was not entirely unusual for these actors to portray non-villainous characters—Pran being the most prolific in this category with roles such as Sher Khan in Zanjeer, Michael Gonsalvez in Majboor and Jasjit in Don—it was unthinkable that an actor who played the hero would take on a negative role. Even when heroes crossed over to the dark side—Amitabh Bachchan, most notably, in Deewaar or Kaalia—they did so for the sake of their families, which automatically justified all their crimes in the eyes of the audience alternatively, they started out as baddies, and eventually grew a heart of gold.

And then along came the upstart called Shah Rukh Khan in 1994 when the hero himself morphed into the villain, breaking an age-old taboo in the world of Hindi cinema.(But more on that later.)

***

Though there have been villains of varying kinds, it would not be entirely inaccurate to claim that the myriad faces of the Hindi cinema villain are representative of their times. At different points in time, different groups of people have been considered ‘bad’ by society, giving rise to discernible patterns in the way villainy has been portrayed on screen.

In the 1950s, while India grappled with land reforms and the abolition of the zamindari system, villainy came in the shape of the landlord. Long vilified in Indian literature as the embodiment of all things oppressive, unjust and evil, the zamindar—and all its variants, such as kunwar saab, raja saab, rai saab, raja thakur, etcetera—was a character that was easily identifiable.

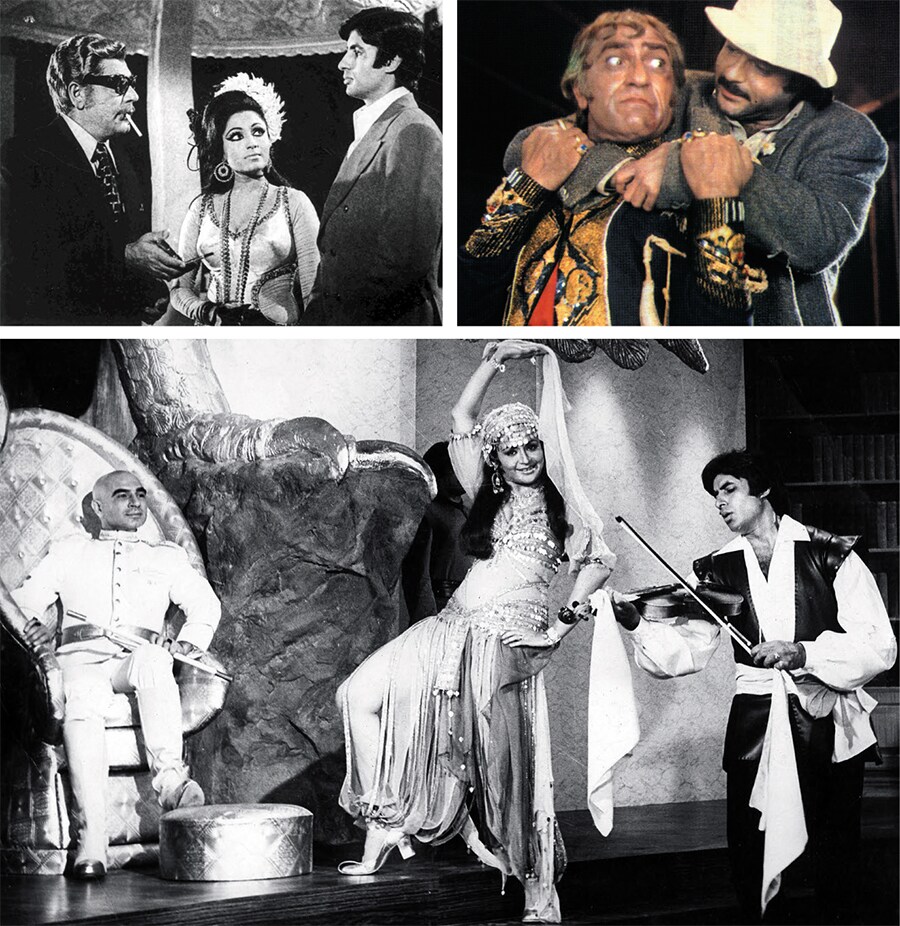

An early example of this is the character of Thakur Harnam Singh in Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953). Insecure, greedy and manipulative, he brings ruin upon the farmers who till his land (by planning to build a mill on it), and in particular to the family of Shambhu Mahato, immortalised by Balraj Sahni. But while Harnam Singh portrayed a middle-aged landlord facing uncertainty in the face of land reforms, Ughranarayan from Bimal Roy’s Madhumati (1958) had no such compulsions. Portrayed by a suave and dandy Pran, Ughranarayan is the quintessential young, absentee landlord who rules by the lash of his whip. Dressed in riding breeches and knee-high boots, or ornate dressing gowns, he towers over Dilip Kumar’s righteous and soft-spoken Anand.![mg_91445_villians_280x210.jpg mg_91445_villians_280x210.jpg]() (Clockwise from top left) Ajit (left) plays gang leader Teja in Zanjeer Amrish Puri (left)as Mogambo in Mr India Kulbhushan Kharbanda (left) as Shakaal, the sadist crime lord, in Shaan

(Clockwise from top left) Ajit (left) plays gang leader Teja in Zanjeer Amrish Puri (left)as Mogambo in Mr India Kulbhushan Kharbanda (left) as Shakaal, the sadist crime lord, in Shaan

Image: Express Archive Photo

One of the incarnations of the tyrannical landlord was the oppressive moneylender. A fixture in the fabric of rural India, this was another character that easily lent itself to villainy. For instance, Sukhilala in Mother India (1957) is the cause of all misery in the lives of Radha (Nargis) and her sons Birju (Sunil Dutt) and Rama (Rajendra Kumar). So death-like was the grip of account books on the lives of farmers that Birju, in his ultimate act of revenge, hurls Sukhilala’s ledgers into a blazing fire.

The feudal hangover continued well into the 1960s in mainstream and well into the 1980s in parallel cinema, with the scheming and unscrupulous characters of Kunwar Saab in Teesri Manzil (1966) and Ranjit (alias Bhupender Singh) in Johny Mera Naam (1970), portrayed by Premnath. Both characters belonged to the rich and landed aristocracy—they were impeccably dressed and lived the good life while being corrupt and ruthless in their ways. Meanwhile, in parallel cinema, Sajal Roy Choudhury, for instance, played the greedy moneylender in Mrinal Sen’s Mrigayaa (1976), Mithun Chakraborty’s debut film, while Naseeruddin Shah played the arrogant subedar in Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala (1987).

***

By the mid-1970s, the landlord was no longer fashionable in mainstream Hindi cinema as the realities of independent India changed rapidly. Moving on from the vestiges of a colonial past, villainy now came in the form of those who broke the law of the land. And who could break it with as much frequency and panache as Bombay’s ganglords and smugglers? Following the ban on gold imports post-independence, gold was (and continues to be) one of the most coveted commodities smuggled into the country. Thus emerged characters such as Teja (Zanjeer, 1973), Shakaal (Yaadon ki Baaraat, 1973) and Deen Dayal, better known as ‘Loin’ (Kalicharan, 1976), played by Ajit. They were rich and flamboyant characters who ran crime networks, employed tough-looking henchmen, had female arm candies, and paid off corrupt policemen.

While in the badlands of Bombay, mention must also be made of the exploitative owners of mills, factories and businesses in a way, they were the modern-day versions of the landlords and moneylenders. Although these characters did not often occupy much screen time or space, they created the socio-economic background against which the hero rebelled. Instances of this have been seen in Namak Haraam (1973), Deewaar (1975), Trishul (1978), Kaalia (1981) and Laawaris (1981).![mg_91447_sunjay_dutta_280x210.jpg mg_91447_sunjay_dutta_280x210.jpg]() (Clockwise from left) Karan Johar"s 2012 Agneepath saw Rishi Kapoor and Sanjay Dutt don menacing new avatars Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Gangs of Wasseypur II

(Clockwise from left) Karan Johar"s 2012 Agneepath saw Rishi Kapoor and Sanjay Dutt don menacing new avatars Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Gangs of Wasseypur II

However, the villain who stood head-and-shoulders above all the rich, urbane, and flamboyant bad men of the 1970s was, of course, the tobacco-chewing, rotting-toothed, trigger-happy, rustic Gabbar Singh of Sholay (1975). Hindi cinema had seen dacoits before—from Pran in Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai (1960) to Prem Chopra in Mera Saaya (1966)—but none came close to the undiluted evil of Gabbar. Unlike the dacoits of past films, Gabbar did not abide by any honour-among-thieves rulebook, and killed his own men with as much glee as he killed hapless villagers.

The flamboyance of the 1970s went haywire in the following decade with villains who verged on the ludicrous with their appearances and manic idiosyncrasies. Heralding this era was Shakaal, played by Kulbhushan Kharbanda in Shaan (1980), a film that was clearly inspired by the James Bond franchise in more ways than one. From Usha Uthup’s throaty title song to Kharbanda’s Yul Brynner-esque bald pate and pet sharks in giant fish tanks, it was the film that took villainy into almost something akin to lunacy. Following in these footsteps were characters like Dr Dang, played by Anupam Kher, in Karma (1986) and, of course, Mogambo, played by Amrish Puri, in Mr India (1987). Not content any longer to run smuggling networks, villains like Dang and Mogambo went many steps ahead of Shakaal with their goals to control and conquer the whole country.

These characters, although memorable, were shortlived, and Hindi films soon fell back on the tried-and-tested characters of ganglords, smugglers and bootleggers. This is the period that saw the emergence of characters such as Lotiya Pathan, played by Kiran Kumar, in Tezaab (1988), Kancha Cheena, played by Danny Denzongpa, in Agneepath (1990), and Maharani, chillingly played by Sadashiv Amrapurkar, in Sadak (1991). The ganglords, too, refused to remain confined to India’s physical boundaries and began to expand their horizons—like Ajgar Juraat, played by Amrish Puri, in Vishwatma (1992), and Pasha, played by Kiran Kumar, in Khuda Gawah (1992). The one villain of the 1980s that broke the mould and created a new genre of movie-making in India was that of Anna, played by Nana Patekar, in Parinda (1989). Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s second feature film brought the ganglord down from the high echelons of style and panache, and nailed him for good to the ground of reality. Gone were the urbane clothes and homes, the nightclubs and female arm candies, the stylishly-dressed henchmen and fancy cars. What emerged was an underworld don with a brooding, impenetrable face, a sharp streak of lunacy, and a deep fear of fire. Where Teja and Loin had amused the audience with their heavy dialogues, Anna sent a cold shiver down their spine with his manic laughter.

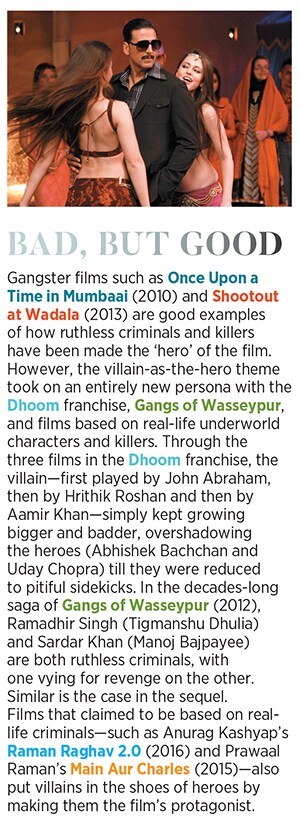

Although Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998) is often hailed as the first film that portrayed Bombay’s crime world in a realistic manner, it was Parinda that had taken the first step in that direction. What Varma succeeded in doing—through his many films about the city’s underworld—was to create a hero out of the ruthless ganglord the hero who was no longer shackled by issues of morality and ethics, criminality and corruption a hero who was as bad, if not worse, as all the villains of yesteryears in his actions and thoughts, but remained a hero by virtue of being the protagonist. The villain-as-the-hero theme has been amply explored in films such as Company (2002), where Ajay Devgn plays a gangleader called Malik, Sarkar (2005), where Amitabh Bachchan plays a Vito Corleone-like character called Subhash Nagre, and Gangs of Wasseypur parts 1 and 2, where Manoj Bajpai and Nawazuddin Siddiqui play criminals in the coal belts near Dhanbad. (See box.)

***![mg_91449_akshay_kumar_280x210.jpg mg_91449_akshay_kumar_280x210.jpg]()

In 1993 was born a villain who did not have a fiefdom to rule over, a list of criminal activities and imprisonments to boast of, or personal grievances to avenge. He was simply obsessed with a woman. When Shah Rukh Khan appeared as Rahul in Darr (1993), he did what no other actor before him had done: Switch from being the ‘good guy’ to becoming the undisputed ‘bad guy’. While in Baazigar (1993), too, he played what was touted as the ‘anti-hero’, it could still be argued that his character, Ajay Sharma, was seeking revenge against Madan Chopra (Dalip Tahil), who had wrecked Ajay’s father’s business empire—a much-beaten plot in Hindi cinema. In Darr, however, there was no such justification. Rahul was simply obsessive, scheming, violent and murderous.

Although the immense hype generated at that time around the concept of ‘anti-hero’ was to promote the film, the publicity was perhaps unintentionally prophetic. For what followed were several films where actors who had so far played heroes (and heroines) began to portray negative characters. Cases in point are Kajol playing the obsessed and murderous lover in Gupt (1997), Urmila Matondkar playing the psychopathic killer on the loose in Kaun (1999), Amitabh Bachchan playing the shapeshifting killer in Aks (2001) and a vengeful bank manager in Aankhen (2002), Ajay Devgn playing a criminal ringleader in Khakee (2004), and Saif Ali Khan playing the scheming and manipulative underworld operative in Ek Hasina Thi (2004).

Although this could have been just a passing trend that was cashing in on the cult of the anti-hero, it proved to be more lasting than that. What this trend effectively did was erase the line that had so long separated actors into two broad categories: Those who played positive roles, and those who played negative roles. Although there are examples such as Arjun Rampal playing the namesake villain in Ra.One (2011), and Vivek Oberoi playing Kaal in Krrish 3 (2013), it was producer Karan Johar’s 2012 retelling of Agneepath that best exemplified this trend. The new script cast Sanjay Dutt as Kancha, earlier played by a very suave Danny Denzongpa, and introduced the character of Rauf Lala, played by Rishi Kapoor. Although Dutt had earlier portrayed thugs and corrupt policemen in films such as Thanedaar (1990), Khalnayak (1993), and Eklavya (2007), these were characters with redeeming, even likeable, qualities. Kancha was the embodiment of evil. He, quite literally, towered over Hrithik Roshan’s Vijay Dinanath Chauhan in every way, almost reducing him to utter helplessness. If Vijay finally managed to overpower Kancha, it was simply because the script said so. The other big surprise that Agneepath held was Rishi Kapoor, who had played the loveable, good-natured lover, husband and father so far. But now, his kohl-lined eyes shone with a menace never seen before.

It is as if established heroes and actors with chocolate boy images decided they had nothing to lose. And, of course, because being bad is fun. Villains have existed for the sole purpose of letting the hero be a hero. For what good is a hero, if the villain does not provide him with the opportunity to display his heroism? And although the villains of Hindi cinema have rarely got their due—Pran, however, is believed to have been paid more than Amitabh Bachchan for a period of time—they have been the ones who have made movie-watching fun and entertaining. They are the ones who brought in the glamour, the high-octane action and the final catharsis.

For, if Gabbar had never existed, Thakur would probably be leading an uneventful and sedate retired life in Ramgarh, twiddling his thumbs.

Danny Denzongpa (right) plays Kancha Cheena in Agneepath

Danny Denzongpa (right) plays Kancha Cheena in Agneepath

(Clockwise from top left) Ajit (left) plays gang leader Teja in Zanjeer Amrish Puri (left)as Mogambo in Mr India Kulbhushan Kharbanda (left) as Shakaal, the sadist crime lord, in Shaan

(Clockwise from top left) Ajit (left) plays gang leader Teja in Zanjeer Amrish Puri (left)as Mogambo in Mr India Kulbhushan Kharbanda (left) as Shakaal, the sadist crime lord, in Shaan (Clockwise from left) Karan Johar"s 2012 Agneepath saw Rishi Kapoor and Sanjay Dutt don menacing new avatars Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Gangs of Wasseypur II

(Clockwise from left) Karan Johar"s 2012 Agneepath saw Rishi Kapoor and Sanjay Dutt don menacing new avatars Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Gangs of Wasseypur II