Job creation: It's a full-time job

As India aims for higher growth, it not only needs a massive spurt in job creation but also more meaningful employment

The services sector contributes more to GDP and requires a labour force with high skills

The services sector contributes more to GDP and requires a labour force with high skills

Image: Umesh Goswami/ The India Today Group/ Getty Images

In a country where an estimated 1.2 crore to 1.6 crore people come into the workforce each year, jobs, or the lack of them, remain a cause for concern. With the 2019 general elections barely a year away, the discussion over how to revive a slackening pace of growth (6.6 percent in FY18 compared to 7.1 percent in FY17) is starting to get louder. India has a long way to go to touch the 9 percent growth that we saw a decade ago. However, even as the country aims for that, the need of the hour is to provide adequate employment to its growing labour force.

The data conundrum

According to a report titled ‘Jobless Growth?’ released last month, the World Bank said that even to keep employment rates constant, India needs to create 8 million jobs per year. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had, during an election campaign speech in November 2013, promised to create one crore new jobs each year if voted to power. Experts say it is difficult to assess how many jobs have actually been created, considering there is no updated and comparable data from a singular agency.

The Labour Bureau’s annual household employment survey of those working in the organised and unorganised sectors of the economy showed a decline in total employment in India from 48.04 crore in 2013-14 to 46.76 crore in 2015-16.

This survey has now been replaced by the Labour Bureau’s quarterly employment studies. However, these take into consideration only eight sectors: Manufacturing, construction, health, trade, transport, education, IT/BPO and accommodation/restaurants. This data reveals a rise of 1.22 lakh jobs during the period between October 2016 and January 2017 and 2.31 lakh jobs in total (in the nine months beyond April 2016), to help create a total employment of 207.53 lakh over the period, official data shows.

These figures—not yet verified—are based on responses from establishments which employ 10 or more workers, resulting in data collected from 10,600 units across India.

Another all-India study, from the National Sample Survey Office, under the ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, released in March 2018 reveals that the total number of workers across India in unorganised manufacturing firms (excluding construction), rose to 3.6 crore in 2015-16, from 3.48 crore in 2010-11.

Meanwhile, in January, the prime minister quoted from a payroll study that showed that 70 lakh new EPFO (employment provident fund) accounts had been opened in FY18. However, the study, prepared by IIM-Bengaluru professor Pulak Ghosh and State Bank of India’s group chief advisor Soumya Ghosh, has come under criticism from experts for various factors: That the creation of new EPF members does not necessarily indicate new jobs the data does not record how many informal jobs have turned into formal jobs it also does not account for job losses in FY17 and FY18 due to the impact of demonetisation and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

New jobs, particularly in rural India, were created under MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act). According to the MGNREGA website, the government provided employment across India to 3.94 crore households out of the 4.58 crore households that demanded employment, from 2014-15 to May 2018. However, only 17.4 lakh households availed of 100 days of employment, according to the website.

Low investment woes

All the statistics mentioned above, though subsets of a larger picture, show that jobs are being created, but not at the pace at which India needs them.

“We are growing at a rapid pace of 6-7 percent each year. However, jobs are not growing [that fast]. So, it is fair to say that we are seeing jobless growth,” says Mahesh Vyas, managing director and CEO of the privately owned Centre for Monitoring Industrial Economy (CMIE).

The main factor for the low rate of job creation is low investments, according to data from CMIE. The investment rate has fallen to 28.5 percent in 2017-18 from 34.3 percent in 2011-12. According to CMIE’s CapEx database, the value of new investment proposals has fallen steeply to ₹7 trillion in 2017-18 from ₹25 trillion in 2010-11.

Companies in the private sector have been plagued by high debt and bad loans, while banks with weak balance sheets have been unable to lend more for projects. Weak export demand has also hurt investment opportunities and local job creation. “Infrastructure projects and credit lending bottlenecks, existing inflexible labour regulations, skill deficit and even skill mismatches have led to the jobs problem,” says Radhicka Kapoor, a research fellow at economic policy think tank Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER).

From 2005 to 2010, when India’s economy grew by nearly 9 percent in four out of six years, the economy underwent a structural transformation by rapidly advancing from an agriculture-led one to a services-led one, whereas industrial development slowed down. Since then, the services sector has been providing more jobs than the labour-intensive manufacturing one which indicates that India has been unable to create voluminous jobs that lead to higher growth.

Today, the services sector is the largest contributor to the GDP at 54 percent followed by manufacturing (29 percent) and agriculture (17 percent), according to World Bank data. But the services sector requires a labour force with high skills, which has led to a skills mismatch. “More than 50 percent of India’s population, in fact, is illiterate or has studied till the primary level only,” Ritika Mankar Mukherjee and Aditi Singh said in an Ambit Capital report, on the jobs problem.

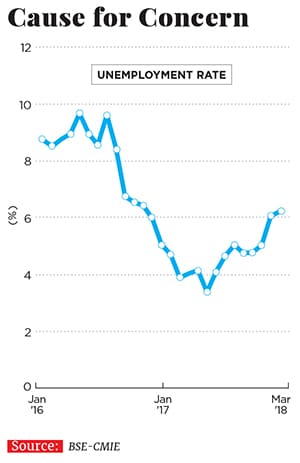

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate continues to rise. According to the Labour Bureau’s 2015-16 Employment Unemployment Survey data, the unemployment rate in India was estimated at 5 percent at the time. This is the percentage of people who were available for work, but could not find work.

Data from the BSE-CMIE collaborative venture places India’s unemployment rate at a much higher 6.23 percent for March 2018. In terms of number of unemployed, the International Labour Organization forecasts the unemployed in India to be at 1.86 crore in 2018 and 1.89 crore in 2019.

Automation and changing business models have also led to a slowdown in hiring. At three of India’s top IT firms—TCS, Wipro and Infosys—over 30,000 jobs were lost between 2015 and 2017, according to media reports.

Generating jobs

“There is no bigger challenge than to create jobs,” says ICRIER’s Kapoor, adding that the challenge is not just in creating jobs but also creating productive jobs.

A McKinsey June 2017 report indicates that gainful employment does not mean only quantity and simply creation of jobs, but also the creation of more fulfilling and better-paying jobs that are more productive. It means an enhancement in work “quality” (such as safety, cleanliness, flexibility, income security, skills and intellectual stimulation). The World Bank, too, in its draft World Development Report 2019, stressed on the need for creating more formal jobs if India is to join the ranks of the global middle class by 2047.

Considering most of India’s workforce has traditionally been in the informal, unorganised market, where the jobs are contractual and often without security or benefits, India will have to continue to strive to shift towards higher productivity jobs instead of low-skilled ones, analysts say. In India, the high-skilled and higher productivity jobs relate to IT, technology, automation, aircraft and railway maintenance, social media and cyber security.

Opinion is divided on how much India should depend on manufacturing to drive job creation. While Kapoor believes the manufacturing sector will need to drive future job volumes, HDFC Bank’s chief economist Abheek Barua warns India “not to do a China”, which had decades ago used large-scale manufacturing as a large employment generator. “Job creation will have to be more broad-based, beyond just brick and mortar. The use of large-scale manufacturing to create jobs had a place in a certain period in history, but not anymore,” he says.

The employment elasticity—which indicates the extent to which employment can increase due to an increase in GDP—for services and certain service sector categories like ‘other services’ (which include occupations such as coaching, recreational and sports activities, hair dressing, tailoring, ayurveda and wellness centres and salons) is higher than that for the manufacturing sector, Barua says in a March 2018 report. For every 10 percent increase in output produced, the manufacturing sector employment grows by 3.3 percent, mining by 3.4 percent, utilities by 11 percent, construction by 10 percent, services by around 4.4 percent and other services by around 4.7 percent.

In the coming years, as India continues to push towards higher growth, it is the services sector that is most likely to provide the impetus and also see more jobs. Other sectors such as startups, ecommerce firms and services, too, have the potential to create gainful and reasonably paying jobs, he adds.

The digital ecosystem, including startups—but for a short phase post-demonetisation, when capital became scarce—has, and will remain, a key driver for jobs. These jobs will be created in ecommerce firms, logistics and IT-enabled services. A McKinsey June 2017 report indicated that Ola and Uber combined provided up to one million jobs in 2017, compared to 0.3 million in 2015. Data from Nasscom shows that from 2014 to 2017, the IT and business process outsourcing sectors created between 550,000 and 600,000 incremental direct jobs.

Textiles, apparel, gems and jewellery, food processing and automobiles, too, will continue to be looked at to provide jobs, say analysts.

Meanwhile, the government needs to provide more incentives to the private sector, including specific segments that have higher sensitivity to growth such as infrastructure and construction. Until investments and incentives for the private sector fully kick-start, the government will have no choice but to keep its foot on the accelerator. India’s positive demographics (65 percent of the population is under the age of 35) need to be tapped into. Any sluggishness or delay could well result in the country’s demographic advantage turning into a demographic demon.

First Published: May 11, 2018, 18:32

Subscribe Now