In the post Covid-19 era, an opportunity to build back better

To combat the economic and social turmoil caused by Covid-19, a sustainability-led approach is vital to create resilient societies for the future

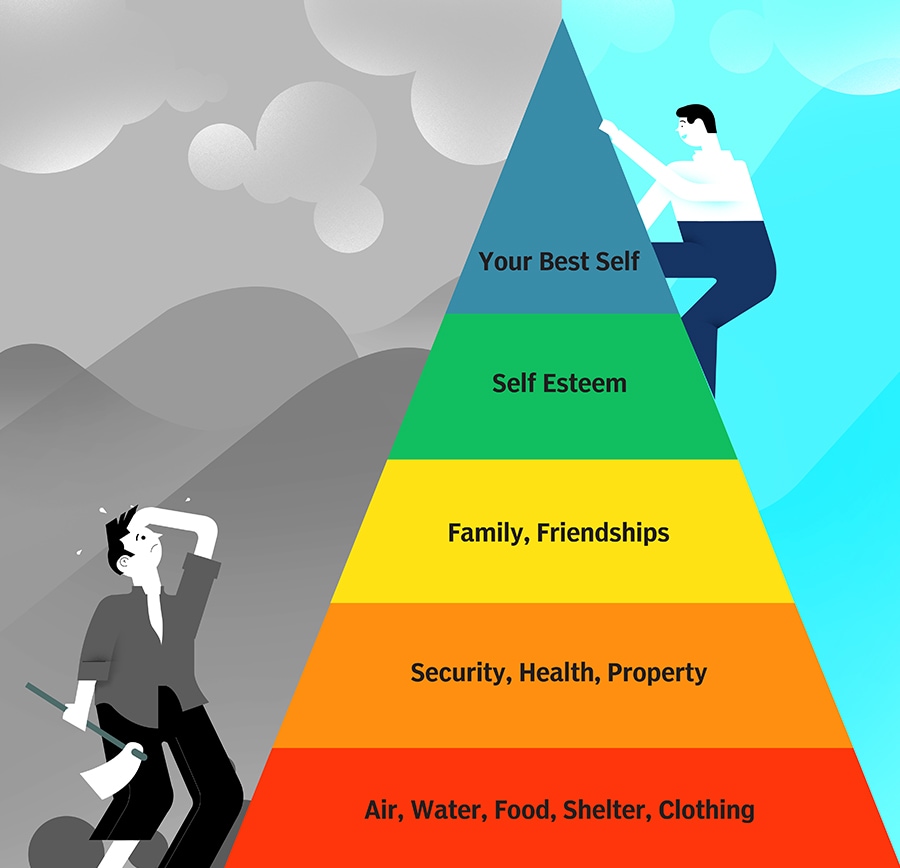

The world today is not equal. The United Nations" 2030 Sustainability Development Goals envision a sustainable and equitable world, where everyone has access to basic needs, healthcare, education, and more, and the opportunity to reach their fullest potential. Illustration by: Sameer Pawar

The world today is not equal. The United Nations" 2030 Sustainability Development Goals envision a sustainable and equitable world, where everyone has access to basic needs, healthcare, education, and more, and the opportunity to reach their fullest potential. Illustration by: Sameer Pawar

We have been here before. The Spanish Flu, Black Death, two World Wars. And we have bounced back. Whether it was 9/11, or 26/11 closer to home, human resilience has always found a way to live with new, albeit cautious, realities.

Here’s one of our current realities: Look out your window and bluer skies will look back at you the air is cleaner. A new study in Nature Climate Change journal has found that, compared to 2019, global carbon emissions fell 17 percent between this January and April due to the global lockdowns. It takes us closer to achieving Climate Action (SDG 13) and Life on Land (SDG 15), two of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which look to address by 2030 a set of global challenges that we face.

While the novel coronavirus has infected 55 lakh globally (over 1.5 lakh in India) and killed nearly 3.5 lakh, one of its unmissable, perhaps unintended too, gains has been the drop in pollution levels. India, too, witnessed its carbon emissions fall for the first time in four decades. But, as far as silver linings go, that’s about it.

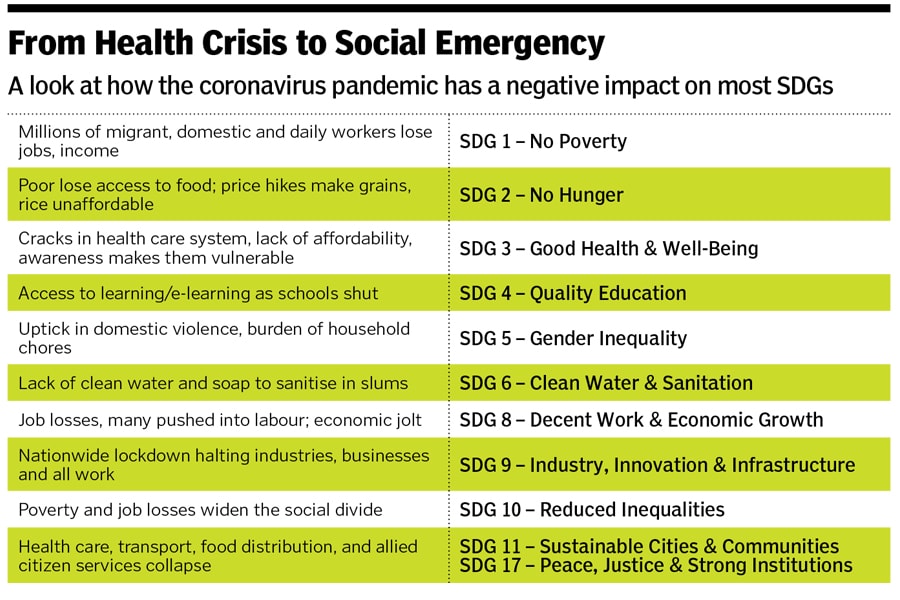

Beyond the obvious public health crisis, Covid-19 has laid bare a number of invisible fault lines that threaten our social fabric—the lack of health care, public and welfare distribution systems, or the vulnerability of the underprivileged (SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Those in vulnerable categories—like your domestic help—find themselves without basic necessities such as money (SDG 1: No Poverty), food (SDG 2: No Hunger), soap and clean water (SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitisation). The crisis has affected their children’s education (SDG 4: Quality Education), and their ability to keep a roof over their head (SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities).

As blue-collar staff are laid off by the thousands in the midst of widespread business shutdowns and as workers migrate back home, a health crisis has quickly turned into an economic and social meltdown. The absence of social safety nets has only exacerbated the crisis, setting us back on social development parameters that were around even before the SDGs were formed.

“This has been a stark reminder that people at the lower end of the economic pyramid suffer far more disproportionately,” says Satya Tripathi, assistant secretary general of the United Nations. A recent Oxfam report says half a billion people will fall back into poverty as a result of coronavirus-induced hardships.

Historically, countries have spent on public infrastructure to boost investments and create jobs to recover from economic dips. The world is about to spend $40-70 trillion on roads, bridges, ports, says Tripathi. “If sustainability is not a part of that plan today, you are looking at a bigger problem and accelerating the climate challenge. We need policy planners to look at the true cost of investments, of what we are willing to let go for it.”

The European Union, for example, is planning to weave climate action into its green economic stimulus for the private sector. It will also include biodiversity conservation in its recovery plan, noting that Covid-19 has shown how vulnerable its loss makes us. India, on the other hand, opened up coal mining to the private sector. “It’s an economic mistake,” says Pavan Sukhdev, founder-CEO, GIST Advisory, and goodwill ambassador to United Nations Environment Programme, when solar power is cheaper everywhere.

India has the world"s fifth-largest (9 percent) coal reserves (101.3 billion tonnes). Domestic production by private companies will help reduce imports—India was the world’s second-largest coal importer in 2018—and, in a way, transport and logistics emissions. A source close to the government adds that the Centre can’t just let the coal sector die—“it accounts for millions of jobs. Until 2050, coal is here to stay around the world.”

At the same time, renewable energy needs to be ramped up to reduce dependency on coal. As Rahul Munjal, chairman and managing director, Hero Future Energies, puts it, “Till the world comes up with solutions for climate engineering, we will have to ensure we replace as many gigawatts of fossil fuels with clean energy.”

Investor interest in renewable energy can be gauged from the oversubscription of the state-run NHPC’s recent auction of 2 GW of solar projects at tariffs lower than the 2019 average, and despite Covid-19 uncertainties, as reported by Bloomberg NEF. The government is also looking to display its eagerness to push for clean energy. “The Ministry of New & Renewable Energy is continuously auctioning renewable projects. Strong track record and policy clarity seem to have driven investors to take the risk. The government is advancing many tenders that were in the pipeline to signal that India is not stopping [on renewables],” the source adds.

Apart from the pandemic, eastern India has been ravaged by cyclone Amphan, while the north is experiencing a heatwave and the west is swarming with locusts. At a time like this, returning to business as usual without building better businesses will reinforce the status quo, says Sukhdev. “It’s a free lunch for the companies to create private profits at the cost of public losses. That’s exactly what happened in 2008 [financial crisis]. And that’s exactly what has happened today.”

If social cost and climate change fail to drive home the urgency, consider this: Frequent zoonotic diseases, where the pathogen jumps from animals to humans, in the last 20 years—Sars, Ebola, Zika, Mers, swine flu, and now Covid-19—are a direct result of our actions, including removing the forest frontier between animals and humans. We are reaping the horrific results, says Tripathi, also the head of UNEP"s New York office. Sukhdev dubs this a wake-up call.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) recently noted that frequent epidemics are coinciding with globalisation, urbanisation and climate change: “…as coronavirus spreads, so does the sobering reality that epidemics will become more common with our increasingly connected age.”

Which means, you cannot repeat the same economic and business models that brought us here and expect a different result, Sukhdev warns. This may be the perfect time to reset and create an equitable and sustainable world that is resilient enough to face such challenges in future.

The economic fallout of Covid-19 is debilitating. The International Monetary Fund’s Chief Economist, Gita Gopinath, estimated a global GDP loss of $9 trillion—the worst since the Great Depression [of the 1930s], she said in a blog, and far worse than the global financial crisis [of 2008]. Everyone is looking for a definitive blueprint to recover from the economic toll. Meanwhile, a ready reckoner has been out there since 2015: The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Sustainable Development Goals agenda with 17 goals and 169 targets that can usher in economic growth and equity by 2030.

However, it stands to be shelved as the government and corporations try to find a way back to black with limited resources. “We have serious doubts about the availability of resources to do the right thing and achieve SDGs. And climate change is 100,000 times bigger,” says Tripathi. In 2019, India ranked 115 out of 163 SDG members, lagging behind on most goals except climate action and poverty. The pandemic is expected to set the country back even further.

But that doesn’t need to be the case. Weaving the principles of SDGs into our Covid-19 recovery plans could help both—the economy and the planet.

Sukhdev wants to tell everyone who will listen: Sustainability and economic performance together is possible. “A lot of precious tax dollars [stimulus] are going to be recycled and wasted into the economy as people don’t understand the importance of investing in the new economic model that has more resilience and less likelihood to fail in the way we are seeing currently.”

Munjal adds, “The question is not how companies will profit from going green, it is about how the companies will connect with their end consumers at a deeper level by doing the right thing.”

In January, Sukhdev won the Tyler Prize for Environment Achievement, often called the Nobel Prize for environment. In 2009, he led the UNEP’s Green Economy Initiative that became a 600-page study in 2011. It hypothesised that if governments around the world dedicate one-tenth of total annual investment into greening the economy instead of fossil fuel discovery or mining, the results would be incremental: GDP per capita would grow by 2.5 percent in five years, forest cover by 8 percent and water demand will fall by 21 percent. On a 50-year horizon, GDP per capita will improve to 14 percent. “This massive impact doesn’t decrease investments, it doesn’t mean more taxes. It’s just a change in direction,” Sukhdev says.

As Covid-19 triggers reverse migration to villages, that’s where jobs have to be created in the days to come. “The stimulus that comes for the economy has to be at the village economy level. India needs to stop copying China [to become an export-led economy], it’s a wasted philosophy and we will only destroy good capital and ruin the economy,” he adds.

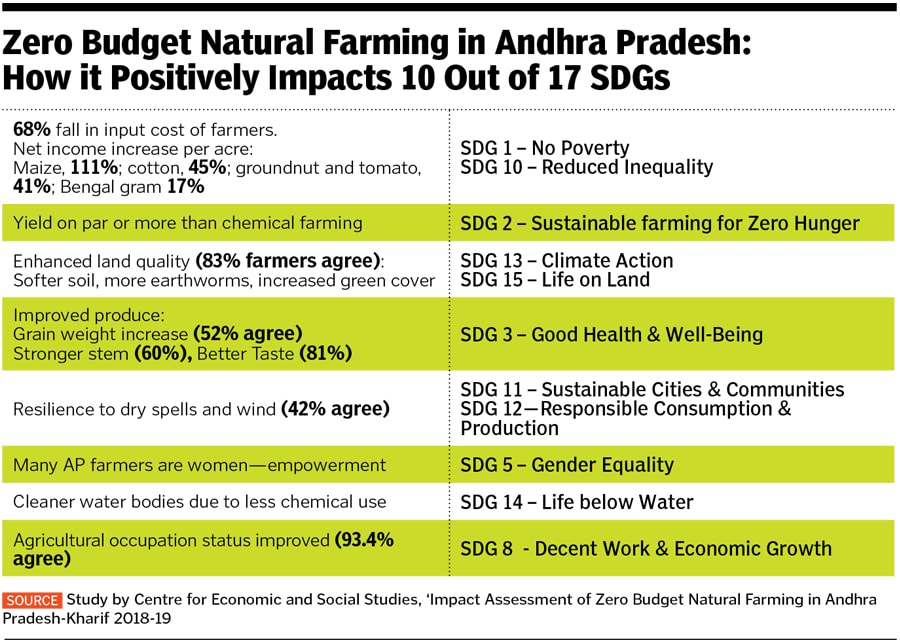

According to the 2015-16 agriculture census, there are 14.5 crore farmer families in India for them, natural farming can create millions of jobs and better incomes. For instance, by September 2018, 3.54 lakh farmers in more than 1,000 villages in Andhra Pradesh adopted zero budget natural farming as an alternative to fertiliser-based farming. A recent study showed the practice benefited 10 out of the 17 SDGs (see table). The most significant impact has been a better yield and income. By 2024, Andhra Pradesh wants its 6 million farmers to adopt the project and, by 2026, cover 8 million hectares of cultivable land.

The impact of a business on society is not only financial. Sukhdev has been an advocate of measuring corporate performance by evaluating human capital (knowledge, skills, jobs), natural capital (natural resources, environment and climate), social capital (inequality) and financial capital. “It should not be an option to have a social and natural cost and not declare them.” GIST Advisory plans to launch its impact measurement platform, which includes all these parameters, on World Environment Day on June 5.

Governments, however, will have to lead the way. “It’s time to cut income tax and increase taxes on mining. Procurement of sustainable buildings, vehicles, energy, will also steer the private sector to the new economy,” he says. Niti Aayog, the Centre’s policy think tank, however, declined to comment on India’s commitment to SDGs as “decisions were yet to be made”.

Sustainability is good business, UN’s Tripathi says. Take the example of Ambuja Cement, which despite being a water-intensive business, has been water positive for six or seven years, giving back more than it consumes in the areas where its plants operate. Ambuja Cement says it counts on the support of local villages for its operations, lowering the risks of unrest from local communities. During the Covid-19 pandemic, it reached out to provide health kits (2 lakh masks), spread awareness and food security (ration kits for 60,000 families), touching 6 lakh people living near their plants.

It also adopts the triple bottom line accounting model (people, planet and profit) to evaluate its financial, environmental and social health, similar to Sukhdev’s four-dimensional approach. “Every year, we assess our negative and positive social and environmental value, along with financial performance to understand how they impact the company’s future,” says Neeraj Akhoury, MD and CEO, Ambuja Cement.

The goal is to become the most competitive and sustainable company, and yet go beyond mere profits. “It helps us make strategic decisions and identify a portfolio of cost-effective projects. We are able to increase our earnings by keeping costs down,” Akhoury said. As Ambuja Cement reopens operations in a phased manner, he says the company will live up to its social responsibility even as it ensures business continuity.

Anantshree Chaturvedi, vice chairman and CEO of FlexFilms, which believes future-proofing any commercial business now needs to be centred around sustainable products and being carbon neutral, says, “We have chosen to make the tough decision and walk away from clients when we saw their sustainable goals were just promises to boost their stocks. The need of the hour is for corporates globally to understand that unless we start focusing on the environment and SDGs, we may not have enough people left to make profits out of.”

Consider that since Covid-19, ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance)-linked indices (S&P 500 ESG Index, the MSCI Emerging Markets ESG Leaders Index and MSCI AC Asia ESG Leaders Index) have outperformed parent indices on a total return basis, with top-scoring ESG firms presumed to be better equipped to deal with unexpected risks like this pandemic, wrote Calvin Quek, senior environmental specialist, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in an article recently. UN’s Tripathi says sustainability is not something the good guys do. You have to do it if you want to remain in business.

As the world wakes up to new realities, a unified call for action from people around the world will also force companies towards sustainability. “Profits are not bad,” Sukhdev signs off, “but if you do it at the expense of public losses, don’t expect to have a healthy economy or people.”

First Published: Jun 05, 2020, 16:37

Subscribe Now