“Why do I need to wear these to go see a recycling plant?" I asked.

“There will be plastic all around, so you never know what could hit you, literally," she replied.

She was right. The complexity of what goes on inside a recycling unit is unimaginable: From tonnes of waste being fed into gigantic cleaning machines, colourful clean plastic shreds looking like confetti being poured out, and finally those granules being put through intensive testing.

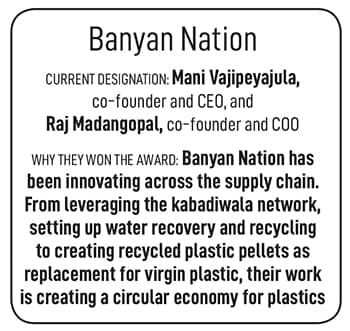

Their work is crucial to the ecosystem as of the 3.4 million tonne waste that India generates, only 30 percent is recycled—the rest finds its way to landfills, says Marico Innovation Foundation’s (MIF) ‘Innovations in Plastics: The Potential and Possibilities’ report.

Consumption of plastics, on the other hand, was at 19.8 million tonne in 2019-20 and growing at 9.7 percent. Clearly, plastics are irreplaceable.

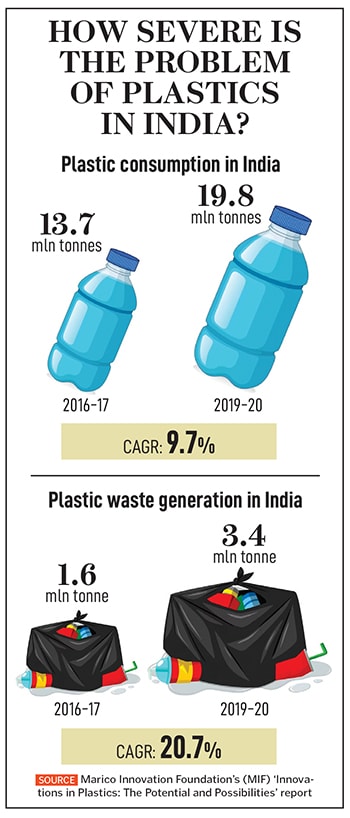

“Plastics is one of the most versatile innovations of our times, and it is its single-use nature that has made it an ecological and environmental poison," says Madangopal, co-founder and COO. Banyan Nation’s goal is to reduce the amount of virgin polymer being produced, and instead use recycled plastic, thus making it easier to manage. Madangopal adds, “The more virgin polymer you produce, the more trash you are creating."

![]() Banyan Nation collects more than 1,000 tonne of plastic waste per month, and converts them into granules that are reusable, thereby creating a circular economy.

Banyan Nation collects more than 1,000 tonne of plastic waste per month, and converts them into granules that are reusable, thereby creating a circular economy.

How do they do this? Vajipeyajula explains: “Through our digitised and traceable informal supply chain—the kabadiwalas’ network—we collect discarded High Density Poly Ethylene (HDPE) and Polypropylene (PP) plastics, such as detergent bottles or toilet cleaners. Once collected, the recycling process begins: First the cleaning technology removes all contaminants, labels, adhesives, inks, dirt etc. After an intensive process, they are converted to granules, comparable to virgin HDPE plastics in quality and performance." Once sold to large FMCG players such as Hindustan Unilever or lubricant companies, these granules are used to make plastic containers all over again, thus closing the loop.

Around 2011-12, when the duo was planning to work in the field of waste management, they realised that PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottle recycling in India is fairly common. “The issue," adds Vajipeyajula, “is with HDPE and PP, which are far more versatile resins when compared to PET. PET water bottles are clean and transparent. They are mainly used for water and soda bottle applications and have an easily removable label. Whereas the HDPE/PP bottles such as lotion or shampoo bottles have labels, colours, inks, prints and remnant products. This makes working with HDPE/PP more complicated." In order to remove these entirely, they developed a washing technology in-house. If these aren’t eliminated properly, the recycled plastics will have impurities, eventually being converted to low-value products such as benches, tables, buckets, etc.

Sumaira Abdulali, the convenor of NGO Awaaz Foundation, explains the issue with HDPE and PP plastics: “Though both of these are easily recyclable, in India because of problems in the collection systems and due to the contamination of the plastics collected, PP is more commonly recycled while HDPE recycling systems lag. It is important to note and streamline these lacunae in our systems."

Early Days

Vajipeyajula had worked at Qualcomm in Silicon Valley and then went to business school for two years, which is when he spent a lot of time at recycling facilities in New York. He met Madangopal, when they were studying at the University of Delaware. Till 2013, he was working at a tech company in Seattle, after which both of them decided to move back to India to work in the space of plastics and waste management.

![]() The duo had no clear business model back then. Vajipeyajula recalls his early pitches to investors, “Raj and I were well trained in solving complex engineering problems and we wanted to apply our skills to tackle the problem of plastics pollution in India." Investors thought both were crazy.

The duo had no clear business model back then. Vajipeyajula recalls his early pitches to investors, “Raj and I were well trained in solving complex engineering problems and we wanted to apply our skills to tackle the problem of plastics pollution in India." Investors thought both were crazy.

In 2014, there was no data available on the amount of waste being generated. “We developed this data intelligence platform to map out informal sector kabadiwalas and recyclers in the supply chain," says Madangopal. Initially, they had five to six people on bikes to collect this information in Hyderabad—the data included geo-spatial coordinates, phone numbers, pricing, volumes and other key information regarding the materials they were collecting. Using this, they built a small-scale platform in a month’s time.

“We have close to 40 people across five states, still collecting data from informal recyclers and we now work with most of them," he adds. Now they have a dataset of 10,000 kabadiwalas and aggregators across 20 states.

“The recycling industry in India is not an organised activity and this lack of systems presents several problems in collection, transport, quality control etc," adds Abdulali. The founders’ idea was to address this by leveraging the informal recyclers’ network, and build a solution empowering them, instead of plugging in an already existing Western technology in India. After training all these recyclers, Banyan Nation works closely with them, buying segregated plastics waste from them.

Between 2014 and 2019, the duo spent time researching and searching for a scalable model. “Finally," adds Vajipeyajula, “in 2019, we found our customer, our product, we knew our supply chain and we knew our stakeholders. It was the culmination of all our work in those five years. We never wanted to build just a technology and push it into the market. We wanted to solve the problems across the value chain." And once they had this in place, it was about getting brands on board.

After the waste comes to the Pashamylaram unit in Telangana, the plastics undergo ‘washing’. However, this process is extremely water-intensive.

“We have invested in a state-of-the-art, water recovery, recycling and management system, that ensures that we not only use the best quality water, but also that we recover close to 100 percent of the water that we are consuming… hence minimising the depletion of ground water on a day-to-day basis," explains Madangopal.

Eventually, the recycled plastic granules that are sold to MNCs are that of almost virgin quality. He says, “So far, brands had only worked with virgin polymers and their manufacturing units were designed accordingly. We had to collaborate with them on incorporating recycled plastic granules." In 2018, they signed their first major contract with Hindustan Unilever, and have continued working with them since.

Scaling-up Challenges

Across the country, there are more than 3,100 landfills, of which most have surpassed their waste capacity years ago. These sites are two to three decades old and currently receive about 2,000 (Bhalswa, Delhi) to 9,000 (Deonar, Mumbai) metric tonne of solid waste daily. Clearly, waste management is more of a real estate problem now.

![]() The larger issue, though, points out Madangopal, “is not that of creating the right technology, but instead a mindset problem of stakeholders across the board—from the masses, to the government and corporates—that recycled plastics are somehow inferior to virgin plastics and they have to be cheaper as well".

The larger issue, though, points out Madangopal, “is not that of creating the right technology, but instead a mindset problem of stakeholders across the board—from the masses, to the government and corporates—that recycled plastics are somehow inferior to virgin plastics and they have to be cheaper as well".

And it continues even now as Banyan Nation’s entire supply chain is fully operational. “Most brands compare the cost of recycled plastic to the cost of virgin plastic. But that is an unfair comparison to make. In contrast to virgin plastics, recycled plastics have a lot more operational overheads such as collection, segregation, washing and cleaning. At the end of the day, it is the cost of cleaning up the planet vs the cost of trashing it," adds Vajipeyajula.With their existing clients, the company has produced over 0.5 billion FMCG containers from recycled plastic in the past year. Their gross income for FY22 was ₹25.7 crore as compared to ₹12.6 crore for FY21, as per financial data provided by business information and analytics platform Tofler.

Banyan Nation has also won a number of national and international awards, including the World Economic Forum Global Technology Pioneers (2021), Circulars Award at the World Economic Forum (2018), Intel-DST Award Innovations for Digital India (2017) and many more.

“The company has a strong business case for a circular-economy approach that encourages manufacturers to consider the implications of recyclability and resource conservation. Banyan Nation’s goal—which is aggressive but achievable—is to help transform the way India consumes, recovers, recycles, and views plastics as a resource," according to a spokesperson at KKR India, who gave a grant of an undisclosed amount to Banyan Nation in 2016. So far, the company has raised a total of $14.3 million in funding, according to Crunchbase.

Expanding Further

Banyan Nation’s capacity stands at 1,000 tonne per month. In the next three years, they are hoping to expand this to 50,000 tonne per annum, across a diverse range of markets. So far, they have worked mostly in South India, but hope to expand their footprint pan-India. They are also shipping to the Middle East, Europe and Southeast Asia. On the innovation front, they are introducing a ‘Refresher’ machine, which will produce odour-free recycled plastic pellets. “Deodorization will be the last stage in the process and it gets rid of dozens of contaminants and odors," explains Vajipeyajula.

Banyan Nation caters to eight to 10 clients, mostly in the FMCG and lubricant sector, such as Hindustan Unilever, HPCL and Reckitt. However, they hope to move into food-contact containers, such as juice bottles or milk bottles. But, to produce recycled plastic that’s certified to have food contact, Vajipeyajula explains, “The input feedstock—the waste plastic that is added—has to be highly curated. You cannot add waste lubricant or toilet cleaning bottles to form granules that can be used to make cooking oil cans."

The additional refresher technology allows them to move into this segment, and the US FDA has already issued a letter of no-objection for this technology to be used in food contact applications. “However," he adds, “We are awaiting the FSSAI’s go-ahead before we start manufacturing pellets for this segment."

With problem-solving at the core of what they do, these Climate Warriors hope to continue making a significant contribution to the plastics problem in India.

Banyan Nation collects more than 1,000 tonne of plastic waste per month, and converts them into granules that are reusable, thereby creating a circular economy.

Banyan Nation collects more than 1,000 tonne of plastic waste per month, and converts them into granules that are reusable, thereby creating a circular economy. The duo had no clear business model back then. Vajipeyajula recalls his early pitches to investors, “Raj and I were well trained in solving complex engineering problems and we wanted to apply our skills to tackle the problem of plastics pollution in India." Investors thought both were crazy.

The duo had no clear business model back then. Vajipeyajula recalls his early pitches to investors, “Raj and I were well trained in solving complex engineering problems and we wanted to apply our skills to tackle the problem of plastics pollution in India." Investors thought both were crazy. The larger issue, though, points out Madangopal, “is not that of creating the right technology, but instead a mindset problem of stakeholders across the board—from the masses, to the government and corporates—that recycled plastics are somehow inferior to virgin plastics and they have to be cheaper as well".

The larger issue, though, points out Madangopal, “is not that of creating the right technology, but instead a mindset problem of stakeholders across the board—from the masses, to the government and corporates—that recycled plastics are somehow inferior to virgin plastics and they have to be cheaper as well".