Despite what seemed like an impossible task, in just a few months the team put together a demonstrator. In 2012, it unveiled the electric MObility (eMO) engineering study concept at the North American International Auto Show, where the Tesla Model S was also unveiled. “Over the last 10 years, we’ve taken the IP from there and used it on client vehicles," says Harris.

Cut to 2019. The Tata Technologies engineering team was entrusted with yet another Herculean task. Instead of building an electric vehicle (EV) from ground up—which would take about four years—Tata Motors decided to turn existing internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles into EVs. In theory, it was as simple as replacing the existing parts with those of an EV. In reality, things were a lot more complex. For instance, consider placing the 300 kg lithium-ion battery pack at the rear end of the car, while still maintaining its balance. This is only one of the many challenges, the team faced. Despite which, within a record time of 18 months, they managed to have Tigor’s EV version ready for production.

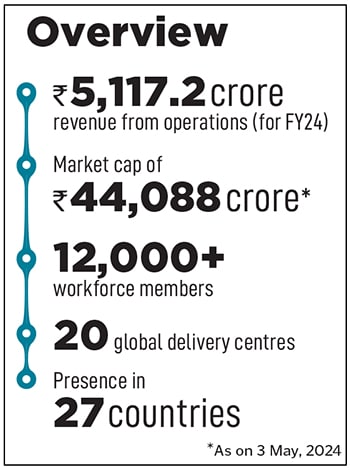

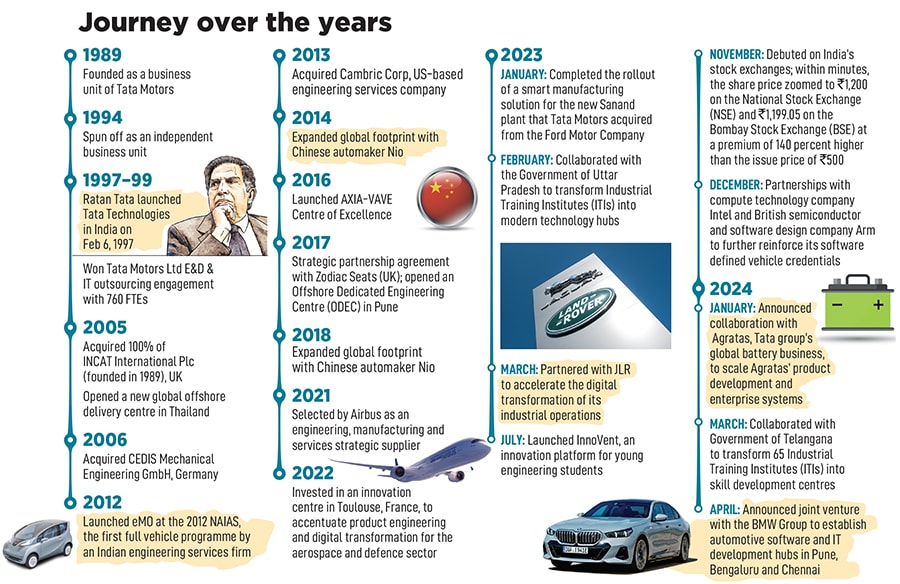

While the company traces its roots back to 1989, it was only on November 30, 2023 that the company got listed on Indian stock exchanges. The first public issue by a Tata company in almost two decades saw a blockbuster listing, with a premium of 140 percent to the issue price of ₹500. The company currently has customers including Honda, Ford, Airbus, VinFast and Jaguar Land Rover.

With a market capitalisation of ₹44,088 crore and immense potential in the EV market, there is no stopping the global ER&D giant.

The beginning

In 1989, the company was founded as the outsourced engineering and IT unit of Tata Motors. In 1994, the division was hived off as a subsidiary and named Core Software Systems. It continued to serve Tata Motors’ needs almost exclusively. In 2001, the company was renamed Tata Technologies. Around the same time, Ratan Tata, the then chairman of Tata Sons, approached Harris, the then CEO of UK-based INCAT International, with the idea to acquire INCAT. After visiting India, Harris recalls, “I was taken by the whole Tata story, its value system and the commitment to nation building in India." Finally, in 2005 the company acquired 100 percent of INCAT.

This was a major turning point, since INCAT was bigger and brought in marquee customers, critical capabilities, and a presence in major manufacturing hubs worldwide. On the other hand, Tata Technologies brought in scale, cost competitiveness, and access to high calibre Indian engineering talent. “It represented a rare instance of a truly synergistic deal," Harris tells Forbes India during an interaction at the company’s Hinjewadi campus in Pune. In 2014, Harris took over as CEO of Tata Technologies.

![]()

Focus on auto

In 2008, Tata Motors acquired the Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) businesses from Ford Motor Company for $2.3 billion. This was only a few years after Tata Technologies acquired INCAT. “We were positioned to support the delivery of their [Jaguar Land Rover] product plan, which gave us the opportunity to demonstrate our capabilities at scale. The Discovery Sport was the first full vehicle that we took responsibility for," says Harris.

For two decades, Tata Technologies has been a partner for JLR, deeply involved in engineering and digital services. “Our collaboration spans numerous key domains, such as our ongoing model-year vehicle programmes and the pioneering factory monitoring solution implemented across JLR plants," says Barbara Bergmeier, executive director, Industrial Operations, JLR. “Recently, we’ve embarked on a transformative ERP solution for our industrial operations, a testament to our profound trust in Tata Technologies. Their role is crucial as we transition to offering all our nameplates in electric by 2030, supported by an annual investment of 3 billion pounds in our product portfolio."

![]() Tata Motors has been the company’s oldest and key client. “We rely on Tata Technologies for their vast and extensive global expertise, and support on various aspects of engineering, which makes them an integral part of our business growth journey," says Anand Kulkarni, chief products officer, head of HV programs and customer service, Tata Passenger Electric Mobility. “As partners, we leverage their technical expertise when it comes to engineering in the mobility domain. Their dependable support is crucial to our business, enabling us to innovate and refine our mobility solutions to meet the fast evolving market demands."

Tata Motors has been the company’s oldest and key client. “We rely on Tata Technologies for their vast and extensive global expertise, and support on various aspects of engineering, which makes them an integral part of our business growth journey," says Anand Kulkarni, chief products officer, head of HV programs and customer service, Tata Passenger Electric Mobility. “As partners, we leverage their technical expertise when it comes to engineering in the mobility domain. Their dependable support is crucial to our business, enabling us to innovate and refine our mobility solutions to meet the fast evolving market demands."

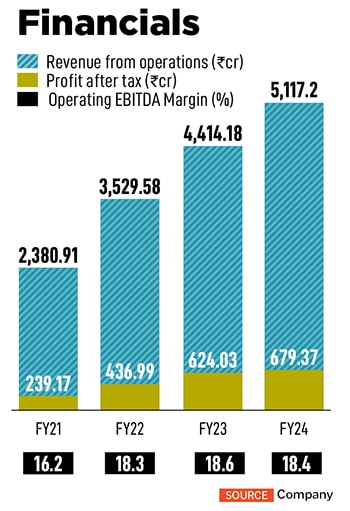

Apart from JLR and Tata Motors, the company has been working with auto companies like China-based Nio, Vietnam-based VinFast, Sweden-based Volvo Cars, Amsterdam-based Stellantis and others in the United States such as Tesla and Rivian. In FY24, the company clocked in a turnover of ₹5,117.2 crore, of which the automotive sector accounts for 87 percent of revenue, and this is expected to continue growing.

Recently, the BMW Group and Tata Technologies signed an agreement to form a joint venture with the aim to establish automotive software and IT development hubs in Pune, Bengaluru and Chennai. This will deliver automotive software, including software-defined vehicle (SDV) solutions for BMW Group’s premium vehicles and digital transformation solutions for its business IT. “This collaboration will accelerate our progress in the field of SDV. In international comparison, India boasts a large number of talents with outstanding software skills, who can contribute to our software competence," says Christoph Grote, senior vice president of Software and E/E Architecture, BMW Group.

“There was this notion that they [Tata Technologies] don’t do automotive software as much as mechanical design. But this deal will help them demonstrate the company’s evolving software ER&D capabilities," says Abhishek Kumar, equity research analyst, JM Financial.

Hedging their bets

While auto remains core to Tata Technologies, it has also been serving clients across verticals like aerospace and industrial heavy machinery. A large share of the latter business came with the acquisition of US-based engineering services company Cambric Holdings in 2013. This sector includes construction, farm, off-road specialty vehicles, and “the industry typically lags automotive by about five or six years," explains Harris. This means the company can use technology vectors similar to those in automotive, positioning them well as compared to competitors.

On the other hand, in 2021 Tata Technologies was empanelled with Airbus as a manufacturing, engineering and services strategic supplier. “This is a prestigious programme globally, we are one of 17 companies that are a part of it and have started to compete for the €2 billion annualised spend. We have built up a sizeable order book that we are now starting to discharge," says Harris.

![]() The company expects Airbus to be among its top five customers in the next three years and the sector’s revenue contribution to increase to 25 percent.

The company expects Airbus to be among its top five customers in the next three years and the sector’s revenue contribution to increase to 25 percent.

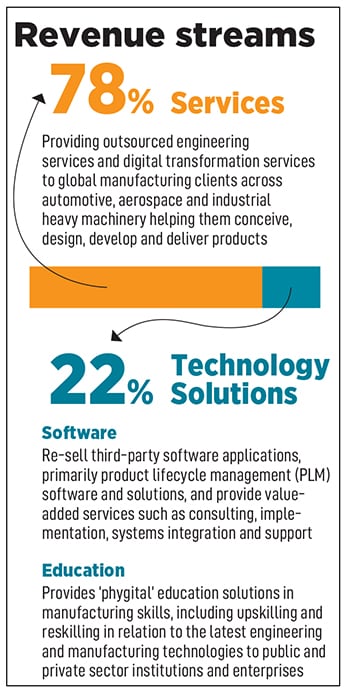

As of FY24, about 78 percent of its total revenue was from services and the rest from the technology services business (see box). “So what we do in tech solutions is not completely removed from what we do in services, our core offering. In fact, it adds to the value that we are delivering on the services side of the business," explains Savitha Balachandran, chief financial officer, Tata Technologies.

The company’s revenue has been growing since 2014. “We divested a lot of our software business, which was about $140 million. It was a relatively transactional business and didn’t attract a high degree of attached services. We sold that business in UK, France, Netherlands and Germany," explains Harris. “The services business was growing and we have been scaling since 2001. But growth rates appeared to be tapered since we were divesting."

Apart from revenue, operating EBITDA margins have grown too, from 16.2 percent in FY21 to 18.4 percent in FY24. “We increased offshoring to about 40 percent—earlier it used to be 30 percent—and in our industry that has the biggest impact. And some pyramid correction within our organisation structure… we used to have a hefty middle. We now have a campus recruitment programme," explains Balachandran.

Standing out

Tata Technologies finds itself among experienced peers, including the likes of KPIT, Tata Elxsi and L&T Technology Services. Harris says, “There’s intense demand. The industry is supply driven if you have the capabilities, the Intellectual Property [IP] you can move business." Increasingly, customers have been sourcing based on the confidence and trust they have in the capability. “This business is different from the IT services business. When you are being trusted with the next generation product, you’ve been entrusted with the family jewels of that manufacturing company, and that is more important than pricing and certainly cost arbitrage," he says.

Experts believe it is Tata Technologies’ experience within the EV space that will prove to be a massive differentiator henceforth. The demand for EVs is rising, and Tata Technologies is ready for it.

According to a report by International Energy Agency (IEA), electric car sales neared 14 million in 2023, 95 percent of which were in China, Europe and the US it was 3.5 million higher than in 2022, a 35 percent year-on-year increase. This is more than six times higher than in 2018. “With anchor clients like Tata Motors, who is the number one EV player in India, and JLR, which has committed a lot of capex towards electrification, it means they have a huge opportunity," adds Kumar.

“We feel that we offer something different to the sector, given the focus on complexity and turnkey product development," says Harris. Case in point—delivering two EVs for Vietnam’s VinFast in record time. “We were aware that VinFast had no real capability in terms of engineering a product, certainly not an EV. So, we had people in the styling studio, we did concept engineering, detail and mechanical engineering of the components, subsystems, testing the validation and confirming regulatory approval in different parts of the world. It was an end-to-end responsibility."

Synergies with Tata companies

Tata Technologies is one of the many companies that shares synergies with many Tata group companies, be it as customers, partners or sometimes even competitors. One of the closest competitors though is Tata Elxsi, which is exclusively focussed on software and electronics, whereas Tata Technologies looks at the entire value chain.

Kshitij Saraf, associate, equities, at Tusk Investments says, “The whole interplay among the Tata group companies is exceptional. If we look at the vehicle ecosystem, from designing and engineering to production and vehicle-to-vehicle communication—which we will see soon—is all taken care of by various companies within the group."

Outside of expanding within its existing verticals, earlier this year Agratas, Tata group’s global battery business, and Tata Technologies announced their collaboration to scale Agratas’ product development and enterprise systems, supporting the design, development and manufacturing of best-in-class battery solutions. This marked its entry into this growing industry. Tom Flack, CEO, Agratas, believes this partnership will help them in leveraging Tata Technologies’ expertise “in EV engineering, including competitive design, packaging and integration of battery packs that are critical for the performance of our customers’ products, from next generation EVs to energy-dense storage solutions."

“This is also backward integration for Tata Motors and JLR," adds Saraf. The collaboration with Agratas is one more example of how group companies are synergising and working together. “Our collaboration with Tata Technologies also maximises inter-group synergies and business excellence, showcasing the strategic benefits of being part of the Tata group," adds Flack.

Overcoming challenges

Until FY22, Tata Technologies’ top five clients included Tata Motors and JLR, both of which are part of the group. Analysts believe that reliance on group companies might prove to be high risk. Harris is aware, and says, “We are very conscious of this." In 2014, the earnings from JLR and Tata Motors —its anchor clients—contributed up to 75 percent of Tata Technologies’ revenue. By the end of the third quarter of FY23, Tata Technologies had limited its exposure to anchor customers—down to 39 percent from a peak of 69 percent in 2014-15. “We were very deliberate about focusing on taking the skills and value proposition that we incubated inside of the Tata group to the broader market," he says. Hence, in the last few years, the company is following an aggressive diversification strategy.

![]() As a services player, growth tends to be limited to 15-20 percent, says Saraf of Tusk Investments. “In order to see exponential growth, the company should continue looking at joint ventures outside the Tata group—as with BMW—where they co-invest with clients. I think that is going to be a big game changer."

As a services player, growth tends to be limited to 15-20 percent, says Saraf of Tusk Investments. “In order to see exponential growth, the company should continue looking at joint ventures outside the Tata group—as with BMW—where they co-invest with clients. I think that is going to be a big game changer."

While the company is extremely bullish on EVs, players in this segment globally are facing a lot of pressure. “In the near term, it might have some impact on demand, because companies might be looking to generally cut down or they are delaying the launch of models. But in the medium term, this kind of pressure will trigger offshoring, which will benefit all these offshore players," says Kumar.

Additionally, skill development is also a major challenge. There are 1.2 million engineers who graduate in India every year, but only 20 percent of them are industry ready. Tata Technologies is addressing this issue through its education proposition by working with state and private institutions to ensure engineers have the right skillsets. “The idea is how do you create a complete learning system, from course development to way of delivery that can help upgrade talent all the way from campus to corporate," says Balachandran. For those who graduated 20-30 years ago, they can upskill via the company’s e-learning platform myigetit.com. There are close to 50,000 engineers globally that subscribe to this platform.The next big thing

India is likely to contribute 22 percent to the global ER&D sourcing market by FY30. Software, automotive, and semiconductor sectors are expected to contribute over 60 percent of India’s share of ER&D sourcing by FY30, according to a report by Nasscom and BCG. The report reveals that India’s share in the global business ER&D sourcing is projected to increase from $44-45 billion in 2023 to $130-170 billion by FY30. Clearly, Harris has nothing to worry about. “There is more than enough opportunity among our current sectors to satisfy growth rates," he says.

But is there potential for expansion to newer sectors? Auto companies in China, for instance, are increasingly becoming vertically integrated, thus becoming very competitive in terms of price points. “This means companies are now looking for a full-stack proposition—from embedded electronics, mechanical solutions and more. I think that will push us into semiconductor and chip design areas," explains Harris. If they move into this area for auto, it might provide opportunities in the communications and other adjacent sectors as well.

Going forward, Harris suspects, “companies are going to focus on what they are great at… their core. And the rest, will be outsourced. This will present a bow wave of opportunity for engineering companies like ourselves, and that is adding confidence in the financial markets as well."

After the blockbuster IPO, people have been telling Harris: You’ve done the IPO, are you going to step down? “I just roll my eyes," he says with a laugh. “This time couldn’t be more exciting for Tata Technologies. So, I’m not going anywhere. We’ve got a lot of work to do."

![“We feel that we offer something different to the [ER&D] sector, given the focus on complexity and

turnkey product development.†Warren Harrism, CEO & Managing Director, Tata Technologies. Image: Mexy Xavier](https://images.forbesindia.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/media/images/2024/May/img_234397_warrenharris_bg.jpg?im=Resize,width=600,aspect=fit,type=normal)

Over the last 35 years, Tata Technologies has been pushing the boundaries and innovating fiercely. It has turned into a global engineering research and development (ER&D) powerhouse.

Over the last 35 years, Tata Technologies has been pushing the boundaries and innovating fiercely. It has turned into a global engineering research and development (ER&D) powerhouse.

Tata Motors has been the company’s oldest and key client. “We rely on Tata Technologies for their vast and extensive global expertise, and support on various aspects of engineering, which makes them an integral part of our business growth journey," says Anand Kulkarni, chief products officer, head of HV programs and customer service, Tata Passenger Electric Mobility. “As partners, we leverage their technical expertise when it comes to engineering in the mobility domain. Their dependable support is crucial to our business, enabling us to innovate and refine our mobility solutions to meet the fast evolving market demands."

Tata Motors has been the company’s oldest and key client. “We rely on Tata Technologies for their vast and extensive global expertise, and support on various aspects of engineering, which makes them an integral part of our business growth journey," says Anand Kulkarni, chief products officer, head of HV programs and customer service, Tata Passenger Electric Mobility. “As partners, we leverage their technical expertise when it comes to engineering in the mobility domain. Their dependable support is crucial to our business, enabling us to innovate and refine our mobility solutions to meet the fast evolving market demands." The company expects Airbus to be among its top five customers in the next three years and the sector’s revenue contribution to increase to 25 percent.

The company expects Airbus to be among its top five customers in the next three years and the sector’s revenue contribution to increase to 25 percent. As a services player, growth tends to be limited to 15-20 percent, says Saraf of Tusk Investments. “In order to see exponential growth, the company should continue looking at joint ventures outside the Tata group—as with BMW—where they co-invest with clients. I think that is going to be a big game changer."

As a services player, growth tends to be limited to 15-20 percent, says Saraf of Tusk Investments. “In order to see exponential growth, the company should continue looking at joint ventures outside the Tata group—as with BMW—where they co-invest with clients. I think that is going to be a big game changer."