Edtech startup Gradeup's big test

To avoid collision with market leader Byju's, Gradeup has identified a unique niche—competitive exams—currently underserved by the online market. Can it dominate the highly fragmented market?

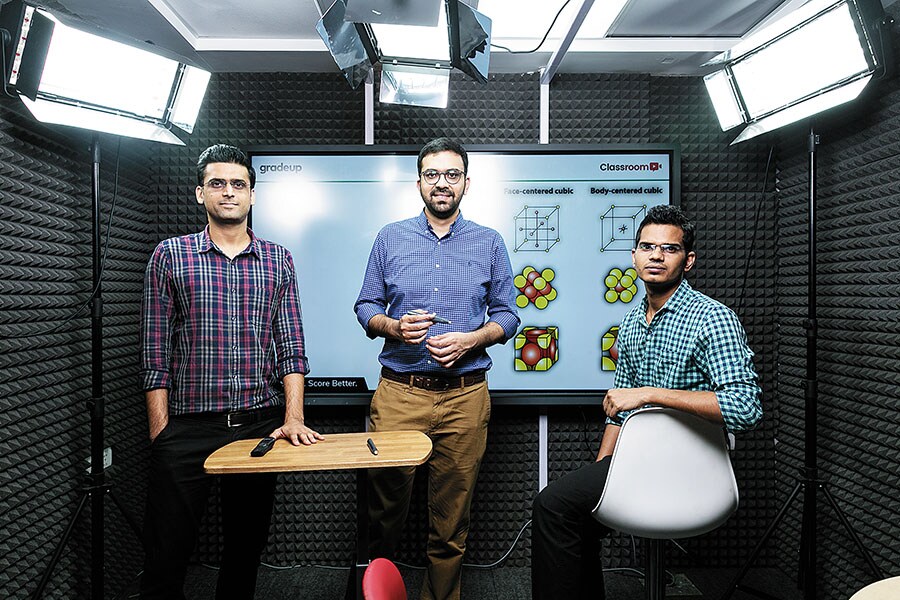

(From left) Gradeup Co-founders Vibhu Bhushan, Shobhit Bhatnagar and Sanjeev Kumar believe that engaging parents will help the latter take online learning seriously

(From left) Gradeup Co-founders Vibhu Bhushan, Shobhit Bhatnagar and Sanjeev Kumar believe that engaging parents will help the latter take online learning seriously

Image: Madhu Kapparath[br]Attending Parent Teacher Meetings (PTM) was a dreaded affair for Shruti Shukla, though she had endured them without a quibble for a decade when her son was in school. At another such meeting in early October, the 45-year-old, who is a chartered accountant with an MNC in Gurugram, hoped against hope that she would not have to hear a recurring snub that often came her way from teachers who did not rate her child highly: That her son Rohit—now 23, and preparing for the Graduate Aptitude Test in Engineering (GATE)—was “good for nothing”.

The online PTM started at 10 am, only to surprise Shukla with the news that her son had scored a distinction in most of his mock examinations. The voice at the other end, that of a teacher from online edutech startup Gradeup, further informed that Rohit’s chances of clearning GATE were high. As she accessed the online report card, Shukla could not have been happier.

An online PTM for undergrads is one of the ways in which Gradeup is trying to stand out in a cluttered online edutech market and an unorganised offline market dominated by mon-and-pop coaching centres. Other differentiation strategies include online live classes, regular intensive mock tests, student feedback about the teachers and a team that closely tracks the progress of every enrolled online student.

Started by three engineer friends—Vibhu Bhushan, Shobhit Bhatnagar and Sanjeev Kumar—in September 2015, Gradeup focusses mainly on competitive exams like JEE (joint entrance examination) for engineering, NEET (national eligibility cum entrance test) for medical colleges, GATE etc, while offering other prep courses including for bank and clerk exams. What also gives it an edge, and enough legroom to grow, is the fact that the startup is not competing with Goliaths like Byju’s that focus on school students.

Unlike other online edutech players that have a battery of sales executives to push business, Gradeup decided to target the stakeholder that still matters most in India: Parents. “We do PTMs once in two weeks,” says Shobhit Bhatnagar, co-founder of Gradeup, who believes that involving parents will help them take the business more seriously. “It not only convinces them but makes it [online learning] much more credible.”

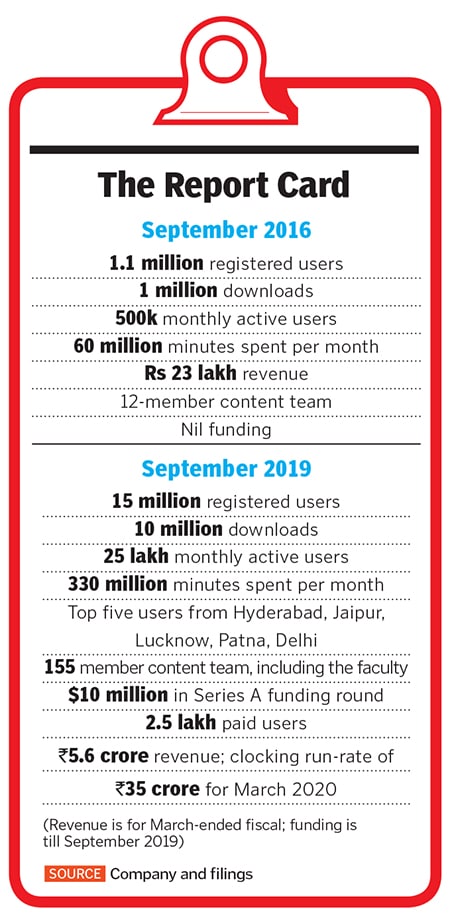

The report card of the four-year-old startup, too, has been impressive. From 1.1 million registered users and a ₹23 lakh revenue after the first year of operations, Gradeup has galloped to 15 million registered users and a revenue of ₹5.6 crore by the end of September this year. What looks most heartening for the startup, which has raised $10 million from Times Internet, is to have over 2.5 lakh paid users. “We don’t offer freebies. What comes free is a few trial classes to begin with,” says Vibhu Bhushan, 34, also a co-founder. “They create stickiness and results in online conversion.”

Two key factors helped the startup. First, the move to target undergrads and above avoided a head-on collision with market leader Byju’s. “In fact, Byju’s has never been our competition. They have done a great job with creating an online education market,” avers Bhatnagar. Second, the blue ocean strategy—to be in a segment with relatively less competition—seems to be paying off. “Gradeup identified a unique niche—competitive exams—which is underserved by the online market,” says Jessie Paul, founder of marketing advisory firm Paul Writer. Given that many aspirants practice full-time for their exams, she explains, a mobile app allows them to study round-the-clock, in addition to providing them access to the best tutors and a huge bank of practice tests. Gradeup’s community approach is also a differentiator as the interface allows for social media-style interactions with the tutors, Paul adds.

Venture capitalists say that Gradeup has massive headroom for growth as it takes a stab at the offline coaching market that is fragmented and yet to be disrupted. “The opportunity is huge in smaller towns due lack of quality preparatory classes,” says Anil Joshi, managing partner at Unicorn India Ventures. The challenge for the startup, he explains, would be to keep the cost of customer acquisition low.

Another potential challenge could be a continuous content upgradation and protection, and right methods of delivery. “Competing in a highly fragmented market with lots of mom-and-pop players and keeping pace with the changing requirements of the curriculum are also key challenges,” says Vikram Gupta, founder and managing partner at IvyCap Ventures, adding that only players that have the perfect combination of content, right technology for delivery and preparation of tests, and a combination of offline and online business model will survive.

Bhushan, for his part, doesn’t intend to take Gradeup offline. If one looks at the hybrid model—whether it’s Lenskart or Urban Ladder or any other online player—their services or products are delivered offline too. “It makes sense for them,” he says. But for a pure-play digital product, he continues, setting up shop is not something that will add substantial value in the long term.

Bhatnagar is more forthright. Without ruling out the possibility of having centres where students could attend class or take semi-assisted tests in the long run, he stresses that the mission of Gradeup is to bring students online first. “An online product must be consumed online, especially when it is better than its offline counterparts,” he smiles.

First Published: Nov 14, 2019, 11:39

Subscribe Now