Back in 2005, the brothers were convinced that batter was the best business option for them. There was a pressing need and huge demand for superior quality of batter. The supply, though, was unreliable and unorganised. The kirana background of the four cousins, who ran a pocket-sized grocery store in Indiranagar in Bengaluru, and the enterprising mindset of the maverick IT professional—Musthafa had a few job stints in Europe, the Middle East and India, including Citibank in Dubai and Intel in Bengaluru—prodded them to take a stab at the problem. They made a humble beginning with a grinder, mixer, sealing machine, weighing scale and a second-hand Scooty, and ended the first year with a modest collection of ₹8 lakh. Over the next three years, the revenue jumped to ₹50 lakh. The business was moving at a brisk pace.

Then came the big Chennai experiment in 2009. iD was selling around 3,500 kg of batter in Bengaluru, and the aspiration was to go to the Mecca of idli-dosa: Chennai. Musthafa moved swiftly, invested all the savings of the company—₹20 lakh—opened a plant in Chennai and launched batter at ₹40 per kilo. The move flopped. Rivals were selling batter at half the rate, some even lower than ₹20 per kg. “Forget profit, their MRP was not even the cost of my raw material," rues Musthafa, who didn’t want to play the price game. After over a year or so, iD exited a profusely bleeding Chennai market.

So, iD stayed confined to Bengaluru, there was no bank money to tide over the crisis, and raising capital was well-nigh impossible. This was a serious problem on the second front. “Idli-dosa was not a fancy business," rues the first-generation entrepreneur who did his MBA from IIM-Bangalore. “If I had started a pizza business after my MBA, many would have invested," he says. The business indeed had a problem in terms of sizing by the venture capitalists (VC). “They were not sure of the size," says Musthafa. With VCs staying away and the founder failing to get money to grow the business, iD was in the midst of a brewing crisis. The batter play was becoming too thick.

Meanwhile, on a breezy evening in Bengaluru, Musthafa was in the thick of action. The carrom game with employees—many were friends, family and relatives from Kerala—was entering into an intense phase. Musthafa was making another attempt to pocket the queen, and yet again he failed. After a few seconds, he again got a chance. He again failed. The brothers knew there was something odd. They glanced at the big player, who looked lost. The salary had been delayed by almost six months. “I was not able to pay the tuition fees of my son," recalls Musthafa, who used to play carrom with his cousins and relatives every day. “It was tough," he says. “I couldn’t pay salaries, and still many stood by me," he says. The camaraderie and the emotional bonding, the founder underscores, is one of the blessings that a village way of life gives you.

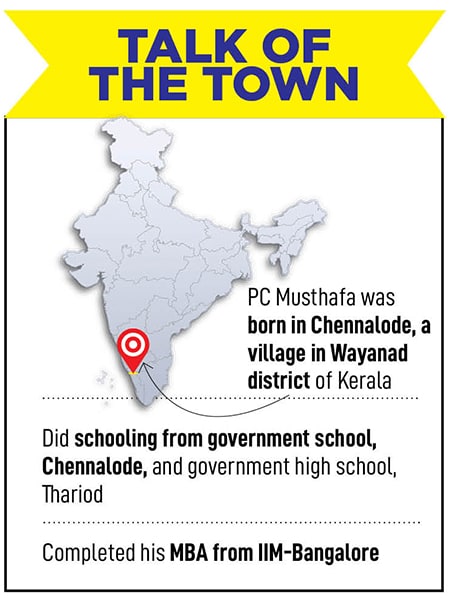

The village way of life, though, was grinding. Musthafa takes us back to his birthplace. Chennalode, a secluded village in the Wayanad district of Kerala, was not an easy place to grow up in. “Back then, there were no roads, no electricity, and no schools," he says. The young boy had to travel six kilometres every day to reach primary school. “The high school was outside the village," he says. Life was difficult for the boy. His father was a daily wage earner and used to work on a ginger farm. “He used to work for 13 hours and earn ₹12 every day," he says. Musthafa’s mother, he underlines, used to skip one meal every day so that there was sufficient food for the kids. The hardship emotionally forced the young lad to work with his father, who defined his role. “I used to uproot the ginger, clean the soil, put it in a bag and load it on my dad’s shoulder. That was my role," he says with a smile. There was a cart, he lets on, on which the produce was loaded and transported to market Years later, in 2007, Musthafa faced a serious transport problem. He started iD with one second-hand Scooty, and later bought another vehicle. On a busy Friday afternoon, the transport vehicle broke down. The driver and the salesman tried to fix it, but failed. The towing vehicle demanded a hefty fee of ₹2,000. “We couldn’t afford it. So taking it was out of question," he recalls. The vehicle remained stranded for hours, and then a sudden realisation hit and the panic set in. Saturday was the best business day for iD. A stuck vehicle meant zero business, and the impact of it would be felt for weeks. Late in the evening, Musthafa reached the spot. “There has to be some way to move this," he thought and hunted for a rope, wire or anything that could help tow the vehicle. There was none, though. Suddenly, his salesman removed his lungi, tied it to the stranded vehicle and took it to the service centre. “Fortunately, he was wearing underwear," says Musthafa, bursting into loud laughter. “The city doesn’t teach you this jugaad way of life. This comes from the village," he says smiling.

![]()

What also comes from the village is a way of life where there are no shortcuts, even if that means paying a hefty price. It was sometime in 2011. Musthafa launched a few side products to shore up sales. One of them was a diamond cut wafery biscuit, which had the shape of a mini samosa. The chilli-flavoured product got an encouraging reception in the market, and demand started growing briskly. Then one day, the founder got a call from one of the big hotels in Bengaluru. The manager made a weird demand. “He wanted to buy thousands of kilos of diamond cuts," recalls Musthafa, adding that the order for a month was more than what iD managed to earn in a year. It was a jackpot, and a God-sent opportunity to tide over the financial blues. The eager entrepreneur went to the hotel, met the chef, and tried to understand how such a huge quantity of product would be consumed.

![]() The diamond was about to lose its sheen. “They wanted to make it a bar snack, and serve it with liquor," says Musthafa. “Should I be promoting my product to sell liquor?" he wondered. The founding team was confused. They discussed, they debated, and they declined the offer. “I felt like crying after refusing to supply," says the founder who was torn between morals and business realities. “Whatever be the cost, I won’t do anything which has a value conflict for us," he says. It was a tough call. iD badly needed money to grow, to pay salaries on time, and to expand its reach. The money was on the table, but Musthafa declined. “I was really on the verge of crying," he says.

The diamond was about to lose its sheen. “They wanted to make it a bar snack, and serve it with liquor," says Musthafa. “Should I be promoting my product to sell liquor?" he wondered. The founding team was confused. They discussed, they debated, and they declined the offer. “I felt like crying after refusing to supply," says the founder who was torn between morals and business realities. “Whatever be the cost, I won’t do anything which has a value conflict for us," he says. It was a tough call. iD badly needed money to grow, to pay salaries on time, and to expand its reach. The money was on the table, but Musthafa declined. “I was really on the verge of crying," he says.

Meanwhile, during his engineering stint at Calicut, the college student did cry once. It was a seminar, and Musthafa had to make a presentation. “I froze. I couldn’t utter a word," he recalls. The huge crowd in the auditorium was stunned. “It was my favourite subject. I had prepared it so well. Yet I couldn’t speak," he says. Musthafa left the room with tears rolling down his face. “I failed but I resolved to become a public speaker one day," he says.

Back in his village, he flunked in class VI. “I was not good at studies. I dropped out of school," he says. On one of the days when he was assisting his father on the farm, he was spotted by his school teacher. “Matthew sir motivated me to go back to school," he says. After that, there was no looking back. He worked hard, improved his ranks, and eventually topped the school. After finishing higher secondary, he saw the world outside of the village. “And after my engineering, I saw a world outside Kerala," he says.

Also read: Can trust be the new currency for iD Fresh Food?

Fast forward to 2021. There was another—and obnoxious—side of the world that Musthafa was about to see. There were social media posts that alleged that iD Fresh had animal extracts in its products. The malicious rumour went viral, the crisis snowballed, and suddenly everything was at stake for the company that had amassed sizeable growth.

In FY21, iD clocked an operating revenue of ₹294 crore, had a wide presence in more than 45 cities, and a retail footprint of 30,000 stores. “The false news was a huge propaganda against iD," says Musthafa, who took a leaf out of his village life in handling the situation. “Every crisis is an opportunity for a village boy," he says, explaining his disruptive move. “We opened up our factory for a live tour and live stream," he says. The trigger to do so, he explains, came from the realisation that the village boy had nothing to lose, and nothing to hide.

![]() The inspiration, though, came from his IIM professor. Back during his MBA days, Musthafa was made to understand the difference between a rat and an elephant in terms of mindset. If a rat has to cross MG Road in Bengaluru, explains Musthafa, nobody will notice, and the rodent will take shortcuts to do it. On the other hand, if an elephant crosses the road, the world will notice. “iD had nothing to hide. Elephants can’t hide," he says. The gambit of being transparent worked, and the crisis was diffused.

The inspiration, though, came from his IIM professor. Back during his MBA days, Musthafa was made to understand the difference between a rat and an elephant in terms of mindset. If a rat has to cross MG Road in Bengaluru, explains Musthafa, nobody will notice, and the rodent will take shortcuts to do it. On the other hand, if an elephant crosses the road, the world will notice. “iD had nothing to hide. Elephants can’t hide," he says. The gambit of being transparent worked, and the crisis was diffused.

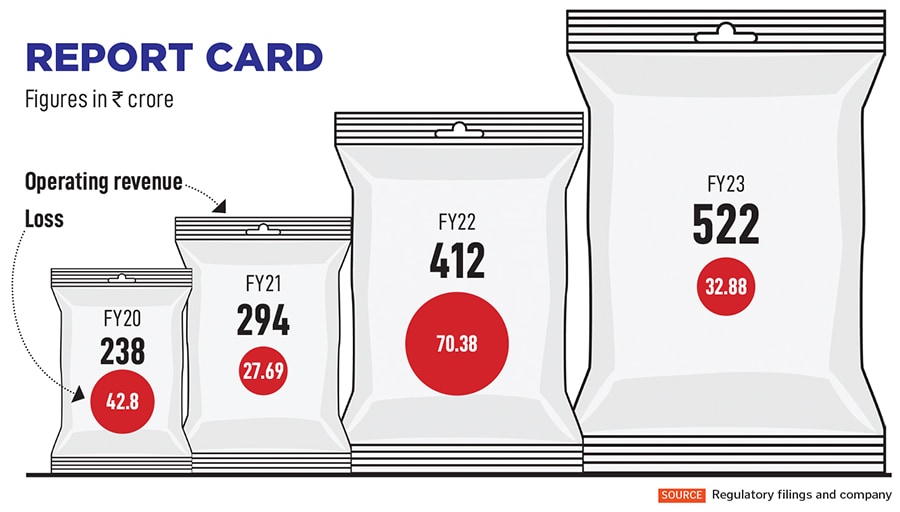

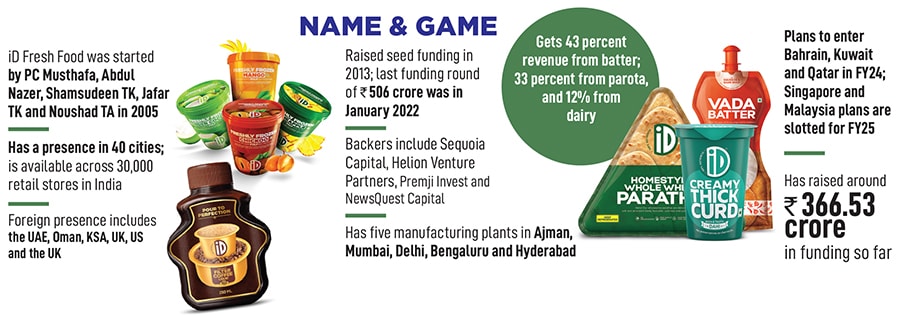

A few quarters later, in 2023, the economics of running a transparent business seems to be handsomely paying off. Let’s look at the report card. From ₹238 crore in FY20, the operating revenue jumped to ₹522 crore in FY23. The losses during the same period came down from ₹42.8 crore to ₹32.88 crore. iD has five manufacturing plants across Ajman, Mumbai, Delhi, Bengaluru and Hyderabad has raised around ₹366.53 crore in funding so far and has backers such as Sequoia Capital, Helion Venture Partners, Premji Invest and NewsQuest Capital. In terms of revenue distribution, around 43 percent comes from batter, 33 percent from parota, and 12 percent from dairy. The company now plans to enter Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar over the next few months. In terms of manufacturing prowess too, iD has morphed into a batter goliath. Around 1.1 lakh kilos of idli-dosa batter, and 4 lakh parotas are made every day (see box).

![]()

Frugality, reckon funding gurus, is one of the biggest weapons of most of the founders from small towns. Take, for instance, iD. A loss of just ₹32.88 crore is peanuts as compared to the bulging bottomlines of most consumer product startups. “Most of them have come from a background where resources were scarce," says Rahul Chowdhri, partner at Stellaris Venture Partners. They have a great understanding of value propositions and have a value-conscious mindset. “The values also get reflected in employee relations and the understanding that they have," he adds.

Musthafa, for his part, lists out three attributes from life in a village that have become a part of his DNA. “Values, humility and jugaad… earning money the right way and for a right cause is extremely crucial," he maintains. A tree, he underlines, laden with fruit will always bend low. “This is what your village and your family teaches," he signs off.

The bombing of the Chennai experiment had another devastating collateral damage. iD started losing ground on the home turf, Musthafa didn’t have any capital to expand, and the option of taking a bank loan was never an option to begin with. Musthafa explains. “We don’t pay interest, we don’t take interest. It’s against our ethical values," he says. EMIs, he adds, are one more reason to shun any kind of loan, and kill creativity in individuals and businesses.

The bombing of the Chennai experiment had another devastating collateral damage. iD started losing ground on the home turf, Musthafa didn’t have any capital to expand, and the option of taking a bank loan was never an option to begin with. Musthafa explains. “We don’t pay interest, we don’t take interest. It’s against our ethical values," he says. EMIs, he adds, are one more reason to shun any kind of loan, and kill creativity in individuals and businesses.

The diamond was about to lose its sheen. “They wanted to make it a bar snack, and serve it with liquor," says Musthafa. “Should I be promoting my product to sell liquor?" he wondered. The founding team was confused. They discussed, they debated, and they declined the offer. “I felt like crying after refusing to supply," says the founder who was torn between morals and business realities. “Whatever be the cost, I won’t do anything which has a value conflict for us," he says. It was a tough call. iD badly needed money to grow, to pay salaries on time, and to expand its reach. The money was on the table, but Musthafa declined. “I was really on the verge of crying," he says.

The diamond was about to lose its sheen. “They wanted to make it a bar snack, and serve it with liquor," says Musthafa. “Should I be promoting my product to sell liquor?" he wondered. The founding team was confused. They discussed, they debated, and they declined the offer. “I felt like crying after refusing to supply," says the founder who was torn between morals and business realities. “Whatever be the cost, I won’t do anything which has a value conflict for us," he says. It was a tough call. iD badly needed money to grow, to pay salaries on time, and to expand its reach. The money was on the table, but Musthafa declined. “I was really on the verge of crying," he says. The inspiration, though, came from his IIM professor. Back during his MBA days, Musthafa was made to understand the difference between a rat and an elephant in terms of mindset. If a rat has to cross MG Road in Bengaluru, explains Musthafa, nobody will notice, and the rodent will take shortcuts to do it. On the other hand, if an elephant crosses the road, the world will notice. “iD had nothing to hide. Elephants can’t hide," he says. The gambit of being transparent worked, and the crisis was diffused.

The inspiration, though, came from his IIM professor. Back during his MBA days, Musthafa was made to understand the difference between a rat and an elephant in terms of mindset. If a rat has to cross MG Road in Bengaluru, explains Musthafa, nobody will notice, and the rodent will take shortcuts to do it. On the other hand, if an elephant crosses the road, the world will notice. “iD had nothing to hide. Elephants can’t hide," he says. The gambit of being transparent worked, and the crisis was diffused.