From the likes of the flamboyant Vijay Mallya of the ill-fated Kingfisher Airlines to the cautious and wily Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways, and the blue-blooded Nusli Wadia of Go First, India’s skies have a history of bringing death knell to many. Some of that, of course, was their own doing with ill-advised and irrational business propositions, but the turbulent skies have had their fair share. Today, Mallya is a fugitive, Goyal is languishing in jail and Wadia is banking on his real estate empire to keep his Bombay Dyeing empire running."¯

Then there are those like deceased billionaire Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, who braved the brouhaha to bet on the Indian skies only to face severe turbulence later. Akasa is currently fighting tooth and nail against some of its pilots who have left the airline en masse, disrupting the airline’s operations and hitting its market share considerably. Akasa was one of the world’s fastest-growing airline after starting in 2022 before disruptions hit the airline in September.

That’s why it’s not surprising that the number of airlines in India has been steadily declining even though the country will likely add 2,000-odd aircraft in the next 20 years. Consider this: Five years ago, India’s skies boasted Jet Airways, Air India, Vistara, AirAsia India, Go First, SpiceJet, TruJet, Zoom Air and Air Deccan. Five years later, the Tata group, with all its financial might behind it, will cut down four airlines that it owns into two. The Tata group will operate Air India and Air India Express after it bought Air India from the government and brought three other airlines into its fold, including Vistara, AirAsia India and Air India Express."¯

The Nusli Wadia-owned Go First has shut down operations, and so has Jet Airways, while SpiceJet is on a wing and a prayer with dwindling market share. Air Deccan, Zoom Air, and TruJet are history too. Two regional airlines, Star Air and Fly Big ferry, carry minuscule passengers annually."¯

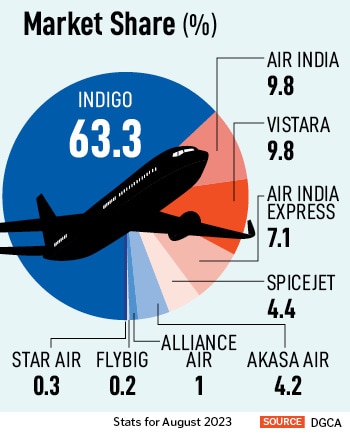

The lone exception to all this frenzy is IndiGo, the country’s largest airline with a 63 percent market share, and over 300 aircraft in its fleet, flying both domestic and international routes. Of the 10 crore passengers who took to the skies between January and August, six crore took IndiGo alone, a remarkable feat considering the airline started around the same time as SpiceJet and Go First. Of the remaining, 2.56 crore took airlines operated by Air India. Together, Air India and IndiGo ferried over 8.5 crore passengers."¯

![]() In effect, that only means one thing. India’s aviation sector is moving into something of a duopoly. With IndiGo having a market share of 63.3 percent and Air India Group having another 25.7, the two airline companies corner 89 percent of the domestic market. “This duopoly has emerged at a time when the market dynamics are quite volatile," says Satyendra Pandey, managing partner, aviation services firm AT-TV. “As of now, the country has two airlines that are in separate stages of the insolvency process a startup airline coming up on one year of operations and an airline that is sourcing significant funds from the Emergency Credit Loan Guarantee Scheme."

In effect, that only means one thing. India’s aviation sector is moving into something of a duopoly. With IndiGo having a market share of 63.3 percent and Air India Group having another 25.7, the two airline companies corner 89 percent of the domestic market. “This duopoly has emerged at a time when the market dynamics are quite volatile," says Satyendra Pandey, managing partner, aviation services firm AT-TV. “As of now, the country has two airlines that are in separate stages of the insolvency process a startup airline coming up on one year of operations and an airline that is sourcing significant funds from the Emergency Credit Loan Guarantee Scheme."

It’s into this mix that Indigo and Air India, both well-funded and well-managed airlines with strong market shares, are flexing their muscles, considering how they are ramping up on aircraft purchases and launching new routes. “Inevitably, stakeholders will gravitate to do business with stronger airlines which then translates to competitive dynamics and consequences for consumers," adds Pandey. IndiGo and Air India have placed orders for nearly 1,000 aircraft this year, from both Boeing and Airbus."¯

“India"s market is brutal and tough to make money unless the airline has scale, is nimble, and very hard-nosed in cost control," says Shukor Yusuf, head of Malaysia-based aviation consultancy Endau Analytics."¯

Flying into a duopoly

Duopolies aren’t alien to India. In the telecom sector, Airtel and Jio have a combined market share of about 80 percent, making the sector a near-duopoly. The same extends to the taxi-hailing segment with Ola and Uber, in the food delivery business with Swiggy and Zomato, and the ecommerce sector with Flipkart and Amazon. In a duopoly, two firms dominate the market, leaving customers with little choice, while also dictating pricing."¯

The aviation sector, however, wasn’t designed to become a duopoly. Flying in India had largely remained a state-controlled activity until the government decided to open up the sector as part of its new economic policy in 1991. Soon enough, new entrants flocked to the sector, including the likes of Jet Airways, Damania Airways, East-West Airlines, ModiLuft and Air Sahara, apart from the already-existing Air India and Indian Airlines. Of this, ModiLuft was started as a partnership between industrialist SK Modi and German flag carrier Lufthansa."¯

Within a decade, though, many of them folded up with only Jet Airways and Air Sahara surviving the onslaught. The next decade saw a flurry of activity from low-cost carriers, partly startled by the collapse of full-service carriers and looking to emulate the success of Air Deccan, a low-cost carrier that in many ways allowed millions to take to the skies with its cheaper ticket prices. The new entrants included SpiceJet, IndiGo and Go First, while Kingfisher Airlines, backed by Mallya, also forayed as a full-service carrier."¯

“The Indian aviation market has always struggled with high costs, as it is not considered a necessity but a luxury service," says Alok Anand, chairman and CEO of Acumen Aviation, an aircraft asset management and leasing company. “While this has changed to a certain extent, the cost base has only gone up, not to forget ATF charges (taxes on ATF rationalised recently to a large extent), and airport-related charges." ATF accounts for about 45 percent of an airline’s operating cost, while airport charges account for another 5 percent usually."¯

Then there is also the lack of operational and technical efficiency, along with ill-timed business decisions in addition to the challenges of India’s compliance and regulatory burden. “As a result, very few could survive the true grind of building an airline," Anand says. Instances of ill-timed business decisions include those such as Jet Airways" acquisition of Sahara, Air India’s merger with Indian Airlines and Kingfisher’s acquisition of Air Deccan, which eventually led to operational troubles and mounting debt for the acquirers."¯

![]() From the likes of the flamboyant Vijay Mallya of the ill-fated Kingfisher Airlines to the cautious and wily Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways, India’s skies have a history of bringing death knell to many.Image: Getty Images

From the likes of the flamboyant Vijay Mallya of the ill-fated Kingfisher Airlines to the cautious and wily Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways, India’s skies have a history of bringing death knell to many.Image: Getty Images

“Kingfisher and Jet Airways both are examples of how crony capitalism could generate artificial success and then eventual downfall when market forces catch up," adds Anand. In 2008, Jet Airways and Kingfisher together accounted for 60 percent of the domestic market, indicating how quickly the tables turn in one of the world’s fiercest aviation markets."¯

“There is a combination of reasons, including failure to address structural challenges within the aviation industry," Pandey of AT-TV says about why the sector is now staring at a duopoly. “Structural costs, including the cost of capital, fuel taxes and airport charges, continue to be high. A desire to force-fit business models from the West continues. And the sector continues to be taxed as a luxury and regulated as a commodity. Training, technology and tourism all have to be adequately integrated into the overall ecosystem."

Of course, there were external factors too as Go First, which recently shut down, claims. The Mumbai-headquartered airline claims that it had to file for bankruptcy after being forced to ground its aircraft over faulty engines made by American engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney. The GTF engines developed by Pratt & Whitney were found to have problems with fan blades, an oil seal, and the combustion chamber lining, leaving the airline with only 50 percent of its fleet to fly with, costing it $1.3 billion in lost revenues."¯

The sector was also hard hit by the onset of Covid-19, which grounded airlines globally. In India, ratings agency ICRA believes that airlines, both private and public, had a combined loss of between Rs11,000 crore and Rs13,000 crore in the last fiscal, while that number stood at Rs23,500 crore in the year before that, largely due to disruptions caused by Covid-19. In the current fiscal, losses in the sector are expected to be between Rs5,000 crore and Rs7,000 crore according to ICRA."¯"¯

Also read: The Air India of today isn"t the Air India of tomorrow: Campbell Wilson

The new reality

Meanwhile, with almost 90 percent of the market firmly under their control, IndiGo and Air India will have the distinct advantage of shaping up the sector over the next few years. “In the near term, airfares are likely to remain at elevated levels," says Pandey. “Also in the near term, some routes will see limited competition. But as the airlines expand, it is assumed that market forces will take over."

Air India is in the midst of a transformation, after being acquired by the Tata group in 2021. The airline is now looking to create two arms, Air India, a full-service carrier comprising Vistara, and a low-cost airline, Air India Express comprising AirAsia India and Air India Express. India’s domestic aviation market is currently led by low-cost carriers that control as much as 80 percent of the market. The Tata group’s total fleet size stands at 235, including Air India’s 121 aircraft, AirAsia India’s 28, Vistara’s 60 and Air India Express’ 26 jets."¯"¯

![]() According to a turnaround plan at Air India, the airline has set itself clear milestones focussed on growing its network and fleet, developing a revamped customer proposition, improving reliability and on-time performance, and taking a leadership position in technology, sustainability and innovation, while aggressively hiring industry talent. Over the next five years, the airline will also look to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market. Already, it has invested $400 million in completely new interiors for the airlines’ existing wide-body aircraft, new seats and new in-flight entertainment in addition to spending another $200 million on IT infrastructure."¯

According to a turnaround plan at Air India, the airline has set itself clear milestones focussed on growing its network and fleet, developing a revamped customer proposition, improving reliability and on-time performance, and taking a leadership position in technology, sustainability and innovation, while aggressively hiring industry talent. Over the next five years, the airline will also look to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market. Already, it has invested $400 million in completely new interiors for the airlines’ existing wide-body aircraft, new seats and new in-flight entertainment in addition to spending another $200 million on IT infrastructure."¯

“India has seen a fairly regular cycle of some airlines not making it," Campbell Wilson, CEO of Air India, had told Forbes India. “But in the past that was also true of the US and Europe. So perhaps some form of consolidation of the industry is required for the industry to become healthy and stable and have the platform to grow."

In the process, the airline is also expected to wrestle for dominance from IndiGo in the domestic market, while IndiGo will look to topple Air India on international routes. On international routes, Air India has a 23 percent market share, while IndiGo has 15.78 percent. “I would say that Air India is not yet close to the operational efficiency of IndiGo, but its deep pockets and right intentions to execute will get it there in a few years," adds Anand. “Interestingly, IndiGo’s fares are comparatively the same, meaning that Air India is possibly selling at an operating loss for market share."

Air India though has already laid the groundwork, looking to replicate IndiGo’s success in its timely performance, staff behaviour and young fleet, as it looks to stage a turnaround in its fortunes. The Tata group wants to take on IndiGo with free meals, entertainment and frequent flyer programmes, which could take away flyers due to the value proposition. In the process, it also expects its low-cost arm to emerge as a feeder for its international operations. A growing middle class in the world’s fastest-growing large economy, alongside growing credit penetration and rising incomes will push demand for full-service carriers.

“Adequate capitalisation and expansion are critical to compete with the market leader," adds Pandey. “However, that is easier said than done. In the final analysis, it is a combination of the right cost base and capturing a share of the consumer"s wallet that will lead to success."

IndiGo too has been aggressively pushing its growth plans. In June, the airline beat Air India to what’s now referred to as the mother of all aviation deals when it announced a firm order of 500 A320 family aircraft from Airbus. The deal is currently the biggest single purchase agreement in the history of commercial aviation and would mean the airline will now have 1,330 aircraft on order from Airbus, making it the world’s biggest A320 family customer.

It also helps that the company is adequately funded, having built up a massive cash reserve over the past decade. On August 2, IndiGo announced its highest-ever profit for a quarter when it announced its April-June quarter results. The Gurugram-headquartered airline’s net profit stood at a staggering Rs3,089 crore against a loss of Rs1,056.5 crore in the year-ago period. Revenues, meanwhile, swelled to Rs17,160 crore during the quarter, its highest ever, while cash reserves stood at over Rs27,000 crore."¯

“It is an uphill task for Air India and includes getting to the right cost base while also working on a network restructuring, integration between airlines, expansion, product refresh, pricing, schedules," says Pandey."¯

The tussle between Air India and IndiGo aside, does the emerging market dynamic mean that millions of passengers will be stuck with the two dominant players or will new players look to foray? “Opportunity exists, but the barriers to entry have only become stronger," says Pandey. “Financing is hard to come by and given the history of failures in the sector and challenges with the Jet Airways and Go First revival, investors continue to be wary of the sector. Aviation continues to be a sector with razor-thin margins and India’s airlines have to develop business models that are aligned to market realities and not based on models that are copied from the West.""¯

Then, there are others like Akasa, who believe that there is an opportunity for new entrants. Vinay Dube, the airline"s CEO, likens his airline to US-based Alaska Airlines, which, he says, has withstood the might of an oligopolistic market condition in the US—United, American, Southwest and Delta corner over 80 percent of the market. “But it has some of the happiest employees, customers and shareholders as a whole," Dube told Forbes India earlier."¯Hence, we"re not worried about what the others are doing. India is a market where you can have multiple airlines thrive if they"re run properly. And we"re just focusing on running a good proper airline."

So, is the duopoly in the skies here to stay? “I think the duopoly situation is a snapshot of time which will change as time passes," says Anand. “Especially if SpiceJet can manage to revive fully, and given its very interesting cargo operations too. Akasa and other (regional) carriers will play an important role in providing more choice to consumers. The high growth trend is an indication of the times ahead, but it will surely have cycles of growth and bust as in every aviation market, especially because aviation is highly influenced by global affairs. India’s success in aviation can be fully realised only if a holistic ecosystem of airlines and support services can be fully deployed, which at the current rate is a 5-10 year project."

In effect, that only means one thing. India’s aviation sector is moving into something of a duopoly. With IndiGo having a market share of 63.3 percent and Air India Group having another 25.7, the two airline companies corner 89 percent of the domestic market. “This duopoly has emerged at a time when the market dynamics are quite volatile," says Satyendra Pandey, managing partner, aviation services firm AT-TV. “As of now, the country has two airlines that are in separate stages of the insolvency process a startup airline coming up on one year of operations and an airline that is sourcing significant funds from the Emergency Credit Loan Guarantee Scheme."

In effect, that only means one thing. India’s aviation sector is moving into something of a duopoly. With IndiGo having a market share of 63.3 percent and Air India Group having another 25.7, the two airline companies corner 89 percent of the domestic market. “This duopoly has emerged at a time when the market dynamics are quite volatile," says Satyendra Pandey, managing partner, aviation services firm AT-TV. “As of now, the country has two airlines that are in separate stages of the insolvency process a startup airline coming up on one year of operations and an airline that is sourcing significant funds from the Emergency Credit Loan Guarantee Scheme."

According to a turnaround plan at Air India, the airline has set itself clear milestones focussed on growing its network and fleet, developing a revamped customer proposition, improving reliability and on-time performance, and taking a leadership position in technology, sustainability and innovation, while aggressively hiring industry talent. Over the next five years, the airline will also look to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market. Already, it has invested $400 million in completely new interiors for the airlines’ existing wide-body aircraft, new seats and new in-flight entertainment in addition to spending another $200 million on IT infrastructure."¯

According to a turnaround plan at Air India, the airline has set itself clear milestones focussed on growing its network and fleet, developing a revamped customer proposition, improving reliability and on-time performance, and taking a leadership position in technology, sustainability and innovation, while aggressively hiring industry talent. Over the next five years, the airline will also look to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market. Already, it has invested $400 million in completely new interiors for the airlines’ existing wide-body aircraft, new seats and new in-flight entertainment in addition to spending another $200 million on IT infrastructure."¯