From Darryl Green at Tata Tele Services to Raymond Bickson at the Indian Hotels Company Limited, the group had attracted some of the most prominent names in the world of business. Yet, none of them in recent memory has managed the impact that Guenter Butschek, the former CEO of Tata Motors, had built in his time.

In his nearly five years at the helm of Tata Motors, and most recently as a consultant till his term ends in March 2022, the German businessman had played a critical role in the resurgence of the automaker from being a fleet taxi operator to India’s third-largest carmaker. Today, Tata Motors’ range of vehicles, from the Harrier to the Altroz and Nexon, has ensured that personal buyers are once again flocking to Tata dealerships compared to a decade ago when the carmaker had fallen out of choice.

The 51-year-old Ilker Ayci, the recently-appointed CEO of Air India, also comes at a time when the country’s aviation sector has been hit hard by headwinds following the nearly two-year Covid-induced shutdown. The aviation industry is likely to see debt levels balloon to some Rs 1.2 lakh crore in the current year, according to the credit rating agency, ICRA.

Ayci is joining Air India from Turkish Airlines, where he served as the chairman for nearly seven years, a period during which the airline increased its fleet size and destinations covered, and even battled the meltdown in the aviation sector without any support from the Turkish government. In fact, the airline diverted much of its attention to cargo operations to stay afloat, a move that helped it post profits at a time when many of its compatriots have been struggling.

In the first nine months of 2021, under Ayci’s leadership, Turkish Airlines posted a net profit of $735 million. “If you are in the airline business, you need to have contingency plans to be well prepared against any challenges," Ayci had said in an interaction with the Global Business Travel Association. Turkish Airlines had announced early in 2020 that it didn’t foresee sacking of employees until the end of 2021. By end of last year, the airline had also announced a 60 percent increase in salaries for employees in the first half of 2022, followed by another 5 percent in the second half of 2022.

“We managed to post a profit at a time when other airlines, such as Lufthansa, Air France-KLM, and United Airlines recorded significant losses," Ayci said in November 2021, according to local newspaper The Hà¼rriyet Daily News. “We recovered from the fallout from the pandemic faster than other airliners."

During the nine months between January and September, Turkish Airlines" revenues stood at $2.37 billion while revenues from the cargo operations amounted to $969 million. Revenues hit almost 85 percent of the figures in 2019. Much of that, Ayci, a friend of the Turkish president Recep Tayyip ErdoÄŸan, believed were due to effective management of resources, and capacity planning even though his chief rivals, including Lufthansa and Emirates, had received support from their government.

![]() Ayci’s immediate task will be to bring the Air India back to profitability

Ayci’s immediate task will be to bring the Air India back to profitability

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Turbulence ahead

India isn’t alien to Ayci, although it is his first stint in the country.

During his time at Turkish Airlines, the 51-year-old had rightly acknowledged the massive potential underlying the Indian aviation market where over 1,900 aircraft are needed in the next 20 years to keep up with the growing demand for air travel. Aircraft manufacturer Airbus projects the 20-year traffic growth of India’s civil aviation sector at 7.7 percent, almost twice the world average of 4.3 percent. Domestic traffic growth is expected at 8.2 percent, one of the world’s highest.

“India and China—both closed markets with certain obstacles such as obtaining flight rights –are expected to dominate half the global markets in the next decade, so we must have a presence there if we wish to be a global company in the future," Ayci, while speaking about Turkish Airlines, said in 2017.

Now that he has joined Air India, Ayci’s immediate task will be to bring the airline back to profitability while also building the airline into what Ratan Tata, the chairman of Tata Sons, calls an airline of choice for both the domestic and international travellers. That will be a humongous task considering the airline has struggled with poor inflight experience, flight delays, and mediocre customer experience.

“I am delighted and honoured to accept the privilege of leading an iconic airline and to join the Tata group," Ayci said on February 14 after being appointed the CEO of Air India. “Working closely with my colleagues at Air India and the leadership of the Tata group, we will utilise the strong heritage of Air India to make it one of the best airlines in the world with a uniquely superior flying experience that reflects Indian warmth and hospitality."

![]() That means, ahead of him lies the challenge of expanding routes, improving horrid inflight services, refurbishing airlines, and even upgrading audio-visual entertainment and other hardware on board, in addition to improving cabin crew practices. Another concern could be the resistance from the various unions of Air India, especially since the Tata group has the freedom to let go of employees hired in the past after a year.

That means, ahead of him lies the challenge of expanding routes, improving horrid inflight services, refurbishing airlines, and even upgrading audio-visual entertainment and other hardware on board, in addition to improving cabin crew practices. Another concern could be the resistance from the various unions of Air India, especially since the Tata group has the freedom to let go of employees hired in the past after a year.

“The immediate task will be to bring together a top-level leadership team who will then be instrumental in undertaking all the restructuring," says Jitender Bhargava, a former executive director at Air India and the author of The Descent of Air India. “It is important to bring best practices to the company and bring it on par with how many of the airlines are run globally. Ayci will certainly be aware of all the changes taking place in the industry and that will help bring standard airline practices and reengineer existing practices in the company."

In his time as the chairman of Turkish Airlines, Ayci had also overseen the expansion of Turkish Airlines to nearly 70 new airports and 20 new countries and saw a nearly 50 percent jump in the fleet size at the airline. The airline also undertook a mammoth shift, which it termed the “great move", under Ayci’s watch when in 2019 it moved its entire operations from Istanbul"s old airport to its swanky new airport in 41 hours. Turkish Airlines had also changed its crew uniform in 2018 under Ayci’s leadership.

Born in Istanbul in 1971, Aycı graduated from Bilkent University in 1994 and worked as a consultant to Turkish president Erdoğan, who was the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality mayor at the time. Later, Ayci went on to graduate from the Marmara University in 1997 in International relations. By 2005, he became a senior manager in Basak Sigorta A.S. (General Insurance Company) and then in Gunes Sigorta AS, an insurance services company between 2006 and 2011.

In January 2011, he was appointed as the Chairman of The Republic of Turkey Investment Support and Promotion Agency, the official organisation for promoting Turkey’s investment opportunities. That stint was soon followed by his as the vice president of the World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies. In 2015, Ayci took over as chairman of Turkish Airlines after serving on its Board of Directors for only a year. He was later appointed as its chairman, a position he held until he resigned in January 2022.

“With Air India, as with any customer-facing business, the experience is paramount and that had been missing for many years" says Vinamra Longani, head of operations at Sarin & Co, a law firm specialising in aircraft leasing and finance. “The Tatas will be looking for someone who can build back the legacy that JRD Tata had built. There aren’t many in India who have managed to run an airline as large as Air India with its own set of problems. Ilker brings that to the table with his experience at Turkish Airlines, especially when it comes to bringing back the experience, managing the union, and dealing with government regulations."

![]() JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group

JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group

Image: Mukesh Parpiani / Dinodia Photo

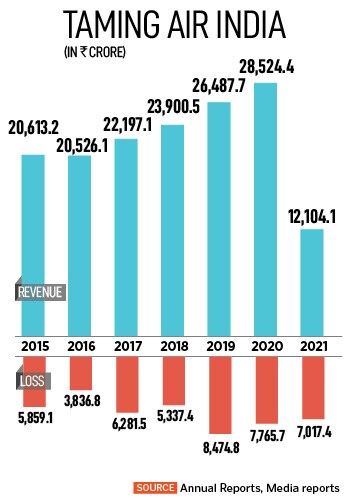

Taming Air India

Air India has returned to the Tata Group after 68 years. JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group, had founded Air India in 1932 before the government took over the airline in 1953 as part of a nationalisation plan. The government purchased a majority stake in the carrier from Tata Sons though its founder JRD Tata continued as chairman till 1977. The company was renamed Air India International Limited, and the domestic services were transferred to Indian Airlines as a part of a restructuring.

Since then, the airline had become a white elephant and even came to symbolise everything wrong with governmental interference in running the day-to-day operations of a company. Much of that is largely due to an ill-timed move by the Indian government in 2007 when it merged Air India—then flying internationally—with domestic carrier Indian Airlines in 2007, creating a bigger entity, the National Aviation Company of India Ltd. Both Air India and Indian Airlines were making losses at that time, bleeding Rs 541 crore and Rs 240 crore, respectively, in 2007.

The merged company had more than 30,000 employees—256 per plane—in 2007, twice the global norm. The national carrier then went on to spend almost one-fifth of its revenue on employee pay and benefits while other airlines traditionally spend only about one-tenth. Besides, the 2008 global economic collapse threw operational expenses out of gear when oil prices skyrocketed. As more private airlines took to flying on routes that once belonged to Air India, business plummeted.

![]() That meant, over time, the airline raked up a debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021 and was steadily losing money on operations. In addition, Air India"s total employee count stands at around 12,500 personnel, while its wage bill for the fiscal year 2021 stood at around Rs 3,000 crore. This means a per employee cost of Rs 24 lakh. In comparison, IndiGo"s India"s largest airline operates a lean model with per employee cost at Rs 14 lakh, some 70 percent lower than Air India.

That meant, over time, the airline raked up a debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021 and was steadily losing money on operations. In addition, Air India"s total employee count stands at around 12,500 personnel, while its wage bill for the fiscal year 2021 stood at around Rs 3,000 crore. This means a per employee cost of Rs 24 lakh. In comparison, IndiGo"s India"s largest airline operates a lean model with per employee cost at Rs 14 lakh, some 70 percent lower than Air India.

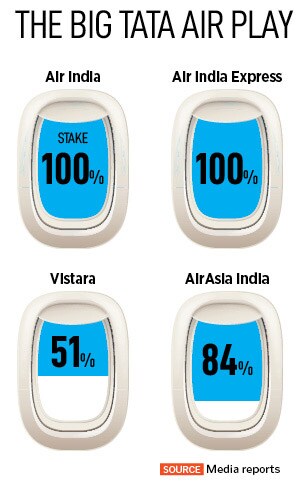

Since coming to power in 2014, the Narendra Modi government had made multiple attempts to sell the airline to private companies, before managing to successfully complete it in October last year. As part of its bid, the Tata group’s wholly-owned subsidiary Talace Pvt Ltd put an enterprise value (EV) bid at Rs 18,000 crore with debt to be retained at Rs 15,300 crore and a cash component of Rs 2,700 crore. Tata’s bid was higher than the Ajay Singh-led consortia"s enterprise value (EV) bid at Rs 15,100 crore. Tatas took 100 percent control of Air India, the low-cost carrier AI Express, and Air India’s 50 percent stake in ground handling firm AI-SATS.

Today, the airline has a fleet of 117 wide-body and narrow-body aircraft, while Air India Express has a fleet of 24 narrow-body aircraft. More than two-thirds of Air India’s consolidated revenues come from the international market even though the airline is India’s second-largest domestic airline. Air India has a market share of 12 percent in the country.

“Since international markets will obviously return more slowly than domestic, this will impede the recovery of Air India versus the large LCCs that are more focussed on short-haul routes," aviation consultancy firm CAPA said in a report. “And when international travel does rebound, Air India will no doubt be confronted once again by strong competition from overseas airlines in India’s international markets."

Air India, which holds a distinct advantage on the international routes largely due to its ability to fly nonstop to cities in the US and Europe, meanwhile, will also face stiff competition from domestic airlines that have begun to push the pedal on international ambitions. Between October and December 2019, before the pandemic disrupted global travel, IndiGo held a near 13 percent among Indian carriers plying on international routes, while Air India and Air India Express held 18.8 percent of the total passengers carried. In all, Indian carriers accounted for 39 percent of passengers flying in and out of the country.

“The basics have to be fixed," adds Longani. “For the Tata group, this is a multi-billion bet and for the foreseeable future, they will lose money. But it’s their way of paying tribute to JRD Tata."

In addition, there is still no clarity on how the Tata group intends to integrate all its airlines.

Tatas have four airlines in their group now. These include two full-service airlines in Air India and Vistara and low-cost carriers AirAsia India and AI Express. Vistara is a joint venture partnership with Singapore Airlines where the airline is a 49 percent stakeholder. The collective entity of Air India, Vistara, and Air Asia has a market share of 25.2 percent, compared to over 54 percent held by Gurugram-based IndiGo.

“The Tata Group got a good deal on Air India when the equity portion of its bid is considered," the CAPA report says. “But the airline also comes with a significant debt load. A return to profitability is unlikely until international demand fully recovers, and after that, it will depend on what changes Tata brings to the airline’s strategy and business model."

That means Ayci and his team will now have to decide on the focus of the airline, especially with the wider group interest at the centre. “The new owner will have to determine what the international and domestic focus will be for Air India, as well as for the other airlines it partly owns. This will help guide its post-pandemic international network and fleet plans," the CAPA report adds. “Another factor will be whether the Tata Group wants to keep pace with the ambitious fleet growth plans of its Indian rivals in order to preserve market share – which will be particularly tempting in the domestic LCC market."

“The turnaround will be one of the most challenging in the history of Indian civil aviation," adds Longani. “The way I see it is that eventually, Vistara and Air India will become one entity since their interests are the same while Air India Express and Air Asia India will function as one entity.""‹

How Butschek found success

Meanwhile, it also won’t be smooth sailing for Ayci either.

In the past, expatriate CEOs, including Darryl Green, Raymond Bikson, and Karl Slym, who had joined the Tata Group hadn’t been entirely successful. While Green quit after a two-year stint in Tata teleservices, Bikson’s tenure of over ten years saw Indian Hotels Company Limited’s debt swell. Between 2004 and 2014, IHCL’s net profit fell from Rs 61 crore to a loss of Rs 590 crore. Meanwhile, Slym, who took over as the CEO of Tata Motors had died by suicide in 2014 after a two-year stint, without much to show at the automaker.

That’s why Guenter’s stint at Tata Motors stands out. “When I joined, our product portfolio was possibly not the most attractive one," Butsheck had told Forbes India earlier. “We were not known to lead launches. Some even concluded we had an outdated portfolio, while others were consistently bringing in modern products. We were under huge pressure because of lots of new launches by rivals. At the same time, we saw huge pressure on the contribution margin. Even Ebitda was negative. It was clear we needed to change the strategic direction. We needed to take a call on whether the business is sustainable and viable."

Butschek had come to India with a reputation for restructuring companies to improve productivity and profitability. Between 2002 and 2005, as president and CEO of Netherlands Car BV, a joint venture between Daimler and Mitsubishi Motors Corporation (in 2012, Dutch coach maker VDC acquired the company and renamed it VDL Nedcar), Guenter was instrumental in its turnaround.

Under Guenter’s leadership, the company decided to shift its entire product offering on two platforms (a design architecture that includes the underfloor, engine compartment, and the frame of a vehicle): Omega, developed by JLR and used in its wildly popular models Discovery and Alfa, which was developed in-house. Having two platforms helped in reducing development and manufacturing costs, unlike earlier when there were multiple platforms for various models.

Then, there were the complicated layers of management that Tata Motors was infamous for. There were, Butschek says, 14 layers that affected overall productivity. The company brought that down to five, to ensure a lean structure and faster communication. The company also ensured there was a renewed focus on safety in vehicles. In 2018, the company’s hatchback, Tata Nexon, became the first made-in-India, sold-in-India car to achieve Global NCAP’s coveted five-star crash test rating. In 2020, the Altroz also received a five-star rating from NCAP.

Butscheck’s success also means the Tata group has the potential to identify those with the ability to turn around fortunes. “You must have faith in the Tatas," adds Bhargava. “They must have done adequate due diligence. For an airline that has suffered because of moribund management, and poor work practices, the challenges are huge, especially with massive daily losses. But the goodwill that Air India and the Tatas have should go a long way in its turnaround."

For decades, Air India has been hit by some heavy turbulence. Now, with Ayci and the Tatas at the cockpit, it’s time to fly out of it.

Ilker Ayci, CEO, Air India

Ilker Ayci, CEO, Air India Ayci’s immediate task will be to bring the Air India back to profitability

Ayci’s immediate task will be to bring the Air India back to profitability That means, ahead of him lies the challenge of expanding routes, improving horrid inflight services, refurbishing airlines, and even upgrading audio-visual entertainment and other hardware on board, in addition to improving cabin crew practices. Another concern could be the resistance from the various unions of Air India, especially since the Tata group has the freedom to let go of employees hired in the past after a year.

That means, ahead of him lies the challenge of expanding routes, improving horrid inflight services, refurbishing airlines, and even upgrading audio-visual entertainment and other hardware on board, in addition to improving cabin crew practices. Another concern could be the resistance from the various unions of Air India, especially since the Tata group has the freedom to let go of employees hired in the past after a year. JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group

JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group That meant, over time, the airline raked up a debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021 and was steadily losing money on operations. In addition, Air India"s total employee count stands at around 12,500 personnel, while its wage bill for the fiscal year 2021 stood at around Rs 3,000 crore. This means a per employee cost of Rs 24 lakh. In comparison, IndiGo"s India"s largest airline operates a lean model with per employee cost at Rs 14 lakh, some 70 percent lower than Air India.

That meant, over time, the airline raked up a debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021 and was steadily losing money on operations. In addition, Air India"s total employee count stands at around 12,500 personnel, while its wage bill for the fiscal year 2021 stood at around Rs 3,000 crore. This means a per employee cost of Rs 24 lakh. In comparison, IndiGo"s India"s largest airline operates a lean model with per employee cost at Rs 14 lakh, some 70 percent lower than Air India.