Meanwhile, the woman was a bit reluctant to welcome a stranger. She had her reasons. The city had been rocked by sporadic incidents of communal riots in 1971. She asked her husband, a textile mill worker, to interact with the young salesman. After a few minutes, the trio landed in the kitchen. The woman now narrated her grievance. “Aapke chai main colour nahin aata hai [there is no colour in your tea]," the 35-year-old grumbled. Desai smiled. He lit the stove, poured water in a saucepan and boiled it for a few minutes. He then added tea leaves. The colour of the liquor changed, and the aroma filled the room. In the monsoon, he explained, the water is laced with chlorine to take care of water-borne diseases. Chlorine, the chemical engineer from Karnataka underlined, is a bleaching agent. “So boil the water for a few minutes, and then add tea," he stressed. “Ab badiya chai banega [Now you will get great tea]," he smiled.

Three years later, in January 1974, Desai was on another consumer visit in Ahmedabad. This time the complaint was regarding the brew. Meanwhile the city, billed as Manchester of India, was witnessing unrest of a different kind. It all started in December 1973 when students of an engineering college protested a 20 percent hike in hostel food fees. Over the next month, the protest spiralled across the city and state, students clashed with the police and the movement snowballed into a larger socio-political protest against high food prices, corruption and state administration.

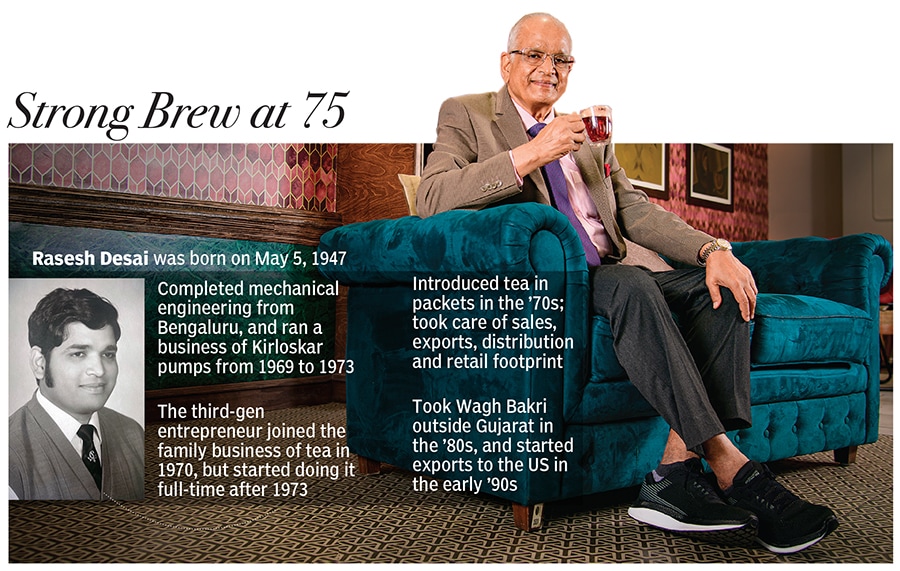

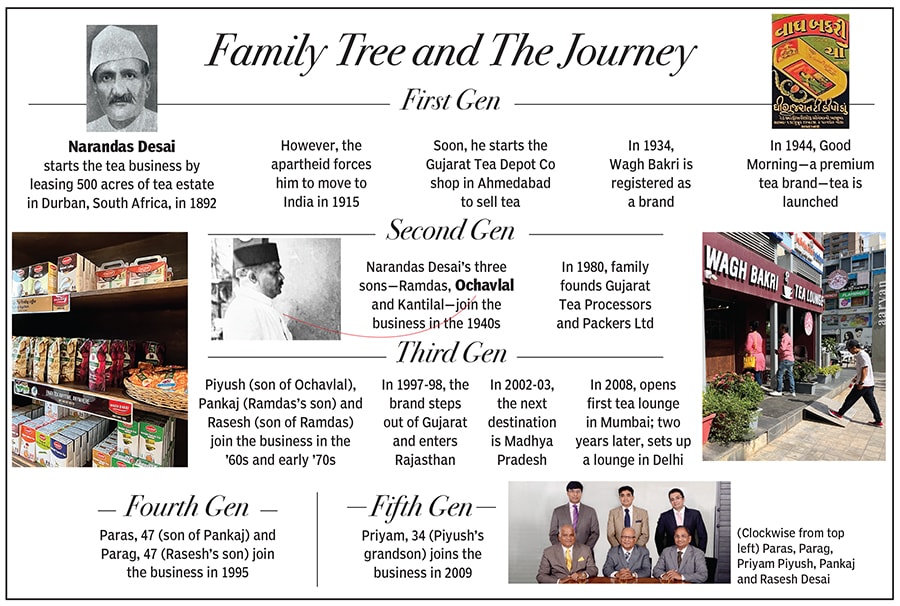

Back in the kitchen, Desai found himself in hot water. “I think your packet tea is not as good as the loose one that you have been selling since decades," was the grouse of the homemaker. It was indeed a serious perception problem for the legacy brand, which was founded by Narandas Desai, who started the tea business by leasing 500 acres of tea estate in Durban, South Africa, in 1892. Facing racial discrimination, he was forced to come back to India in 1915. His three sons—Ramdas, Ochavlal and Kantilal—joined the business in the 1940s, and Wagh Bakri remained in the loose tea business through eight retail counters that dotted parts of Ahmedabad till 1970. Now Rasesh Desai, the third-generation entrepreneur, was trying to push the family into packet tea.

Meanwhile, the political landscape of Gujarat was also undergoing a churn. Badly hit by protests across the state, the Army was called in to restore peace in January 1974. Next month, the chief minister resigned. A year later, the country was hit by an unprecedented political crisis. In June 1975, India was placed under Emergency by then prime minister Indira Gandhi. For the next 20 months, the country experienced a strong undercurrent of muzzled dissent.

![]()

Back in Gujarat, Wagh Bakri too was undergoing a silent transformation. Ironically, the trouble brewed by incessant communal riots and caste violence in the 1970s bred a conducive atmosphere for the uptick of packet tea. Due to frequent curfews in the city, shops stayed closed and consumers couldn’t buy loose tea. Consequently, packet tea gained ground. “Users realised that the quality was the same, and packs were convenient to buy and handle," recalls Desai, who started expanding the retail footprint of the brand. Small retailers, distributors and shopkeepers shunned by big companies such as Unilever were picked up to sell Wagh Bakri. “Our tea is for everyone. It’s for the rich, for the poor, for Indians and for the world," says Desai, adding that Wagh Bakri sells across 45 countries. “Unilever never took us seriously," he says with a laugh.

Meanwhile in Ahmedabad, the enterprising entrepreneur was making a serious bid to expand operations. “Throw a stone in a pond. What do you see? Ripples," he smiles, explaining the marketing strategy. “One village, one town, one city and one district at a time," underlines the entrepreneur who spent a few years selling Kirloskar pumps before joining the family business. “My family needed me back. So I joined the business," he says. The company, which registered Wagh Bakri as a brand in 1934 and rolled out premium tea under the ‘Good Morning’ brand in 1944, was in no hurry to expand its reach. “Tea is an emotion, and building emotional connect with users doesn’t happen overnight," he explains. The best cup of tea, he contends, is made when you brew it on a slow flame.

![]()

The move worked. Wagh Bakri made slow and steady progress till the early 1980s. From 1983, however, Desai found his full rhythm. The year was historic. The underdog Indian cricket team lifted the cricket World Cup in 1983. In Ahmedabad, an underdog brand felt the adrenalin rush, and the 36-year-old rejoiced in excitement. “I celebrated the victory for over a week," says Desai, who was a medium fast bowler for his college team in Bengaluru. Though famous for his lethal outswing deliveries, Desai was always stumped by his batchmates in his hostel room. “Chai waala hi sabka chai banayega [the tea man will make tea for all]," was the regular demand from his friends every morning, and Desai gladly obliged.

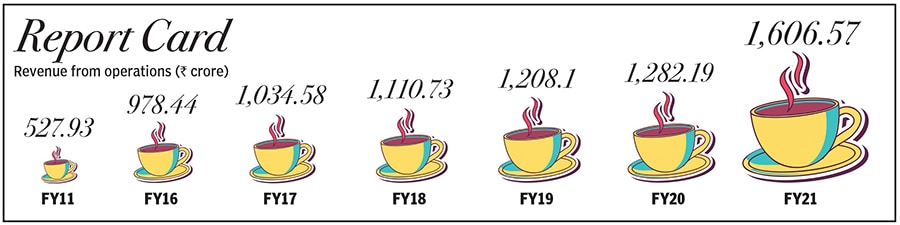

Back in the late ’80s, Wagh Bakri found itself on firm footing. In 1989, Gujarat Tea Processors and Packers Ltd (parent company of Wagh Bakri) was born, and the company posted unfaltering growth over the next decade. In FY11, the company reported an operating revenue of ₹527.93 crore, according to regulatory filings accessed through Tofler. Still no private equity, or involvement of outside capital and yes, no loss. “What is the purpose of a business if you bleed?" says Desai, who was born in May 1947. “We are a cash-rich company. So we never wanted money," stresses the 75-year-old entrepreneur, explaining the logic behind Wagh Bakri’s bootstrapped journey for over a century.

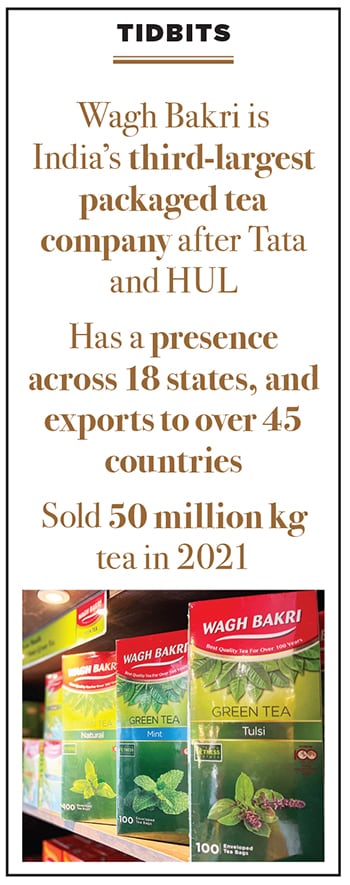

![]() Cut to 2022. Wagh Bakri has emerged as the third-largest packaged tea company in India after Tata and HUL. The Ahmedabad-based brand has a presence across 18 states, exports to over 45 countries, and sold 50 million kg of tea last year. In fact, it has shifted gears from a steady to heady growth since FY11. Look at the numbers: From ₹527.93 crore to ₹1,606.75 crore in FY21. “This fiscal, we are close to ₹2,000 crore in revenue," claims Parag Desai, son of Rasesh Desai, who passed on the baton to the next generation by encouraging them to take risks, move the brand out of the home state and carve out their own sphere of influences.

Cut to 2022. Wagh Bakri has emerged as the third-largest packaged tea company in India after Tata and HUL. The Ahmedabad-based brand has a presence across 18 states, exports to over 45 countries, and sold 50 million kg of tea last year. In fact, it has shifted gears from a steady to heady growth since FY11. Look at the numbers: From ₹527.93 crore to ₹1,606.75 crore in FY21. “This fiscal, we are close to ₹2,000 crore in revenue," claims Parag Desai, son of Rasesh Desai, who passed on the baton to the next generation by encouraging them to take risks, move the brand out of the home state and carve out their own sphere of influences.

A sharp focus on higher education and an overseas exposure was deemed crucial. Parag, the fourth generation entrepreneur, went to the US to pursue a master’s degree in marketing in 1992, and joined the business along with his cousin Paras in 1995. Over a decade and a half later, the fifth generation—Priyam—joined in 2009.

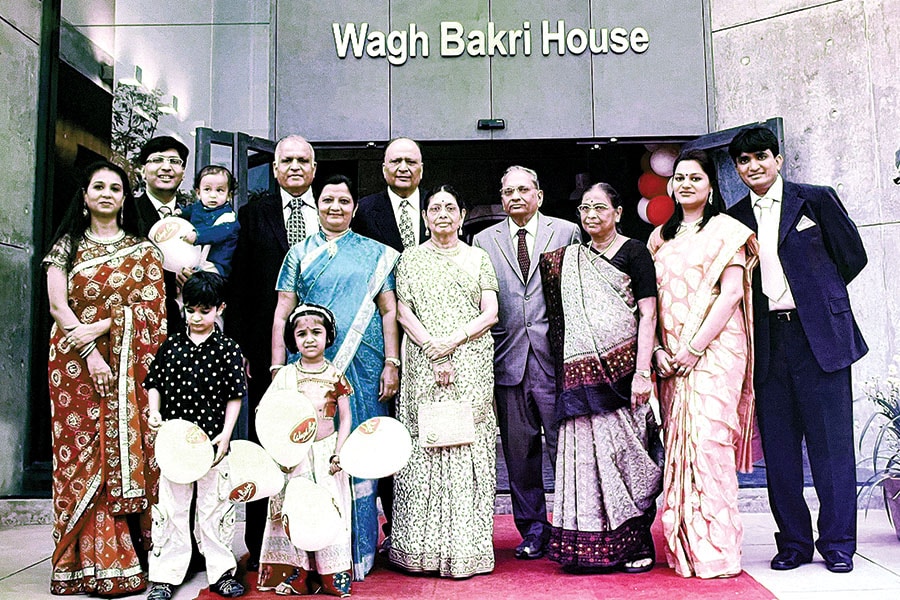

“We have 13 tea lounges, and 40 kiosks across eight cities," says the young gun who reckons that the brand has become aspirational (despite its idiosyncratic name). The business is now run by the fourth and fifth generations, while the three patriarchs from the third generation—Piyush (son of Ochavlal), Pankaj (son of Ramdas) and Rasesh (son of Ramdas)—remain the guiding lights.

Wagh Bakri, reckon social commentators and brand experts, has endured the test of time. In many ways, the journey of the tea company since 1947 and its trials and tribulations to build the business mirror the non-linear growth charted by India since Independence. “Culturally speaking, tea has had a huge role in India," contends Santosh Desai, chief executive officer of Futurebrands. “Coffee, relatively speaking, has been a footnote," he adds. Commenting on the lineage of Wagh Bakri tea, Desai underlines that the brand is more than a home-grown company. “It’s not one of the legacy brands that you remember with nostalgia. It’s a vibrant and relevant brand even today," he points out.

There is another factor that makes Wagh Bakri special. Desai explains. Historically, India has seen a bouquet of garden tea brands which existed over decades. But most of them have now either been acquired or have been absorbed into one company or have fallen by the wayside. In terms of being independent and exclusive, he lets on, Wagh Bakri would be the most significant tea brand in the country. “Tea is a great leveller," he underlines, adding that it is shared by everyone across the country, from the poorest to the richest. If there is one product that has the deepest and widest consumption and cuts across all classes, religions and regions, it’s tea. “It’s a great unifier," he says. It has a past, is very much part of the present, and will have a place in the future.

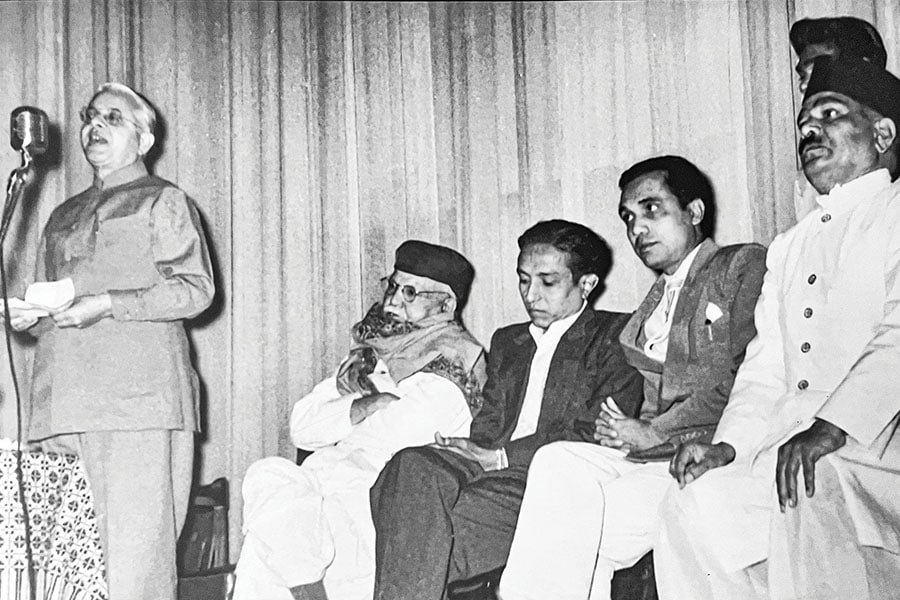

![]() Celebrating 35 years of Relief Road, Ahmedabad branch, in 1953

Celebrating 35 years of Relief Road, Ahmedabad branch, in 1953

Meanwhile, at the Wagh Bakri tea lounge in Ambawadi, over 14 km from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport in Ahmedabad, one gets to see a rich blend of the past and present.

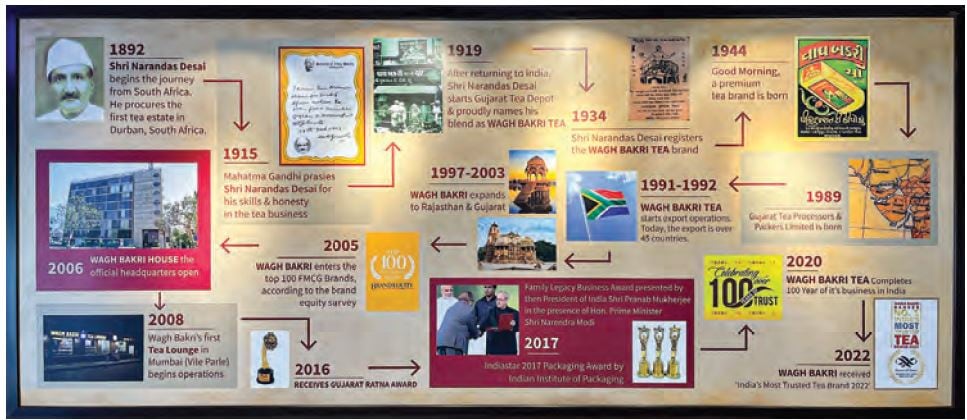

The double-storied tea lounge—the first one was opened in Mumbai in 2009—welcomes users with its tagline printed boldly on the glass door: Tea for everyone. As one enters, the first thing that catches the eye is the legacy of the company plastered on the walls. One can see the timeline, journey and milestones starting from 1892. There are words of wisdom hanging on a huge wall that binds both the floors. ‘Tea is liquid wisdom’, reads one of the posters. The adjacent one says, ‘Tea is a religion of the art of life’.

Then there is a huge slice of history, and a picture of a man whose biggest religion was humanity. A framed image of Mahatma Gandhi with Lord Mountbatten—who is sitting on a cane chair and sipping tea—can be spotted without any effort. The meeting, Desai informs, took place in April 1947, a month before he was born. He shows another visual: Narendra Modi and Barack Obama having tea at Hyderabad House in New Delhi in January 2015. As one exits the building and moves towards the corporate headquarters of Wagh Bakri—just 400 m from the lounge—one notices how the legacy tea brand has adapted itself to the needs of the present generation. ‘Karaoke available, ask for group bookings, kitty parties, celebrations, business meets etc’ reads a message as one zooms out of the premise. The adjacent building has two brands—London Yard Pizza and La Pino’s Pizza—reflecting how tea has managed to find its blend and place among millennials and Gen Z. “You have to stay relevant with the times," says the 75-year-old man who still consumes four cups of tea every day.

![]() A timeline of the company hangs on a wall of the Wagh Bakri Tea Lounge in Ahmedabad

A timeline of the company hangs on a wall of the Wagh Bakri Tea Lounge in Ahmedabad

At Wagh Bakri House—the headquarters—one sees a huge billboard advertising green tea. ‘Good health is a cup of tea’ screams the hoarding. The seven-storied building has tea imprinted all over it. ‘The warmth of tea binds everyone on one network’, is the message on the first floor. The second floor highlights the connection between tea and success: A cup of tea can lead you to success. The third one tells us that ‘nothing clears your mind like a cup of tea’.

Every floor has a message. In fact, Desai too has a message. “Coffee nahin peeni chahiye [one shouldn’t drink coffee]," says the man, as he takes a swig of masala tea which is served with a stick of lemongrass and khakra, a thin cracker widely consumed as a snack across Gujarat. If you have low blood pressure, Desai lets on, the doctor will ask you to have coffee or dark chocolate. “It’s because coffee increases your BP," he says. Interestingly, Wagh Bakri also has an instant coffee mix which is billed as ‘Wagh Bakri Cappuccino’. There is another message from the grand old man for budding entrepreneurs. “Regularly visit the market. I don’t go to the temple often, but I go to the market daily," he says.

![]() Inauguration of Wagh Bakri corporate headquarters at Ahmedabad in 2005

Inauguration of Wagh Bakri corporate headquarters at Ahmedabad in 2005

Back in the ’90s, the market outside Gujarat was a tough nut to crack. Parag explains why. “Having a name as distinct as Wagh Bakri came with its share of challenges," he says. A unique name and low brand awareness hampered wide adoption. What also acted as an impediment were the different rates of sales taxes imposed by states, a wide prevalence of fakes and the absence of logistics and infrastructure. “It was a different India back then," says Parag, who during his college days in the US would double as a sales agent over the weekends, load his car with samples of tea and try to hunt for converts in a coffee-loving nation. He did find many, and Wagh Bakri started exporting to the US in full force after liberalisation post 1991. Meanwhile in India, Parag and Paras kept playing a waiting game. “We played a Test match," says Paras. People might think, he lets on, that the brand is a laggard but the growth in the ’90s and the decade later was not easy.

Going ahead, what’s not going to be easy for the brand is maintaining its pace of growth. As they move into new territories, especially South India, they will have to come up with a different strategy and blends, says KS Narayanan, a food and beverage expert.

![]()

What brought the company here will be of little help in taking it ahead. The silver lining, though, would be its tenacity to adapt, survive and flourish. “They have done so brilliantly for decades, and there is no reason to believe that they can’t continue to do that," he says. The family, he underlines, will again need to exhibit loads of patience.

The patriarch, for his part, reckons that he has always played a long-term game. “Keep working hard, focus on quality and be patient. You do these things and you will find success," he says with a smile. What does he think about his age? Seventy-five and still going strong? “I will never retire. Tea keeps me going," smiles Desai as he asks for another piece of khakra. Seventy-five years, and it still looks like another day for him and the brand.

Cut to 2022. Wagh Bakri has emerged as the third-largest packaged tea company in India after Tata and HUL. The Ahmedabad-based brand has a presence across 18 states, exports to over 45 countries, and sold 50 million kg of tea last year. In fact, it has shifted gears from a steady to heady growth since FY11. Look at the numbers: From ₹527.93 crore to ₹1,606.75 crore in FY21. “This fiscal, we are close to ₹2,000 crore in revenue," claims Parag Desai, son of Rasesh Desai, who passed on the baton to the next generation by encouraging them to take risks, move the brand out of the home state and carve out their own sphere of influences.

Cut to 2022. Wagh Bakri has emerged as the third-largest packaged tea company in India after Tata and HUL. The Ahmedabad-based brand has a presence across 18 states, exports to over 45 countries, and sold 50 million kg of tea last year. In fact, it has shifted gears from a steady to heady growth since FY11. Look at the numbers: From ₹527.93 crore to ₹1,606.75 crore in FY21. “This fiscal, we are close to ₹2,000 crore in revenue," claims Parag Desai, son of Rasesh Desai, who passed on the baton to the next generation by encouraging them to take risks, move the brand out of the home state and carve out their own sphere of influences.