Revealed: Shashank ND's ambitious roadmap for Practo

Practo works for both the care giver and the patient. In just eight years, it has become the world's largest appointment-booking platform with over 40 million appointments annually

During a recent event in Bengaluru, someone from the crowd pointed to Shashank ND, the founder-CEO of Practo Technologies, and shouted across the room: “Practo, Practo.” It was a young man who, having caught Shashank’s attention, drew him aside to thank him for the work Practo was doing. His grandmother had been suffering for three years, he said, and no doctor had been able to diagnose her ailment. Tired of running pillar to post, they desperately searched online for doctors in Bengaluru. Finally, it was a doctor suggested by a Practo search result that solved her issues and continues to be her go-to physician. “It’s all because of you,” her grandson told Shashank. Some might call it happenstance but, for the 29-year-old entrepreneur, this was validation of his vision for the company: To simplify health care for the common man by building a connected health care platform that addresses consumer pain points.

“If someone has stomach pain, we are helping that person go to the right doctor nearby. A common man doesn’t understand medical jargon,” says Shashank. “We are trying to increase the trust between doctors, hospitals and patients by making the process transparent and eliminating the barrier of lack of information. We want to help consumers make a more informed decision.”

Practo works for both the care giver and the patient. Or, in other words, it works in the B2B (Practo Ray, an online management software for medical practitioners—doctors, hospital chains and clinics) and B2C (Practo.com, a consumer-facing search platform that connects patients with doctors in their cities, launched in 2013) segments.

In just eight years, the company—with revenues in the range of Rs 100-Rs 120 crore—has grown four times year-on-year. According to Shashank, it has become the world’s largest appointment-booking platform with over 40 million appointments annually. It is present in four other countries too—Singapore, Brazil, Indonesia and Philippines—and is exploring entering newer markets in Latin America, Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

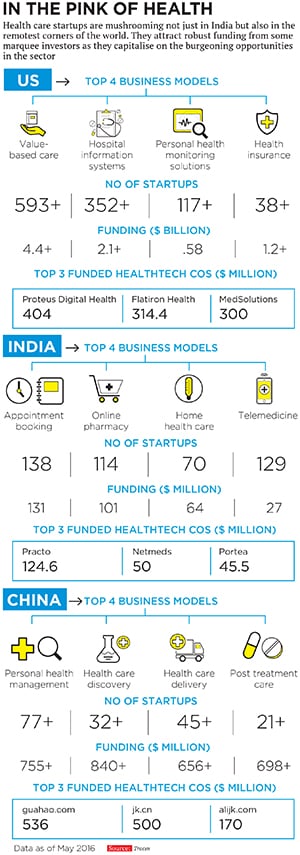

Of course, its focus is India. And the very real problem of a disorganised and limited health care industry. Consider that India spends only 4 percent of its GDP on health care, with the unorganised sector dominating. Pit that against developed countries which spend, on an average, between 10 and 12 percent the US is at 16 percent. “Players like Practo are playing an important role in the health care industry by reducing information asymmetry—information on doctors, hospitals, pricing and services,” says Ranjan Pai, chief executive and managing director, Manipal Education and Medical Group (MEMG). Concurs Meena Ganesh, co-founder and CEO, Portea Medical, a Bengaluru-based home health care service provider: “There is a place for both, players like Practo and us, in the health care space. I have a lot of respect and regard for what they [Practo] are doing. I’m sure they will be able to capitalise on the burgeoning opportunities in the marketplace.”

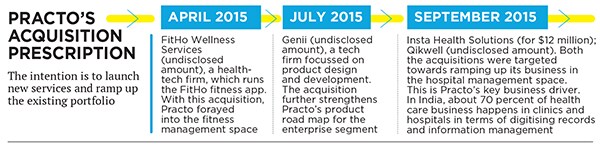

In that context, it isn’t difficult to understand why the Bengaluru-based startup is one of India’s hottest ventures in the health care space, backed by marquee global investors such as Sequoia Capital, Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings, Russian billionaire Yuri Milner’s DST Global and Google Capital. So far, Practo has raised total funding of $125 million across four rounds, the highest among health care startups in India. “Practo is building 7-8 core products in health care in an inter-connected manner. This product vision is extremely ambitious and difficult, yet many parts of the network are already visible and allow the company to grow their network very fast,” says Shailendra Singh, managing director, Sequoia Capital India Advisors. “We believe Practo will rapidly grow their multiple product lines over the next 3-5 years.”

The network growth isn’t only about new product lines, though. It is about the magnitude of reach Practo is aiming for. Shashank wants to entrench the brand in health care across the country. “All the tier II and III markets are doing very well in terms of our products. We don’t follow any model or company. Getting influenced and starting something is not sustainable in the long run,” he says. “Original ideas are always ahead in the race.”A quick glance at Shashank’s itinerary in recent times will give a sense of where Practo is headed. “Of late, I have been travelling two to three days a week within the country,” he tells Forbes India during a telephonic conversation on June 6 from Delhi. His visit to the capital included a day trip to Udaipur in Rajasthan to meet clients and survey the rural health care setups in nearby villages. “Next quarter, we are starting our services in Udaipur as part of our 100-city expansion plan this year. We are also working on some rural projects,” he says. “I met doctors and visited government health care set-ups in villages near Udaipur, trying to understand consumer pain points and how primary health care in rural India is actually panning out.” These trips are useful in understanding how health care can be made more accessible and affordable.

They are also a reminder of a bleak ground reality. The National Health Profile 2015 report prepared by the Central Bureau for Health Intelligence (CBHI) reveals that India has only 9,38,861 registered allopathic doctors, which is a meagre seven doctors per 1,000 people. According to the state-wise break up, Bihar and Maharashtra have the worst doctor to patient ratios of 1:27,790 and 1:28,391, respectively.

From a patient data perspective, the most searched specialist doctors in the country include a gastroenterologist, cardiologist, ENT specialist, paediatrician and dentist, according to a 2015 study conducted by Practo. The report was compiled from data of over 75 million searches and over 40 million appointments on its platform last year. It also highlighted that the rising rate of lifestyle diseases such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes is not just restricted to the top metros, but tier II and III cities as well.

The 100-city plan, therefore, is rooted in real demand. Currently, Practo has a presence in 50 Indian cities and is aiming to touch another 50 by the end of this year. (It also points out that about 30 percent of its traffic on the search platform is driven from outside the top six cities in India.)

Localisation, Shashank says, will be the key to penetrate deeper into such markets and reach out to a larger population. “In our practice management software, we have already started using vernacular language,” explains Shashank. “For example, when a patient gets a message from a doctor who is using our software regarding the patient’s appointment, reminder, etc, the doctor can select a language based on the city and the patient gets the message in the local language such as Kannada, Tamil, Gujarati and Marathi.”

At present, Practo offers an option of about 10 regional languages in its software product. There is also a plan to move its search interface from just English to at least three more local languages, including Hindi, by the end of 2016. This localisation extends to overseas markets as well. In Indonesia, Practo’s search (and software) interface is in the local language, Bahasa, while it is in Portuguese in Brazil.

Also, in July, Practo is looking to launch a call option for consumers in India with regard to doctor consultations, beyond the online option. Kshitij Bhotika, vice president (products), Practo, says the doctor ranking algorithm used by them is dependent on the quality. “We use feedback and various methods to understand whether the doctor is relevant to the patient or not,” she says. “We also take patient feedback on the doctors. The feedback is made public on the site. It doesn’t matter if the doctor is using our software or not.”

Practo has about 2,00,000 health care professionals (including medical doctors, ayurvedic doctors, alternative medicine experts, fitness trainers and others), of which about 1,30,000 are medical doctors. These are spread across 10,000 hospitals, over 8,000 diagnostic centres and 4,000 fitness and wellness centres.

Flanking its core offerings is the business of enterprise hardware solutions (tablets and kiosks built for managing digital records in hospitals and clinics). This was started by Practo in 2013 but has gained momentum over the last 18 months. The company claims to sell around a thousand units, including tablets and kiosks, each quarter. For the last two years, Practo has partnered with players such as Lenovo and Samsung to build these products the in-built software is Practo’s own proprietary operating system.

The demand for these products is higher in tier II and III cities as doctors buy customised tablets to manage medical records, patient appointments, feedback and registration. They are particularly useful in places with frequent power cuts and poor internet connectivity as the device can access data in offline mode and comes with a battery backup. In fact, about 40 percent of Practo’s tablet sales come from tier II cities, claims the company. Dr Kumaresan, a dermatologist based in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, has been using Practo’s management software in his clinic for over two years. “I could grasp a lot of things easily and manage billing and appointment scheduling much faster,” he tells Forbes India.

At present, the India business accounts for 90 percent of Practo’s revenue, and almost all of that is from its B2B, or software enterprise, business. Practo makes money by charging doctors, hospitals and clinics for its software management services (Practo Ray) on a subscription basis.According to industry sources, the firm, which has 2,300 employees, is valued at close to Rs 4,000 crore. “Under Practo, we have different business units and many of them are turning profitable this year. We as a company will turn profitable mid of next year [2017], including our international operations. The software business is already running in a profitable manner,” says Shashank.

This is a confident Shashank speaking, one who has earned his spurs over a period of time, by breaking a pattern.

Growing up in Bengaluru, where his father worked for the Steel Authority of India Limited and mother with Bharat Electronics Limited, Shashank had a modest middle-class upbringing. He studied at National Public School, Rajajinagar, and completed his engineering degree (information technology) from the National Institute of Technology, Surathkal, Karnataka. “I’m the only child. I have always been told to follow a set pattern in life: Schooling, followed by an engineering degree and then a job. I don’t come from a business background. My family is largely dominated by engineers. My first exposure to entrepreneurship was in college when I joined the entrepreneurship club,” says Shashank.

During his third year at college, he dabbled with a few ideas, and started Practo in the final year of his engineering in 2008. “The idea of Practo didn’t come from anywhere else. It originated from India and the problems we face,” says Shashank, who roped in batchmate Abhinav Lal to build the first version of Practo Ray while still in college. The software helped doctors upload and store medical records and prescriptions and manage billing and appointment details.

The company was bootstrapped for the initial three years, without any external capital. “For the first two years, we sold the products to doctors only on a referral basis in Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai. The business just grew organically and we hardly invested any major capital into it,” says Shashank.

Lal, 28, says Shashank’s perseverance has prevailed over testing times. “There was a time when I wasn’t very sure. I was thinking of taking up a job after completing my engineering degree,” says Lal, co-founder and CTO. He had a job offer from a global pharma-consultancy firm. But, after graduation, he decided to take the plunge. “It took ten days to convince my parents. The first year was a slow and tedious process as I was trying to create a market. But after a year, I was totally into it. I was so happy that I didn’t go home for a year.”

Shashank was convinced that the company’s product is the best marketing tool. “I have never reached out to any investor for funding. If the product doesn’t market itself then what’s the point. In 2011, Sequoia Capital noticed our venture and asked us to meet them.”

The same year, Practo raised its first seed round from the venture capital firm. “Shashank and Abhinav, from the early years, had a lot of idealism and clarity regarding building a health care platform company that would change how health care was delivered. I remember going to their annual offsite and getting goosebumps listening to the young founders describe with the utmost sincerity and a deep sense of commitment an extremely ambitious vision,” says Singh of Sequoia of the duo who are also Forbes India 30 Under 30 alumni.

This was just the beginning. In July 2012, Practo raised its series A funding of $4 million from Sequoia Capital.

Last year in February, the company raised its series B funding of $30 million from existing investor Sequoia Capital and Matrix Partners, followed by its largest round so far: $90 million in August 2015, from a clutch of investors including Tencent, Sofina, Sequoia India, Google Capital, Altimeter Capital, Matrix Partners, Sequoia Capital Global Equities and Yuri Milner.

Before Avnish Bajaj, founder and managing director, Matrix Partners, signed his first cheque for Practo, he had a personal experience with the startup. “In late 2013, I had undergone a shoulder surgery and every doctor I visited for opinions, and physiotherapists who attended to me after my surgery, was through Practo’s platform. It was clear to me that my own experience in dealing with the doctors was significantly better because of that. It was a savvy interface. That’s how we got intrigued first,” says Bajaj. “It took a while before we made our first investment.” This was in mid-2014.

Experts say Practo’s advantage over its competitors is its presence in the B2B (management software) and B2C (doctor discovery platform) space, covering both ends of the health care ecosystem.

Though it doesn’t have a close competitor in India, as Practo expands its overseas footprint, it has to contend with heavily-funded startups such as China’s Guahao and New York-based Zocdoc.

“Companies like Zocdoc and Guahao are of the size which could possibly look at India and Southeast Asia as a potential market,” says Shashank. “That’s why we are looking at expanding our operations faster and going deeper in each of the countries where we have a presence.”

To maintain its lead in a highly spirited market, Practo has to continuously invest in capital and talent to innovate in its products and services.

The key challenge in India is access to quality talent to combat the commoditisation of the software. “The differentiation is not going to come from a product. It will be intelligence—and how your product is better than any other because of its intuitive understanding and fulfilling of a consumer need,” says Lal.

To that end, last year, Practo set up an innovation lab in San Francisco’s Bay Area which looks at two key aspects: Pure technology and health care.

“We have a small team (about half a dozen people) who focus on new projects and technologies such as machine learning, artificial intelligence (AI) and big data,” says Shashank. “The quality of people is [of] mostly high-pedigree PhD background. It is a good mix of academics and engineering (software engineers and data scientists). [We see a] talent crunch in India and we want to supplement it so that knowledge exchange can happen faster.”

His immediate challenge, however, is not talent acquisition, expansion, profitability or ensuring that the service does not get commoditised: It’s finding some precious me-time for personal fitness. “I am investing my time in my own health now,” he says, even if it is an hour a day of any physical activity. After all, it is difficult to justify sub-optimal personal fitness when you are heading one of India’s leading health care startups.

First Published: Jul 04, 2016, 06:45

Subscribe Now