Beware the coming default deluge

The Covid-19 crisis is a risk that lenders never modelled for. Default rates could rise three times, says credit scoring platform CreditVidya

In two years since 2018, personal loans and credit card debt outstanding had risen at an annualised growth rate of 14 percent. The pandemic has thrown out of the window the bad loan provisioning that banks and finance companies had done prior to Covid-19

In two years since 2018, personal loans and credit card debt outstanding had risen at an annualised growth rate of 14 percent. The pandemic has thrown out of the window the bad loan provisioning that banks and finance companies had done prior to Covid-19

Image: Kuni Takahashi / Getty Images

You’re in your early 20s and you’ve just landed your first job. The first pay cheque is earmarked to upgrading the four-year-old phone. No matter that the new iPhone you have your eyes on costs as much as the pay cheque itself. After all, the cost can be split among six easy-to-pay EMIs. By the end of the first year, you’ve also taken loans for your first overseas holiday, and to renovate your parents’ home.

The bank puts you down as a model customer. Monthly salary credits point to the payments, which make up 40 percent of your salary, as being manageable. With an expected 20 percent pay increase after the first year, the loans are bound to occupy smaller share. Those who joined the company a year before you already bought their first motorcycle. That’s next on your list. Soon, you will be able to say goodbye to those cramped train rides to work.

But then Covid-19 hits, and half the team you work with is laid off. Your salary is cut by a fourth and, at 53 percent, the monthly loan payments are making it hard for you to pay rent. Your bank announces a moratorium and you opt in. Interest accrues but your account is still classified as good.

But for how long? That’s the question few have answers to.

Over the last five years, as traditional lending engines—credit to companies, home loans and auto loans—had slowed, banks and finance companies had grown their consumer book. This included quick loans to buy mobile phones and televisions, personal loans and payday loans. The last two years had also seen the emergence of loan apps, through which borrowers had to upload their income data and were instantly credited with money in their accounts. But, over the last three months, India’s consumer economy has been on pause.

According to RBI data, personal loans and credit card debt outstanding rose from Rs 19,21,142 crore in 2018 to Rs 24,90,791 crore in April 2020, an annualised growth rate of 14 percent. In the same period, total bank credit grew at 9.5 percent. Borrowers confident about their future increased the size of the leverage they took, faster than their growth in incomes. India’s household savings rate fell to a decadal low of 17.2 percent in 2017-18.

Banks and finance companies have provisioned for bad loans on account of the pandemic, but all solutions to the loans going bad are based on best guesses and data from past delinquencies. Those models for forecasting defaults are unlikely to be useful this time, according to Abhishek Agarwal, co-founder and chief executive at CreditVidya, an analytics company that works with lenders. His data paints a grim picture.

When Agarwal set up CreditVidya in 2015, it was to address a gap in the market. Lenders would decide on loans based only on credit scores that provided information on past intent of servicing loans. If someone had borrowed and successfully paid a loan they had a high chance of getting another loan even if they had little or no income. The Covid-19 crisis has demonstrated the shortcomings of this approach. “You need to match past repayment history with cash flow data and if you do that you have a far better way of modelling the probability of default,” says Agarwal. His company set about building these models.

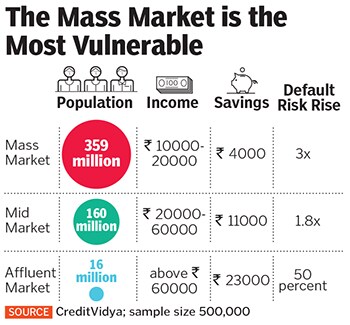

Out of the 40 million customers that CreditVidya has surveyed, it took 500,000 to understand income and consumption patterns in March and April. They allowed for the fact that there are several Indias, and divided customer segments into the affluent market (earning Rs 60,000 a month, saving Rs 23,000), mid-market (earning Rs 20,000 to Rs 60,000 a month, saving Rs 11,000) and mass market (earning Rs 10,000-20000 per month, saving Rs 4,000).

Banks and NBFCs preferred to lend to the affluent and mid-market customers, while the mass market was disproportionately (50 percent) served by fintech firms. And while the pandemic has affected each segment, it is the mass market that has borne the brunt. “What emerges from this report is that some of the impact could be more medium-term than lenders are forecasting, as jobs and incomes get disrupted, and steady-state loan delinquencies could be higher and evolve to a new baseline,” says Gautam Chhugani, director, Indian Financials at Bernstein. He also forecasts an increase in credit costs for lenders. For now, while banks and NBFCs have provisioned for defaults, they offer no guidance on what the quantum of defaults could be.

Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, the data set analysed by CreditVidya showed a 121 percent rise (note: there is no absolute number here as the data is for a cohort) in personal loans as Indians were feeling confident about the future. Most of these loans were for consumption spending, such as buying appliances, holidays, and entertainment. While personal loans rose three times in value over the last seven quarters, pay day loans increased by 11 times.

There was also the rise of a phenomenon known as ‘loan stacking’ among mass market loan seekers. This means customers would take 30- to 90-day loans at usurious (18 to 24 percent) rates. They were often self-employed—such as delivery personnel, sales personnel or temporary staff—and had no job security, but were confident of landing another job once their current one was over. They’d take new loans to pay off the previous loan, and as long as jobs were available fintech companies were happy to lend.

So, how did the pandemic affect India’s consuming class in April? Income was down 42 percent on account of significant wage cuts and furloughs. As a result, consumption was down 43 percent, both on account of lack of avenues to spend as well as the need to conserve cash. In May, there was a 15 percent rise in both incomes and consumption as green zones opened for business but the numbers are still much below pre-Covid-19 times.

Within this, the mass segment was hit the hardest. Think of it this way. When you don’t call a plumber to fix something at home, or don’t use an Uber to commute to work, incomes for the segments fall to zero overnight. The mass market saw a 56 percent fall in earnings, the mid-market 14 percent and affluent 12 percent. The mass market is also saving more—10 percent more in April.

CreditVidya’s risk assessment model points to a link between higher incomes and default rates, indicating how vulnerable the mass segment is. A person saving Rs 30,000 a month is three times less likely to default than a person saving Rs 1,000 a month. For the mass market, the 500,000-strong cohort pointed to non-performing assets (NPAs) increasing by three times, for mid-market by 1.8 times and for the affluent by 50 percent. If the pandemic is a prolonged one, the risk for the mass market increases.

This also points to a significant slowing of the consumer economy for the next year. Agarwal points out that a lot of fintech companies will see their net worth wiped out and shut shop, leaving few credit options for the mass market. As for the well-capitalised banks and NBFCs that serve the mid- and affluent markets, they have no choice but to keep trying to grow. “If bad loans increase and the loan book doesn’t grow, the NPAs as a percentage of total loans increase sharply. So for them [despite the risks] growing the book is still the only viable strategy,” he says.

First Published: Jun 19, 2020, 12:34

Subscribe Now