Dabur vs Patanjali: Veda wars

After surviving the Patanjali storm in the cities, Dabur dons an aggressive avatar to defend its rural turf. It's a battle between ayurveda based on science versus healing hinged on faith

(Left) Amit Burman Vice Chairman, Dabur and Sunil Duggal, CEO, Dabur India

(Left) Amit Burman Vice Chairman, Dabur and Sunil Duggal, CEO, Dabur India

Image: Madhu Kapparath

It took Dabur five quarters—a good 15 months—to realise that ayurveda hinged on ‘faith’ was getting the better of the one based on ‘science’. Patanjali, an ayurvedic upstart backed by maverick yoga guru Ramdev, had disrupted the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market in early 2015. The bunch that first felt the heat were the multinational giants (MNCs) led by Hindustan Unilever and Colgate, who were vilified by Ramdev as a ‘foreign evil’ exploiting the country.

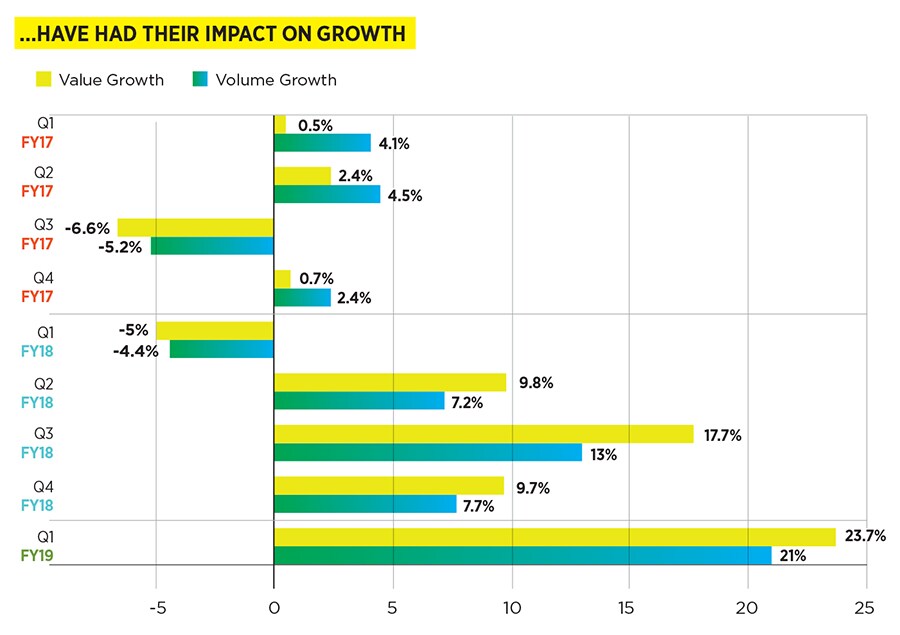

For Dabur, the fifth-largest FMCG company by revenue in India, the first vestige of a threat was in branded honey, a relatively small (worth ₹1,100 crore) category but core to the Dabur portfolio. In a first in over two decades, sales dipped by 8.50 percent in the first quarter of 2017 fiscal over the previous year’s corresponding period. For a company used to robust double digit sales growth in this category, the decline came as a bolt from the blue.

“Our competitor was selling honey at a price 30-40 percent lower than ours,” recalls Sunil Duggal, a Dabur veteran who took over as CEO in 2002. “We erred in our thinking that these disruptive forces were of short duration.”

For the next four quarters, honey sales kept sliding, slowly but surely eroding Dabur’s dominant market share of 60 percent it reached a new low of 40 percent. To make matters worse, the volume market share of Dabur’s flagship Chyawanprash brand also fell by almost 2 percent—from 58.9 percent in October-November 2015 to 57 percent during the same period in 2016.  Baba Ramdev took on MNCs with Patanjali

Baba Ramdev took on MNCs with Patanjali

Image: Getty ImagesClearly, something was wrong somewhere. In Dabur’s case it was its obsession with the bottom line. “We were concentrating more on protecting profit and had adopted a somewhat defensive posture towards disruptive competition,” Duggal recounts. This, he adds, was only encouraging the competition to get more disruptive.

For a company that traces its ayurvedic lineage way back to the early 1880s, ceding ground to a Johnnie-come-lately was a bitter pill to digest. The medicine, though, was needed. And its effect is evident today.

Three years after the Patanjali jolt, Dabur is back on song.

In the first quarter of fiscal 2019, honey sales jumped by 41.60 percent over a year ago and market share climbed to 54 percent. And Chyawanprash has hit its best value market share at 61 percent. Also, when Colgate and HUL’s Pepsodent were losing market share to Patanjali’s Dant Kanti, Dabur managed to increase toothpaste share. “We have changed our attitude. We will attack rather than defend, and protect market share and volumes rather than shield profit,” asserts Duggal, adding that there would be no let-up in the aggression.

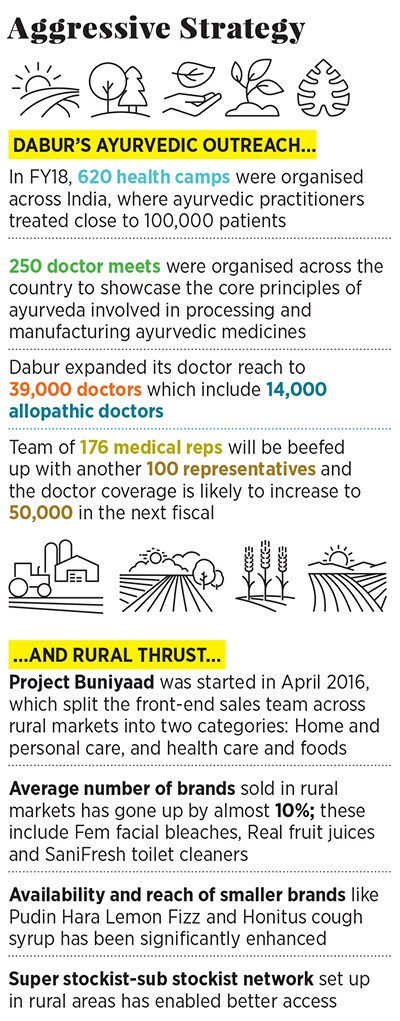

Amit Burman, vice chairman of Dabur, asserts that Dabur’s ayurveda is based on science and not faith. “We have a lineage going back 130 years, which nobody can claim,” he says. During the last fiscal, 620 health camps were organised across the country, where ayurvedic practitioners treated close to a lakh patients. Over 250 doctor meets were organised to showcase the core principles of ayurveda involved in processing and manufacturing ayurvedic medicines.The combative avatar of Dabur comes at a time when Ramdev is believed to have assembled an over-10,000-strong sales field force to fan out in rural India. As Patanjali starts losing steam in cities—bogged down by quality perceptions and spreading itself too thin into areas such as dairy and agri—the next wave of growth is likely to come from the hinterland. Dabur, which gets 46 percent of its sales from rural India, is ready for that challenge.

“We will meet fire with fire and will be far more aggressive in defending our market share than we have been in the past,” Duggal thunders. If Dabur could do it in honey, by offering a value proposition, it feels it can do it elsewhere, too.

The honey turnaround had many components: Though price was not cut, grammage was increased by 30 percent for the same price, and quality was reinforced among consumers by communicating that the product had the backing of regulatory body Food Safety and Standards Authority of India. “We knew that this (shift of consumers to Patanjali) may not last for long as our product is inherently superior,” recounts Duggal, adding that a 9 percent price cut happened after GST rates were slashed last July.

While consumers did gravitate back, what also helped Dabur were the chinks in Ramdev’s armoury. Although Patanjali aggressively expanded the market for packaged honey, due to product quality and supply chain issues, consumers lapsed out, reckons Credit Suisse in a recent report. Dabur’s differentiated marketing also did its bit in expanding sales. The company’s campaign on using honey to replace sugar for weight loss strongly resonated with health conscious consumers.

The lessons from honey were learnt quickly. Dabur now doesn’t intend to use its scale advantage to increase prices beyond a certain level.

In another departure from its core operational philosophy, Dabur took a tactical diversion by adopting a flanking strategy. The idea, explains Duggal, was to build moats around brands, in terms of better pricing or by launching flanker brands, which can be a satellite to the main brand. Take, for instance, Dabur’s blockbuster Amla hair oil. The company didn’t cut the price but launched a range of flanker brands that were lower priced. This not only acted as a moat against intrusion into the mother brand, but also ring-fenced it against future disruptions.“Just putting more feet on the street won’t work,” asserts Duggal. Reason: Rural demand for a product is different from urban it requires massive distribution infrastructure, and a robust supply chain. One needs to build the whole ecosystem to drive a rural franchise, including the portfolio of brands. “It’s very hard,” he adds.

Agree FMCG analysts. Rural, they reckon, will be a different ballgame for Patanjali. “Disruptive pricing can take you to a certain level. That’s it,” reckons Abneesh Roy, senior vice president of institutional equities at Edelweiss Securities. Pushing the same kind of products without any innovations and harping on the charisma of Ramdev in advertising won’t work, he adds.

Although the jury is still out on Patanjali’s rural gambit, early signs of impending trouble are visible.

Kherli village, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh

Egged on by the swadeshi spirit of Ramdev and Patanjali, Tej Singh opened a Patanjali store three years back. Sales, to begin with, were brisk. Dant Kanti toothpaste and cosmetics were the top-sellers, followed by biscuits, oats, vitality brand Shilajit and Swet Musli Churna—described on Patanjali’s website as ‘herbal Viagra’.

Today, however, sales are stagnating. Singh, 75, doesn’t know what went wrong. What he offers are conjectures such as more herbal and ayurvedic options available to consumers, people getting hooked to online shopping or even dissatisfaction with the products. One major issue, he identifies, is supply constraints and refusal of the company to take back expired stock.  Narottam Giri, Dabur’s rural sales promoter, visits a grocery store in Shivali village, UP, to boost toothpaste sales Dabur products on sale (right)

Narottam Giri, Dabur’s rural sales promoter, visits a grocery store in Shivali village, UP, to boost toothpaste sales Dabur products on sale (right)

Image: Madhu Kapparath

“Look at the heap of all these products,” he says, pointing to a couple of neatly-packed cartons stuffed with expired products lying on the top shelf of the store. “Patanjali doesn’t want it back and consumers won’t buy,” he rues. Nishant Bhati, Singh’s grandson, chips in. “How long can you take the losses? Even the margins have fallen,” he laments, adding that the shop has started selling cattle feed to beef up its revenue.

Patanjali declined to comment for this story.As one moves deeper into the hinterland, towards Bulandshahr district in Uttar Pradesh, the branding of Dabur Vatika hair oil or digestive pill brand Hajmola starts to fade away. The ubiquitous wall paintings or advertisements in rural India get replaced by pervasive Ramdev-branded hoardings. The difference though is that he is not seen advertising FMCG products but cow milk.

Patanjali’s strategy to enter into “endless” categories, reckon analysts, has started to take a toll. “Opening multiple fronts and spreading itself thin mean being all over the place,” contends Saurabh Jindal, analyst at Bonanza Portfolio. “You can’t dislodge Dabur in rural India if you don’t have a focussed approach.” Patanjali, Jindal adds, can’t afford to give Dabur a “second” advantage. The first was when the Haridwar-headquartered company went all guns blazing at the MNCs.

“That was advantage Dabur as it was out of Patanjali’s focus,” explains Jindal.

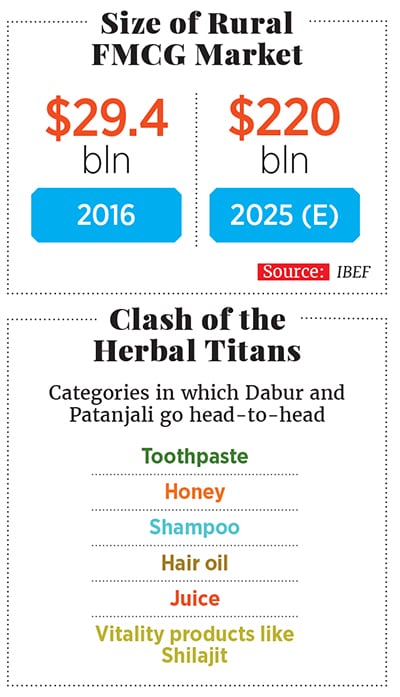

“Baba’s story has been great for us. It was never a headwind but a tailwind for Dabur,” grins Mohit Malhotra, who was appointed chief executive officer of the India business of Dabur in February. Patanjali, he points out, paved the way to mainstream ayurveda in the country. Most of the categories in which Ramdev entered now have a significant herbal or natural component, be it toothpaste, hair oil or shampoo in toothpaste, for instance, it is over a fourth, and growing rapidly. “It benefited us a big way in oral care,” he maintains, adding that the toothpaste brand that got dented because of the Patanjali push was Colgate, not Dabur.

Credit Suisse, in its latest report ‘Changing gears after a tough phase’, points out how Dabur is on track to overtake HUL to become the second largest toothpaste brand. Dabur, the report highlights, gained share over the past three years, moving to 15.5 percent volume market share. Dabur, it notes, kept growing strongly even when Patanjali was on the rise over the last three years in the naturals and ayurvedic toothpaste segment. Today it may be a different story. “Patanjali is facing major issues which will help Dabur capture more of the incremental growth going ahead,” the report maintains.  “Overall, the Baba Ramdev story has been great for us. Patanjali has impacted the business more positively than negatively.”

“Overall, the Baba Ramdev story has been great for us. Patanjali has impacted the business more positively than negatively.”

Mohit Malhotra, CEO, India Business, Dabur

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Patanjali’s flat revenue growth in fiscal 2018—revenue was reportedly over ₹10,000 crore, as against ₹10,561 crore in fiscal 2017—has made it imperative for the company to spread itself wide in rural areas as its story in urban India starts to lose steam.

In another equity research report in August titled ‘Patanjali facing headwinds’, Credit Suisse highlights how the ayurvedic disruptor is losing the plot.

While FY18 revenue was flat after growing at a 100 percent compound annual rate over the past four years, in many categories the company is facing a decline in consumer offtake. The drop, the report points out, is most profound in categories where Patanjali’s products were not differentiated, such as honey and hair care. In toothpaste and ghee, though, the company is holding on even though the incremental gain has stalled.Although Patanjali saw a massive surge in household penetration in 2017—from 27 percent to 45 percent—a lot of this was driven by non-core users who bought into the ayurvedic and naturals positioning of the brand rather than core loyalists. “We are seeing many of these consumers lapsing out as the novelty value and buzz around the brand have gone down and other companies are offering similar products,” the report maintains.

What’s more, from being the third biggest advertiser on TV during the first five months of last year, Patanjali slipped to ninth position during the same period this year, according to data by AdEx India, a division of TAM Media Research. Rivals maintained or improved their rankings. While HUL maintained its hold at the top, Procter & Gamble—the makers of Pantene shampoo—climbed one place to become the sixth biggest advertiser, taking it ahead of Patanjali. Colgate Palmolive stayed at fifth.

Patanjali’s dimming visibility on television comes at a time when Dabur has stepped on the gas to flaunt its superior ayurvedic lineage through a flurry of launches over the last year. For instance, Pudin Hara Antacid, a ready-to-use natural solution for all gastro diseases, has been launched, loaded with a clutch of herbs. Dabur Honitus Hot Sip, a ready-to-use remedy for relief from cough and cold, now has an ayurvedic coating. Other launches include Agnisandeepam Churna, an ayurvedic medicine for improving digestion, and Dadimavaleha, a digestive tonic with anar juice as the main ingredient.

MNC rivals, too, have hopped on the herbal bandwagon. While Colgate launched an economy herbal toothpaste called Cibaca Vedshakti, it also has a premium version called Swarna Vedshakti. HUL has revived Ayush and launched a series of personal care products such as shampoos and toothpaste under it.

Rural is the Road Ahead

Dabur’s Burman stresses that the focus will be on rural growth. With good reason. From $29.4 billion (₹200,000 crore) in 2016, the rural FMCG market is tipped to touch $220 billion by 2025, according to IBEF, a trust established by the department of commerce. With over 69 percent of 172 million households in the middle and lower middle group, rural India offers significant potential for FMCG companies, highlights an investor presentation by Dabur. Add to it the low rural penetration level of some of the categories—21.2 percent for toilet cleaners, 3.7 percent for honey, and fruit juice at 6.5 percent—and one gets to see why companies are sharpening their focus on rural India.

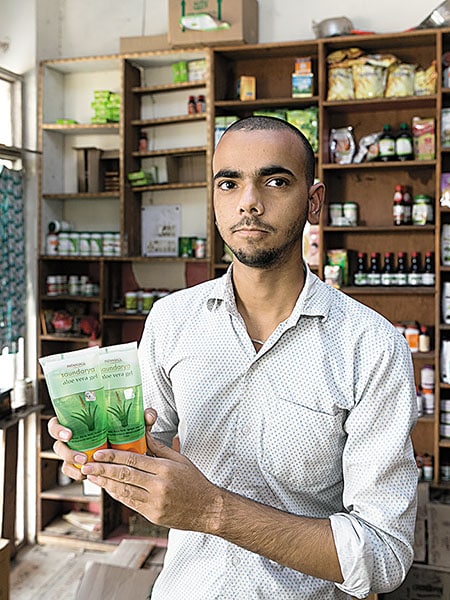

Nishant Bhati, who runs a Patanjali store in Greater Noida, is worried about the recurring losses

Image: Madhu Kapparath Dabur is fine-tuning its hinterland strategy through rural sales promoters (RSP). Narottam Giri, one of the hundreds of RSPs entrusted to deepen Dabur’s rural push under Project Buniyaad launched in April 2016, has his task cut out: Reaching out to the remotest of retailers in villages across India. Shivali is one of the villages in Bulandshahr where Giri is trying to push the sales of Dabur Red gel toothpaste.

It’s not an easy task. Shiv Kumar, owner of a small kirana store, is a crafty retailer. ‘How much would be my margin?’ he asks Giri. “Do you have any special offer for the festive season?” Giri, 34, tries to convince him to sell more of the gel toothpaste, and takes out his mobile and books more orders for Kumar. “Why don’t you pay more attention to the Dabur branding? Patanjali hoardings are everywhere,” Kumar advises Giri. “Patanjali has made its branding ubiquitous Dabur has done that with its products,” he retorts with a smile.

Patanjali and Dabur, two vedic warriors, present a contrasting picture. Though both are based on ayurveda, Dabur’s journey is marked by its reluctance to flaunt its ayurvedic parentage and work under the radar. Patanjali, on other hand, has been in your face and over the top with a mercurial promoter who believes in waging verbal war, swearing by his swadeshi credentials and opening as many battlefronts as possible.

Remember April 2016? A cocky Ramdev took a dig at his MNC rivals. “Pantene ka pant gila hone waala hai, Colgate ka gate bandh ho jayega, Unilever ka lever kharab ho jayega.” (Pantene will wet its pants, Colgate’s gate will be shut, Unilever’s lever will not work),” the yoga guru jeered, also teasing Nestlé. “Birds in Nestlé nest (logo) will fly away,” he mocked.

Two years down the line, his prophecy is yet to come out true. “Pantene’s pant is still intact, Colgate has fortified its gate with herbal coat, Unilever’s lever are working well and birds are still living happily in Nestlé’s nest,” quips Jindal of Bonanza Portfolio. What still remains unchanged, he adds, is the unpredictable nature of Patanjali. Though Dabur underestimated the impact of Patanjali to begin with, it should again not err in misjudging Patanjali’s potential in rural India. “It can’t be written off,” he sounds a word of caution.

Dabur, for its part, would be hoping that science gets the better of faith this time.

First Published: Oct 25, 2018, 12:48

Subscribe Now