ShareChat: The no-English social network

Given the dearth of vernacular content on the internet, ShareChat is trying to become India's answer to Facebook and Twitter

Ankush Sachdeva (extreme left), Bhanu Pratap Singh (centre) and Farid Ahsan, co-founders of ShareChat Image by: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaIn early 2015, an online debating platform called Opinio caught the attention of Mayank Khanduja. The app was flagged by a software internally used by venture capital firm SAIF Partners, Khanduja’s employer, to identify fast growing apps in India. Khanduja, responsible for early-stage investments at the firm, sensed an opportunity and set up a rendezvous with its founders in Mumbai.

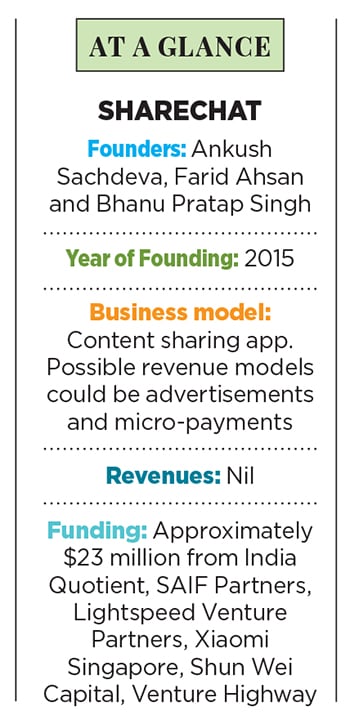

What transpired was a discovery bigger than Opinio. The creators of the app—IIT-Kanpur graduates Ankush Sachdeva, Farid Ahsan and Bhanu Pratap Singh—had started work on their next product, ShareChat, which allows users to share vernacular content—picture greetings, GIFs, text messages—on the instant messaging platform WhatsApp.

The idea struck a chord with Khanduja. It was in line with the thesis that SAIF Partners had drawn up on the scope of vernacular content businesses in India—it must cater to the non-English speaking population and thrive on user-generated content that would keep costs low and it must have a social networking component that will aid user acquisition without significant spends. ShareChat ticked both boxes and in October that year, SAIF Partners, along with India Quotient, wrote a $1.2 million cheque to Mohalla Tech Pvt Ltd, the company behind ShareChat. This was India Quotient’s second infusion into the firm.Three years on, Khanduja can take pride in having sensed ShareChat’s potential. The platform currently boasts 6 million daily active users, who use it for about half-an-hour a day on average, sharing content in 14 Indian languages. By design, ShareChat is off-limits for English content. “By eliminating English, it possibly lost the top 15 million users in the country. But that audience is already on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. It is better that as a competitor, ShareChat creates a position elsewhere,” says Anand Lunia, general partner at India Quotient.

“We invested in the firm when ShareChat had less than 1,000 daily users. What really stood out was the insight the team had about new internet users of India. They understood the kind of content users would like,” says Khanduja.

For the three founders, seasoned product builders since their college days, the insights came from experience. Before launching ShareChat, the trio had burnt their fingers on at least ten occasions, including a panorama-based real estate engine, which failed to take off. “The images were so heavy, they could not be rendered on a computer,” recalls Ahsan, chief operating officer at the Bengaluru-based firm. CEO Sachdeva avers: “Our products were technologically good, but we were not solving any real problems.”

The battle-scarred trio had to part ways in 2014—Ahsan and Singh, both 26, relocated to Mumbai after graduation, to work on an anonymous chat platform, while Sachdeva, a year younger, was completing his course in Kanpur. He would work on the product remotely and travel intermittently to Mumbai over the next year.

In those penny-pinching years, Ahsan and Singh, and later Sachdeva, would end up sleeping in the office of real estate startup GrabHouse, founded by Prateek Shukla, a friend from IIT Kanpur. To add insult to injury, their anonymous chat platform did not cut ice with investors.

Lunia felt it was not a product that Indians needed. He encouraged them to build something that will get new internet users hooked. “Hence, we thought of doing something around contextual chat rooms and came up with the idea of debating,” says Ahsan as he recalls the genesis of Opinio. “It was growing, but there were issues. A lot of users were from Europe. The debates were around nuclear disarmament and water scarcity, but we wanted [Sachin] Tendulkar vs Virat [Kohli] or [Mahendra Singh] Dhoni vs [Sourav] Ganguly.”

Then, one November afternoon in 2014, Sachdeva had his eureka moment. He came across a Facebook post that asked people to share their phone numbers if they were keen on being added to a WhatsApp group about Sachin Tendulkar. There were a staggering 50,000-odd responses.

Sachdeva sprang into action. “I quickly made a tool that could scrape a thousand phone numbers, created WhatsApp groups and left for lunch,” says Sachdeva. When he returned, each group was buzzing with hundreds of messages. More revealingly, none of the messages was in English. Sachdeva had stumbled upon the trio’s next big idea—a vernacular content sharing platform with the flavour of a social network.

This time, Lunia bought in to their idea. In February 2015, India Quotient seeded the firm with $100,000. By then, the company had retired the Opinio app.

A further eight months of iterations created ShareChat in its current form. “The good thing with the founders [of ShareChat] is, they focus on building something for the masses. While building the product, we realised that an ideal India-product would involve more sharing, and less typing,” says Lunia.

A March 2017 report by Google and KPMG suggests vernacular internet users (234 million) far outnumber English users (175 million). The report also projects local language users will grow to 536 million by 2021, as against 199 million for English. It adds that more than 90 percent of the vernacular users access chat apps and digital entertainment content. Also, rural, Indian language internet users have higher engagement. They spend approximately 328 minutes every week on chat apps, social media, online entertainment and news as against 308 minutes spent by urban users.

Investors, too, have taken note of the trend. News app Dailyhunt, self-publishing portal Pratilipi and the online video community Clip App have found backers in Chinese content company Toutiao, Nexus Venture Partners and Matrix Partners respectively.

ShareChat is reportedly in talks to snare another $70-80 million, at a valuation of approximately $400 million, though the founders refused to comment. Believed to be in the fray are a handful of Chinese strategic investors. The funds will perhaps help them sail through until the revenue counter starts ticking.

Despite its huge user base, ShareChat is yet to monetise. And it is unlikely to do so for the next one year, says Sachdeva. “There is limited value in monetising at low scale—higher ad rates come as a platform gains user scale and relevance, leading to meaningful levels of monetisation. Platforms like ShareChat have the advantage of growing predominantly through organic growth without the pressure of having to monetise too early in their lifecycle,” says Akshay Bhushan, partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners, which has invested in Mohalla Tech.

If ShareChat starts accumulating revenues through advertisements, it will be pitted against the likes of Google and Facebook, who corner a lion’s share of India’s digital ad pie. ShareChat is therefore devising ancillary revenue streams. “A bigger opportunity should be micro transactions, that is users can pay for content and services on the platform. For instance, pay for accessing horoscope, sending virtual gifts to mini-celebs or playing a game. One needs to look at China, where all the content networking businesses were driven by micro transactions,” says Khanduja. Other use cases extend to filling up forms for government exams, checking exam results and even status checks for train and flights. Adds Bhushan, “While an individual’s propensity to pay may be low, the 500 million internet users now accessible allows new kinds of business models which are driven by low ticket size, but will be multiplied through sheer scale”.

Inside ShareChat’s sparsely furnished Bengaluru office (the company shifted base to the city in 2015) spread across two floors, the buzzword is scale. About 70-odd employees are glued to their MacBooks, working on ways to make ShareChat India’s answer to global behemoths like Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

Another big job at hand is to prevent the platform from becoming an echo chamber like most social networks, replete with vitriolic messages and fake news. “At times I think, have I invested in a Frankenstein’s monster?” says Lunia.

About half the team at ShareChat is devoted to moderation and engagement with the community and content creators. ShareChat deploys a set of algorithms that takes into account about 40 signals, apart from relying on reports from the users themselves, to identify such content. Anything pornographic is detected by the algorithms and deleted even before it goes live. “We have a stringent policy for hate speech and violent content. We monitor content in a hybrid way which includes both algorithms and humans. The algorithm is trained with keywords to detect most of such content,” says Sachdeva.

Having sorted out text and images, the company is now building an exclusive video repository, all user-generated, called ShareChat Talkies. “We have about 14 studios that put exclusive content on ShareChat and we want to take that number to 50 by the end of this year. But this content needs to be something than can be created easily. We don’t want big sets, but simple things,” says Ahsan.

The hope is, someday, ShareChat will make money for its investors and itself.

First Published: Jun 07, 2018, 11:38

Subscribe Now