The truckload of rejections by VCs had one common strand: Big boys of ride sharing—Ola and Uber—had rushed into the bike taxi business just a few months after Rapido’s entry. Suddenly, all the so-called advantages of being the first player vanished. “Any investor not asking about Ola and Uber during the pitches meant that they were not serious about investing," recalls Sanka, alluding to one of the ways in which VCs expressed their rejection. The second, and the most obvious way, of refusal was to question the foolhardy of the biker gang of Sanka by trying to take on the biggies. “How will you survive against the might of Ola and Uber?" was the common question. Sanka did have an answer, but the VCs didn’t have the appetite to listen.

A few months later, in April 2016, Sanka managed to find a pillion rider in Pawan Munjal. The chairman, managing director and CEO of Hero MotoCorp, India’s biggest two-wheeler maker, invested in his personal capacity. Along with the money, came the golden nugget of business wisdom: Build for Bharat. “Tier II and III should be beautiful markets for you guys," he told Sanka and his team. But Munjal too had his share of questions: “What are you doing for women passengers? How can you change the culture of women sitting on a two-wheeler?"

![]()

Cut to March 2021. On a balmy Friday evening in Jalandhar, ‘captain’ Kanta Chauhan has completed over a dozen rides on her Honda Activa. “Initially it was quite awkward for people to see a woman riding a bike," recounts Chauhan, who has been working as a woman driver aka ‘captain’ with Rapido over the last two years. Her husband met with an accident and Chauhan opted to work part-time as a driver with Rapido. Last year, during the lockdown, she opened an eatery, which is being taken care of by her husband. Bike taxis, she lets on, are becoming popular and there is no reason why women should not be riding the boom. Rapido’s advertisement on television is making people across the country, including Punjab, aware of the concept of bike taxis. “I have a firm grip over my career, and bikes," she smiles. “Now people know Rapido, people know me," she adds.

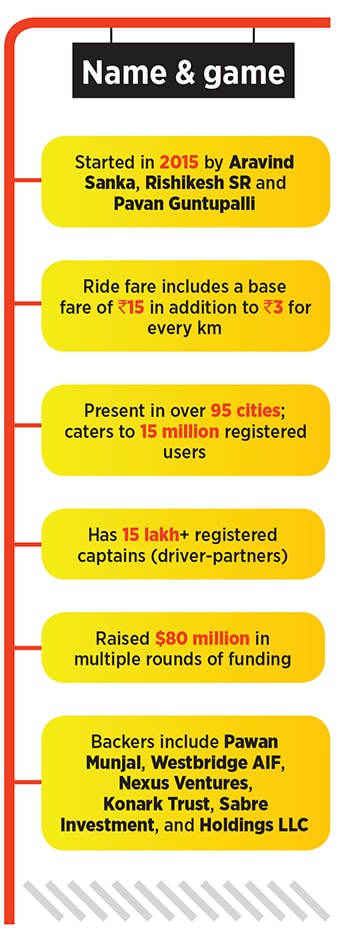

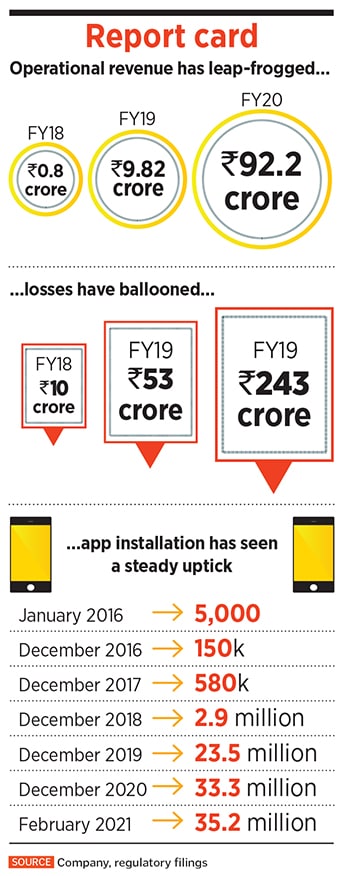

In five years, Sanka also seems to have had a firm grip over his venture. And now the VCs know Rapido, and they also know Sanka. “The same guys who rejected us now want to invest in us," he smiles. The reasons are not hard to find. First, Rapido has emerged as the largest bike taxi player in India. Second, the headroom for growth is massive in a segment which is still in its early days. Third, Rapido has managed to post decent numbers in terms of users, funding, revenue and operations: $80 million in funding, presence across 95 cities, 15 million registered users, 15 lakh driver partners, and Rs 92 crore revenue from operations in FY20. In April 2018, Sanka points out, Rapido was clocking 5,000 trips per day. “The numbers jumped to 5 lakh trips last March before the lockdown," he claims.

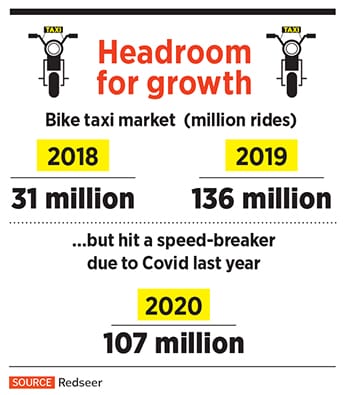

Rapido’s report card draws applause from industry watchers. The primary reason to cheer is how Rapido led the creation and expansion of a segment which was almost non-existent five years ago. In 2017, the bike taxi segment clocked 10 million rides, which jumped to 31 million the next year, and vaulted over four times to 136 million in 2019, according to consultancy RedSeer. The bike taxi market, the homegrown consulting firm pointed out in one of its reports, has had a breakout year in 2019, and is expected to grow rapidly beyond metros.

![]()

Jalandhar, ‘captain’ Kanta Chauhan with her Honda Activa in front of the dhabha run by her husband.

Ujjwal Chaudhry, associate partner at RedSeer, decodes the explosive growth of bike taxis by pointing out three factors. First is the affordability. A bike taxi is much cheaper than any four-wheeler ride sharing. Second is unavailability of cabs and autos during peak hours. Third is lower ETA (estimated time of arrival) in heavy traffic conditions and the ability to navigate smoothly as compared to cabs give bike taxis a stronger value proposition. “The fundamentals of the segment are strong, and the future looks promising once the players navigate the blip," he says, alluding to a dip in the number of rides last year—107 million—due to pandemic.

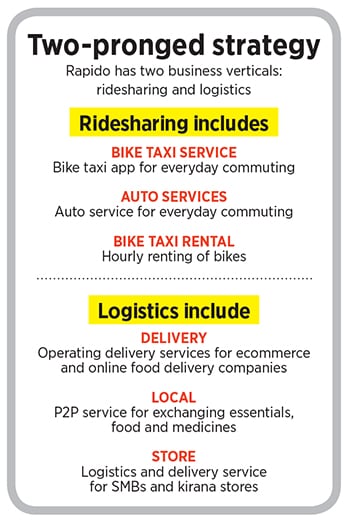

Rapido’s transformation from a one-stroke engine to a two-stroke engine over the last two years ensured that it is better placed to tide over a crisis. From primarily being a bike taxi venture, Rapido has added multiple revenue layers to its business such as auto services, bike rentals, logistics and food delivery (see box).

![]()

Bike taxis, reckons Shivathilak Tallam, senior investment associate at Unitus Ventures, make more sense for hyperlocal usages. “They work well for first and last-mile connectivity and as feeder services for mass transit," he says. Given the ticket sizes and convenience offered, bike taxis can become the mainstay for the growing middle class and will work especially well for short distances. Moreover, given the population density of the country and the road infrastructure, Tallam points out, bike taxis make more sense for travel in densely populated areas.

Back in 2016, two things made sense to Sanka. First, not to take the big boys—Ola and Uber—head-on. Second, find a way to grapple with fear. In the early days, he points out, the fear was about an existential crisis. “Questions like whether we will stay or not loomed large," he recounts. The fear was valid. Rapido was competing with Ola and Uber institutional investors shied away from backing the David and Sanka was not sure if there would be enough takers for the alien concept of bike sharing in the early days. Rapido’s founding team was also aware of another aspect of the enormity of the problem. “If I"m just taking the market from Ola and Uber, then I"m not creating a ride sharing market," Sanka reasoned with his team. Though such an approach did merit a chance, the flip side was too costly for Sanka to ignore: Bleeding operationally. “Their (Ola and Uber) one-hour burn was like my yearly burn," he says. So Rapido stood no chance to beat the big boys by following the rules set by them.

![]()

Sanka changed the terms of the fight. Burning money was not an option because there was no money. “We played to our strength," he recalls, alluding to the move to not spread wide. Started in Bengaluru, Rapido remained confined to one more city—Gurugram—for close to two years. The idea was not only for the storm to die out but also fine-tune the dynamics of the business by understanding the unit economics. “It’s a low margin, low-ticket and high volume business," he says. The third city for Rapido—Mysuru—turned out to be the turning point for the venture. “Within six months, our ride sharing became bigger than any cab player," he says. Business opportunity in Bharat—what Munjal talked about in 2016—was playing out in front of Rapido founders. The gold lied in the dusty country roads and clogged smaller towns. “For over 40 percent of the users in Tier II and III cities, Rapido happens to be their first ride-sharing apps," claims Sanka.

Keeping a razor-sharp focus, point out analysts, helped Rapido navigate the choppy waters. “At times, focus trumps size," says Ashok Shastry, co-founder of DriveU, an on-demand driver aggregator which has a collaboration with Rapido. While the Big Boys were duking it out, Rapido was able to prove a product-market fit, raise a war chest of its own (however small that be), and quickly expand into Tier II cities. While having a massive war chest does kill competition, Ola and Uber had their own big fight apart from multiple ventures that the duo was taking a stab at such as food delivery. Shastry points out two more factors that helped Rapido gain in popularity. First, it conserved cash by remaining slow and steady, and sticking to a few cities. Second, it tried to tackle the issue of ‘trust’ from day one. “Trust is always a factor when it comes to sharing a vehicle with an unknown person," he says. In Rapido’s case, it had to build even more trust because a person is sitting on the back of a two-wheeler, which is more dangerous than a car. It solved this issue by providing trip insurance to the pillion at Re1. “It was a big challenge to overcome," he says.

![]()

Sanka, for his part, reckons that a bigger challenge waiting to be surmounted is awareness. “Trust does play a role, but only when there is awareness about a product or concept," he says. But what about a bloated bottom line? The loss in FY20 stood at Rs243 crore as against Rs53 crore during the previous fiscal. Sanka claims that Rapido has considerably brought down operational losses to almost 10 percent. The reasons for huge loses, he explains, is not hard to guess: Investment in team, technology, infrastructure, and the pandemic. Our financial performance, Sanka stresses, is promising and the company is looking at introducing additional revenue streams to further bring down the losses.

Analysts are not worried about the losses either. Bike taxi is a new concept and Rapido has been marketing heavily to acquire users, says Tallam of Unitus Ventures. “It also needs to incentivise supply-side drivers to ensure they are on the platform," he says, adding that these early spends to create adoption on supply and demand make up a large part of the spending. “This will continue for a while," he says. The category, he explains, mostly banks on user behaviour change to drive profitability. Buying behaviour change is expensive, and if Rapido is able to create repeat usage behaviour, then the lifetime value of the user will eventually drive unit economics into the positive territory. “However, this isn"t an easy feat to pull off," he adds.

Meanwhile, Sanka is confident of rapid growth. Creating a new habit and a new culture of sitting on a two-wheeler behind a stranger takes time. “Educating people about the concept is the key," he says. Two things, he points out, are needed to overcome the challenges: Perseverance and focus. “If we can execute in a similar way for the next two years, we should be larger than what we are," he says.